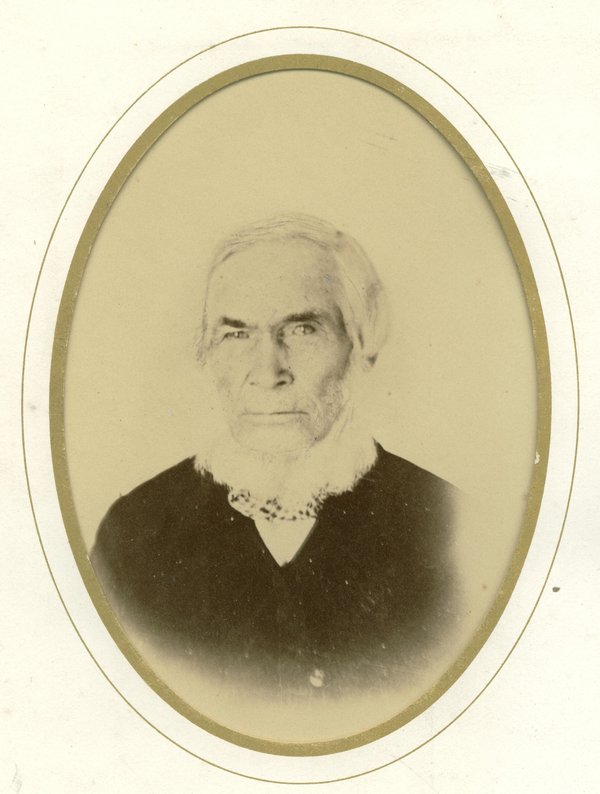

John Byington, the first president of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, struggled with envy and depression, prompting church co-founder Ellen G. White to publicly rebuke him in a letter that only increased his bitterness.

But Byington ultimately embraced White’s advice. He went on to be elected as church president four years later left a lasting church legacy, offering Adventists today a reminder about the wisdom of following godly counsel.

"John Byington had a far-reaching thrust into the future,” said Chantal Klingbeil, associate director of the Ellen G. White Estate. ”This wouldn't have happened had he not heeded Ellen White's counsel.”

White’s advice, published in books known collectively as the Spirit of Prophecy, was not only written for Byington but for anyone seeking a closer relationship with Jesus, Klingbeil said. In addition, her writings have grown the Adventist Church into the only global denomination that has emerged from the Millerite movement in the 1840s, she said.

“Many of these other churches have crumbled, but the Seventh-day Adventist Church has continued from strength to strength,” she said. “That unifying force has been the Spirit of Prophecy. Without prophetic guidance, we as a church would not have lasted."

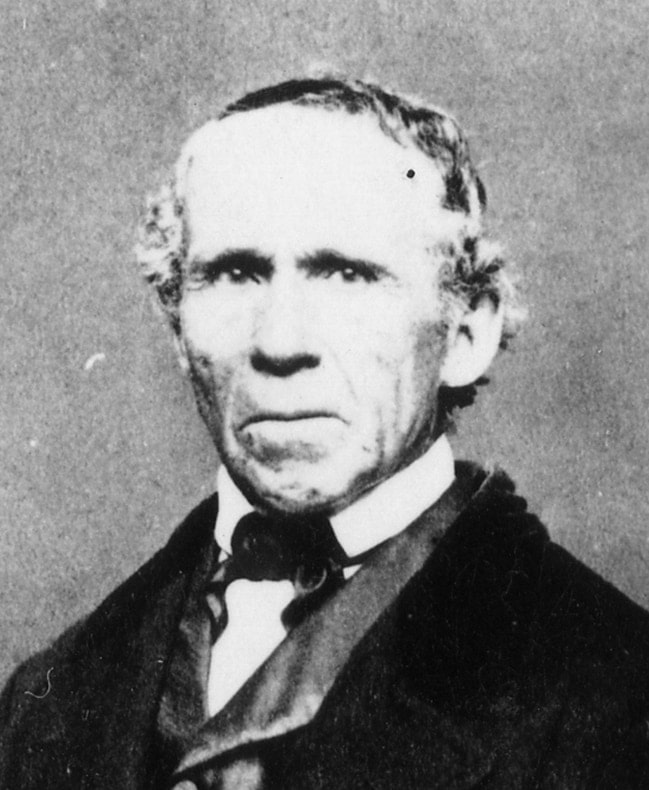

Byington, born in 1798 to a father who served as a soldier in the American Revolutionary War, had a stubborn streak that got him into trouble sometimes in his work as a New York farmer and itinerant Methodist preacher with staunch abolitionist views. He was not afraid to share those views, a fact that was reflected in the names of two of his sons, William Wilberforce and Luther Lee. When the Methodist Episcopal Church refused to support abolitionism, Byington joined the newly formed Wesleyan Methodist Church, founded in upstate New York in 1843.

Byington accepted the Sabbath in 1852 and immediately placed the same fervor and determination into his new convictions as he had in his prior association with the Methodist church.

Six years later, he readily accepted an invitation from James and Ellen White to move with his family from their farm in Bucks Bridge, New York, to minister to a growing group of Adventists in Battle Creek, Michigan.

Byington bought three adjacent farms outside Battle Creek and left his family to care for them as he traveled across Michigan to share the Sabbath message. But the move to Michigan, and the sacrifice it required, did not prove as remunerative as the 60-year-old Byington had hoped, and he grew depressed and disillusioned with his new faith.

“You had an income there that you do not have where you are,” Ellen White wrote in a letter to him.

