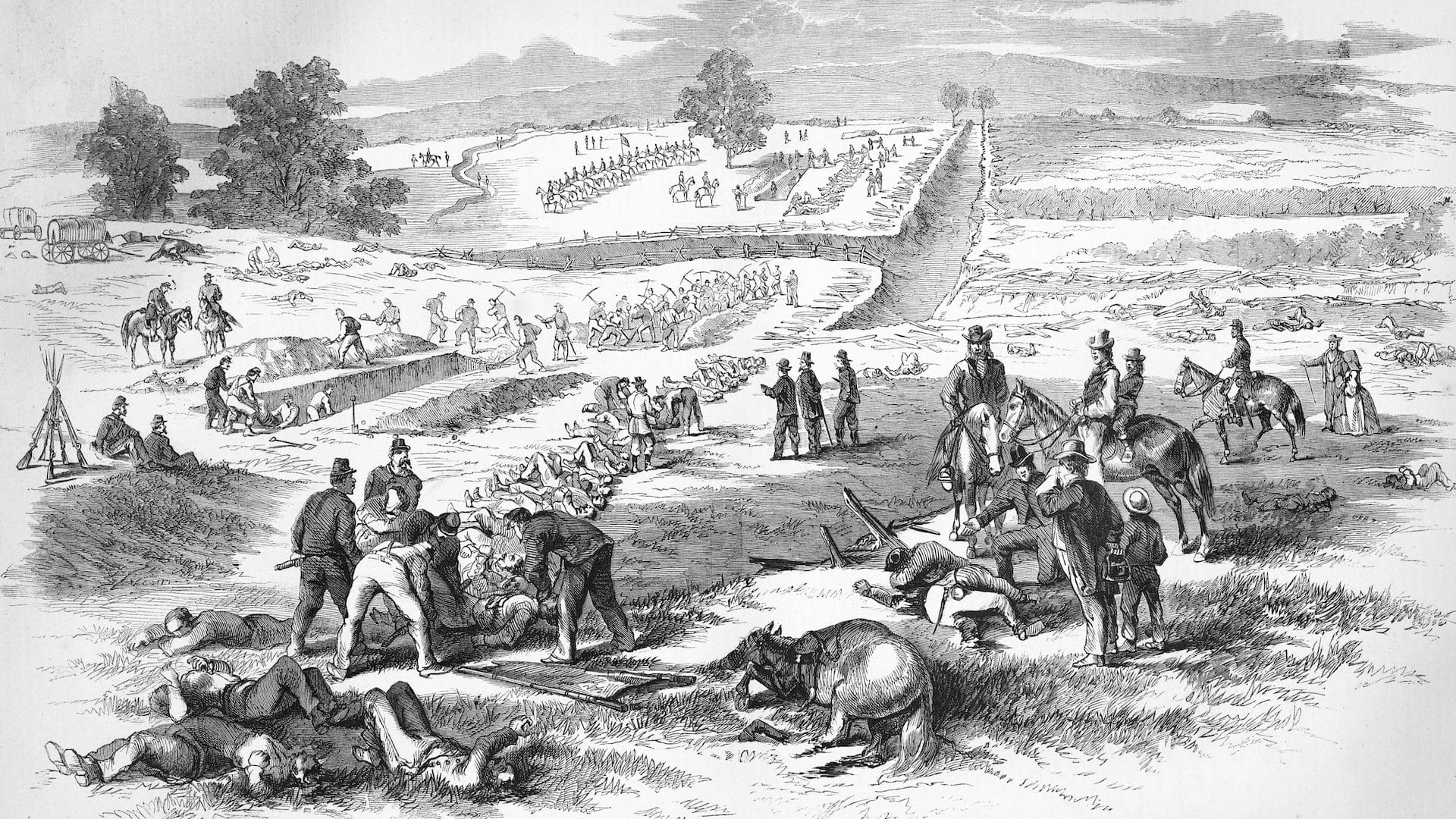

The commitment that inspired Joel Klimkewicz, a Seventh-day Adventist incarcerated by the United States Marine Corps for his refusal in the twenty-first century to engage in killing for the sake of principle,1 has deep roots in the early Adventism of the nineteenth century. Questions of war, peace, and violence became urgent, real-life concerns for Seventh-day Adventists from the moment they first organized as a denomination. When the first conference (Michigan) organized in October 1861, the American Civil War had been flaring for just six months. The first General Conference Session began on May 20, 1863, two weeks after the stunning Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, and about six weeks before the great turning point marked by Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg.

At the very time they were completing a tumultuous process of sorting out who they were as a movement, the nation’s “fiery crisis” confronted Adventists with the question of what their radical faith meant for the moral dilemma of war. Resolving that dilemma wasn’t easy or simple, any more than it is for Adventists today.

Three powerful forces tugged at the hearts and minds of the pioneer Adventists, at times twisting them this way and that, as they struggled to find direction concerning the issues the war imposed on them. The first of these forces was their fervent dedication to following the teachings of Scripture all the way. This is what their movement was all about— to be a people who upheld “the commandments of God and the faith of Jesus” in a time when compromise was all around.

A second influence was pragmatic concern for the survival of their fledgling movement. With the organized church just beginning to take life, Adventists did not want to see it become a casualty of wartime intolerance or deprivation, with its mission left unfulfilled.

The third force was their passionate opposition to slavery. The first Seventh-day Adventists were not at all neutral or indifferent about the issue at the heart of the war.

Amid the interplay of these sometimes countervailing forces and the momentous events happening around them, Adventists found their way to a corporate stand for nonviolence and peacemaking. Here is how it happened.

The pioneers of Adventism would probably be something of an embarrassment to those of us who feel comfortable in the respectable mainstream of Western society. The radical reform movements centered in New England and upstate New York in the 1830s and 1840s constituted their spiritual and moral breeding ground. More moderate reformers regarded these radicals, who brooked no compromise with such entrenched evils in American society as slavery and the liquor traffic, as dangerous extremists. One powerful spokesperson for abolitionism, William Lloyd Garrison, was reviled across the spectrum of conventional politics in the 1830s, and barely escaped lynching at the hands of a Boston mob.2

Many early Adventists were also influenced by the Christian nonresistance movement that Garrison led. They regarded scripturally grounded pacifism as part of that radical faith that set them apart from the large majority of Americans. Christian nonresistance had been espoused by the Millerite Adventist reformer Joshua V. Himes, as well as William Miller himself (according to Garrison). That commitment was also apparent in the post-1844 group that formed the nucleus of the emerging Seventh-day Adventist Church. It found occasional expression in the early publications of the Sabbathkeeping Adventists during the late 1840s and 1850s.3

To them, the scriptural basis for this stance seemed quite clear. Just as they took literally what the fourth commandment said about the seventh day being the “Sabbath of the Lord thy God,” they believed that the sixth commandment, “Thou shalt not kill,” prohibited the taking of life. They also believed Jesus meant what He said in telling His followers to “love your enemies.” Participation in military combat seemed a clear and simple violation of the sixth commandment and the teachings of Christ.

These early Adventists fully recognized that Scripture also instructs believers to render due honor and subordination to civil authority. This teaching took on particular importance for them in the early 1860s as they set up their fragile new church organization in a society wracked by a great civil war. As a very small group with dissenting convictions that set them sharply apart from the general society, they could very easily become targets of repression in a time of national crisis. In that setting, it was especially important for the church to show that its radical message did not promote violent rebellion against civil authority.

For the pioneer Seventh-day Adventists who had not spread beyond the North at that point, the relevant civil authorities were those of the Union and those states loyal to it. Adventists were on the lookout for ways to counter suspicions that might be aroused by their pointed preaching about the sins of the Protestant majority culture in America and ultimate divine judgment upon it. They wanted to demonstrate that their message was not one of disloyalty to the Union, and most definitely not one of sympathy for the Confederate rebellion.