Furthering his state of dissatisfaction was the perceived partiality of the Whites toward Joseph Bates, who co-founded the Adventist Church with the Whites. The Bates family received a house, paid for by a fundraising drive of believers organized by the Whites, but he got nothing as he struggled to pay his bills.

“He thought to support himself with the farms while he preached throughout Michigan,” said Sylvia Byington Nosworthy, the great-great-granddaughter of John Byington and an English professor at Walla Walla University. “If he was not to work his farm, then how was he to be provided for?”

She noted that her great-great-grandfather relied on farming to provide both for his family and to finance his itinerant preaching.

In his discontentment, Byington stopped preaching.

James and Ellen White visited the Byingtons, and they offered intercessory prayer for the family’s gravely ill daughter, Martha. But the April 1859 meeting disappointed Ellen White. She wrote in her diary that Byington “appeared cold and unfeeling.”

“His heart is too much wrapped up in the things of this world,” she wrote.

Two months later, with Byington sinking further into doubt and despair, White wrote him a letter in which she said God was “displeased” with him.

“You love this world, and your heart is altogether too much wrapped up in the things you possess,” she said in the letter, part of which was published in the book Manuscript Releases, Vol. 5. “There must be an entire change in you in these things.”

The advice was not well received, and Byington grew more unhappy with the publication of his struggles.He was depressed and had withdrawn from ministry. He hadn’t preached for about a year.

Despite his initial anger, Byington did humble himself and heed the admonition the same month that he received the letter. A complete change occurred in him. After White met him again a month later, she noted: “He looked happier than I had seen him for months. Says after a week he is going out to labor for the Lord, and expects to be absent six months. Thank the Lord for this.”

Years later, Byington gave an indication to what had happened when he wrote, “I have felt my sins were many; have asked and found mercy of the Savior, and would declare His loving-kindness to all.”

Byington returned to his ministry of visiting various church members across Michigan.

Four years later, in 1863, he was elected as the church’s first president at the organization of the General Conference in Battle Creek, Michigan. He was voted in after James White declined the position, and he held two one-year terms.

Unlike Byington, several early Adventists refused to follow White’s advice, including Stephen Smith, who infamously threw a letter from White in a trunk and only opened it 28 years later. He acknowledged after reading the letter as an elderly man in 1885 that his life would have been much better if he had opened it and heeded its advice immediately.

John Harvey Kellogg, the medical doctor and inventor of corn flakes, ignored White’s counsel not to rebuild the Battle Creek Sanitarium after a fire in 1902. Kellogg fell away from the Adventist Church and later was disfellowshiped for beliefs that could not be reconciled with Adventism.

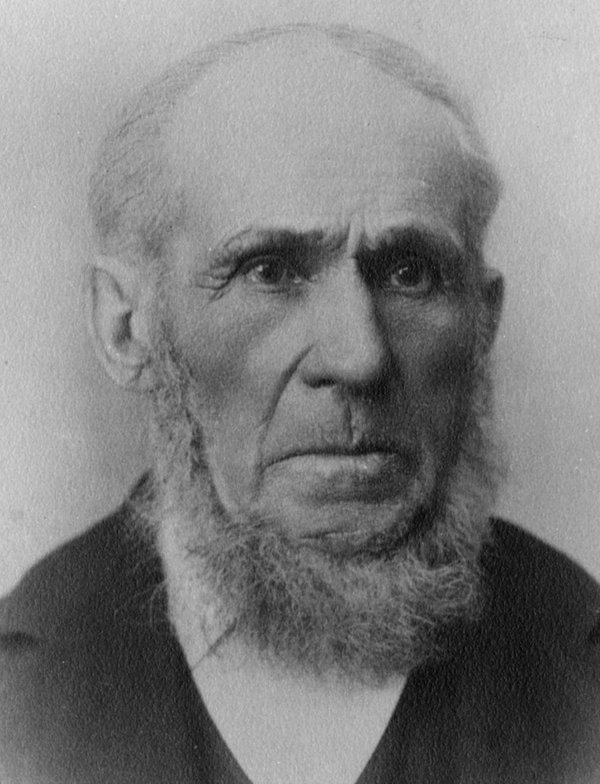

Byington, meanwhile, labored intensely as president to unify the unorganized Adventist Church.

“John Byington’s age and experience brought that surety to the new church,” said Nosworthy, who keeps in touch with her family past by conducting summer tours at the Historic Adventist Village in Battle Creek. “What he had gained in the separation of the Wesleyan Methodists from the Methodist church now was useful in the organization of another new denomination.”

His presidency focused on bringing a spirit of unity to disconnected members. He preached, held Sabbath schools, and encouraged members in the truth.

Byington, fondly referred to by church members as “father,” left a continuing legacy that includes the practice of conscientious objection and the church's organizational structure.

But his greatest legacy was his willingness to stand for the truth and heed correction from White, said Howard Krug, a specialist in early Adventist history who teaches at a high school in Rochester, New York.

“He took it to heart and ministered for the next 15 years, traveling and working for the Lord, spreading the three angels’ message across Michigan," Krug said.

Byington returned to his farm after James White accepted the presidency in an 1865 election.

He and his wife, Catherine, maintained the farm well into their 80s. He also continued his travels, preaching the gospel and encouraging Adventist believers.

He died in 1887 at the age of 89.

Ellen White’s counsel left an indelible mark on the last 30 years of Byington’s life and ministry, perhaps best expressed in a hope-filled message that he once sent a group of believers whom he wished he could meet in person.

“Tell, O tell them,” he wrote, “to leave the world and come to their Savior!”