Finding ways to accomplish this without watering down the “third angel’s message” was not easy to do, and Adventists’ deep and outspoken opposition to slavery, the third influence we are tracking, further sharpened the dilemma.

Throughout the 1850s—and in the pages of this magazine—abolitionist protest was a major theme in the Adventist warning message to America. In this era the leading Protestant denominations collectively held an informal, yet very real, dominance in American culture. Though there had been considerable debate and even division in the churches over slavery, most of the major Northern churches avoided strong pronouncements about slavery, earning them heated criticism in the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald for their tolerance of a racist system of human bondage.

Early Seventh-day Adventists proclaimed a striking word of judgment about slavery to America’s Protestant “empire,” addressing both the Southern embrace of the institution and Northern complicity with it. “God is punishing this nation for the high crime of slavery,” Ellen White wrote in August 1861. “He has the destiny of the nation in His hands. He will punish the South for the sin of slavery, and the North for so long suffering its overreaching and overbearing influence.”4 The church’s first journal, published by her husband, joined in the abolitionist criticism of President Lincoln for failing to make emancipation of the slaves a goal of the war. Only in late 1862 did the president announce that the war was being fought to free millions of enslaved Americans.5

The dilemma for the Adventists of the 1860s was multifaceted: if they resisted military service out of faithfulness to Scripture, they risked accusations of disloyalty, a severe government crackdown on their movement just as it was getting off the ground, and indirectly abetting the slave system they so fiercely opposed. Joining freely in armed combat, though, would make a mockery of their claim to be a remnant faithful to “the commandments of God and faith of Jesus.” Their witness to the fourth commandment as well as the sixth would be compromised. Such a course might reduce conflict with the surrounding society, but at the price of compromising the church’s prophetic message and mission.

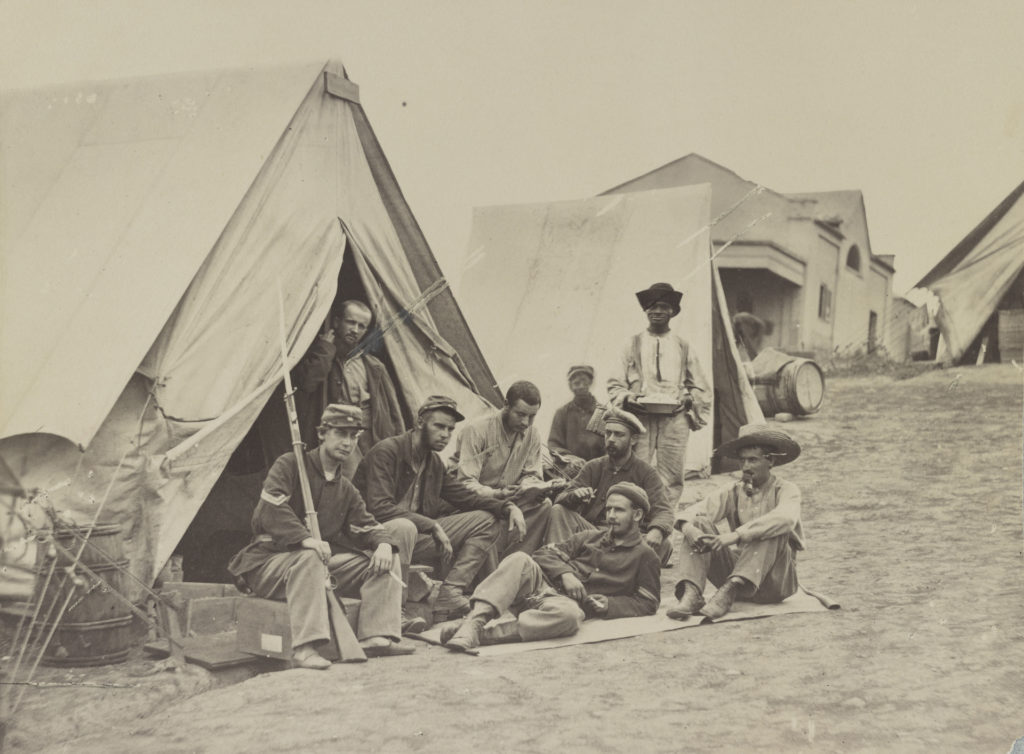

How did believers work through this challenge? The fact that no general draft was enacted in the early stages of the war gave them a little breathing room. At the outset of the war, President Lincoln called upon the states to raise volunteer armies to fight the Confederate “insurrection.” The president’s statement created some pressure for Adventists, however, because states and local communities were required to meet quotas for bonuses to pay the volunteers. James White and John P. Kellogg participated on a Battle Creek committee for this purpose.6 But no Adventist or other objector to military combat needed to volunteer.

The much-discussed possibility of a draft still loomed over them, however. James White, the church’s foremost organizer, addressed the issue with a pragmatic line of thought in a Review editorial of August 1862 entitled “The Nation.” White reasoned that if Adventists were drafted, they would be well advised to submit, and the government would assume responsibility for any violations of the law of God that the drafted individual would commit.7

White’s editorial sparked vigorous, extended debate in the pages of the Review, and his position was attacked from all sides. Some believers called for Adventist participation in the Union’s “crusade against traitors”—one even fantasizing about an armed regiment of Sabbathkeepers that would “strike this rebellion a staggering blow.” Others advocated thoroughgoing pacifism. Henry Carver, for example, maintained “that under no circumstances was it justifiable in a follower of the Lamb to use carnal weapons to take the lives of his fellow men.” Adventists in Iowa petitioned the state legislature for recognition as a pacifist church. In fact, it was their eagerness to declare their intention to resist a draft, even while it was not yet certain that it would be enacted, that had prompted James White to editorialize on the issue in the first place.

In responding to criticisms of his editorial, White clarified two crucial points about his position that his critics tended to overlook: (1) he would never encourage a Sabbathkeeper to volunteer for service in the army; (2) if believers were drafted they should do their best to obtain Sabbath privileges and recognition as noncombatants. Only if such efforts failed would moral culpability fall upon the government.8

Then, just before the federal draft was instituted in March 1863, a testimony from Ellen White deftly set forth a position that avoided reckless posturing in any direction while also asserting a principled stand on the commandments of God. The prophet rebuked both the ill-considered bravado about resistance to the anticipated draft expressed by the Iowans zealous for a defiant pacifism, as well as the militant impulse to take up arms for the Union’s righteous cause. Adventists should not court martyrdom with provocative pronouncements, she cautioned. Yet it remained the case that “God’s people . . . cannot engage in this perplexing war, for it is opposed to every principle of their faith. In the army they cannot obey the truth and at the same time obey the requirements of their officers.”9

The guidance from Ellen White drew together and addressed various elements from the conflicting influences that both motivated and unsettled Adventists in this time of crisis. They would take their stand for divine law, which meant a refusal to engage in military combat. Yet they should be prudent, avoiding rash moves that would unnecessarily stir antagonism from the government. And, again for practical reasons, but also because of their moral opposition to slavery, they would take every opportunity to show that they were not disloyal to the Union and were in fact advocates of the highest ideals that their government espoused.

The federal draft law enacted in March 1863 heightened the pressure on Adventists, but still provided a means for avoiding direct confrontation with the authorities, albeit a costly one. The law stipulated that a drafted individual could fulfill his obligation by either purchasing an exemption or providing a substitute. The hefty $300 commutation fee placed a financial strain on the church as it tried to raise the necessary funds for those who could not afford it.

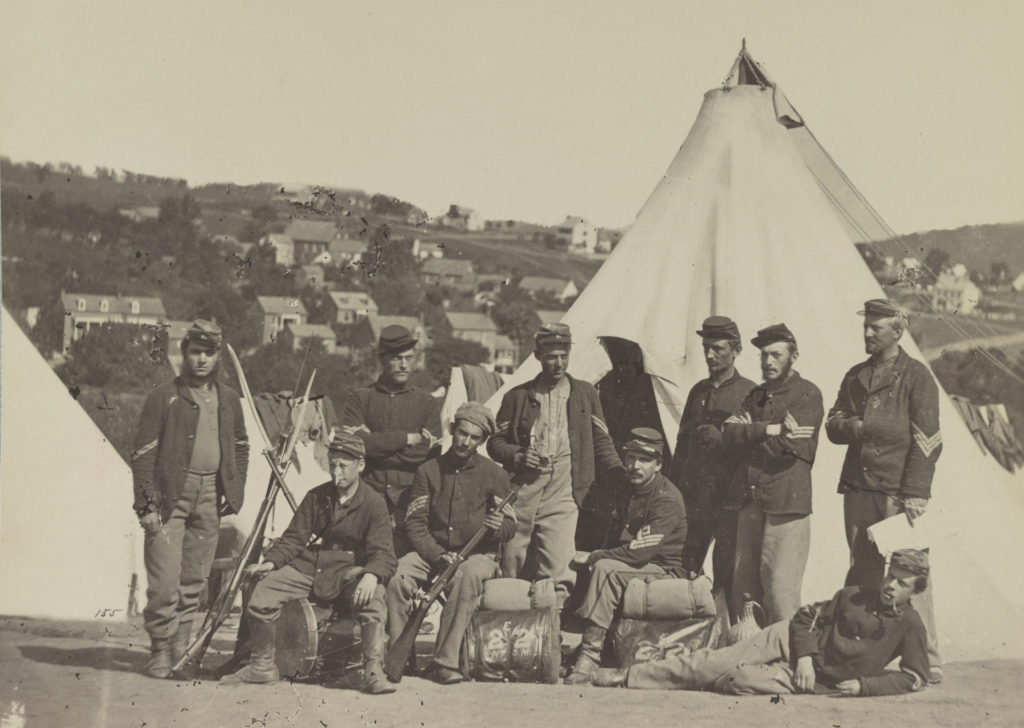

In July 1864 Congress restricted these options to conscientious objectors who were members of a recognized pacifist church. For Adventists, the decisive moment had come, and the young church’s leaders moved swiftly. John N. Andrews was authorized by the General Conference Committee to go to Washington and seek governmental recognition for the noncombatant position held by Seventh-day Adventists. “May it be favorable for those who have enlisted to serve under the Prince of Peace,” declared James White in reporting Andrews’ mission.10

Andrews’ petition, presented to James B. Fry, the provost marshal general, described Seventh-day Adventists as “a people unanimously loyal and antislavery, who because of their views of the ten commandments and of the teaching of the New Testament cannot engage in bloodshed.” General Fry responded favorably to the petition, and issued an exemption that gave Adventists the option of either accepting assignment to hospital duty or care of freedmen or paying the $300 commutation fee.11

The success of their petition may obscure the fact that by thus bringing their nonconformity into the open, the little-known group took the risk of their cause being rejected. Moreover, even with high-level governmental recognition achieved, individual Adventist draftees still suffered denials, temporary imprisonment, threats of court-martial, and other forms of harassment when attempting to claim their right to alternative duty, owing to lack of understanding among officers about the provost marshal’s provision, prejudice against noncombatants, and poor communication. The time had come, however, for the church to take a public stand.

While eventual Union victory had become virtually certain by the early months of 1865, how long the horrific war might drag on was far from clear. Thus, Adventist leaders took further measures to make known to military and state authorities their position and the recognition granted the church by federal authorities.

Uriah Smith and James White filed “duly sworn” affidavits in Calhoun County, Michigan, declaring participation in warfare and bloodshed to be violations of the core beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists. Smith’s statement refers to the “Church Covenant” adopted by the Michigan Conference in 1861 as indication that Seventh-day Adventists had always “taken as their articles of faith and practice, ‘The Commandments of God and the Faith of Jesus Christ.’ ” He elaborated that Adventists explain “the commandments of God to mean the ten commandments of the moral law, and the faith of Jesus Christ to be the teachings of Christ in the New Testament.” James White stated that he had been a minister of the “denomination” since 1847 and “that during all of that time, the teachings of that church have been that war is sinful and wrong, and not in accordance with the teachings of the Holy Scripture.” Copies of these affidavits were appended to a pamphlet published in 1865 with the title Compilation or Extracts, From the Publications of Seventh-day Adventists Setting Forth Their Views of the Sinfulness of War, Referred to in the Annexed Affidavits.

The church also made formal its commitment to pacifism in a resolution voted by the General Conference Session of 1865:

While we thus cheerfully render to Caesar the things which the Scriptures show to be his, we are compelled to decline all participation in acts of war and bloodshed as being inconsistent with the duties enjoined upon us by our divine Master toward our enemies and toward all mankind.12

Further resolutions at the 1867 and 1868 sessions reaffirmed this position.13

Our Adventist pioneers were not perfect. Nor do all their views hold the status of absolute dogma for members today. Yet if we take seriously the calling to be a faithful remnant, we would do well to pray for a measure of their wisdom and courage as we grapple with what “the commandments of God and the faith of Jesus” mean with regard to war, violence, peacemaking, and love of enemies in our time.

1 Reports on Klimkewicz may be found at the websites of the Adventist News Network (www.adventist.org) and the Adventist Peace Fellowship (www.adventistpeace.org).

2 Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), pp. 188-212.

3 See Ronald D. Graybill, “The Abolitionist-Millerite Connection”; Ronald L. Numbers and Jonathan M. Butler, eds., The Disappointed: Millerism and Millenarianism in the Nineteenth Century (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), pp. 139-150; and Peter Brock, Freedom From Violence: Sectarian Nonresistance From the Middle Ages to the Great War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), pp. 230-258.

4 Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1948), vol. 1, p. 264.

5 Read James White’s views in a series of three articles collectively entitled “Ellen G. White—Racist or Champion of Equality?” in the Review and Herald, Apr. 9, 16, and 23, 1970.

6 D. A. Robinson, A. L. White, and W. C. White, “The Spirit of Prophecy and Military Service,” manuscript (Silver Spring, Md.: Ellen G. White Estate, 1936), pp. 6, 7.

7 Brock provides a thorough analysis of the Civil War-era debate in the Review and Herald over military services in Freedom From Violence, pp. 230ff.

8 “To Correspondents,” Review and Herald, Sept. 9, 1862, p. 118; “The War Question,” Review and Herald, Oct. 14, 1862, p. 159; “Letter to Bro. Carver,” Review and Herald, Oct. 21, 1862, p. 167.

9 E. G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 1, p. 361.

10 “Eastern Tour,” Review and Herald, Sept. 6, 1864, p. 116.

11 J. N. Andrews, “Seventh-day Adventists Recognized as Noncombatants,” Review and Herald, Sept. 13, 1864, pp. 124, 125.

12 “Report of the Third Annual Session of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists,” Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, May 17, 1865, pp. 196, 197.

13 “Business Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Session of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists,” Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, May 28, 1867, p. 284.

This article originally appeared in the June 14, 2007, Adventist Review. At that time Douglas Morgan was professor of history and political studies at Columbia Union College (now Washington Adventist University) in Takoma Park, Maryland. He now serves as an assistant editor of the Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists and teaches church history courses for the School of Distance Education, Andrews University.