Two physicians from Loma Linda University Health, a Seventh-day Adventist healthcare institution in Loma Linda, California, United States, have recently established the first physician-run epilepsy treatment programs in the southeastern African nation of Malawi.

Warren Boling and Travis Losey traveled last year to Malawi, where there are scant resources for treating the estimated 900,000 Malawians believed to be affected by the disease. Losey says there were only a handful of nurse-run clinics in the entire nation where patients could receive treatment for epilepsy.

Boling, a professor and chair of neurosurgery at Loma Linda University School of Medicine, and Losey, medical director for adult neurology at the Comprehensive Epilepsy Center at Loma Linda University, established the treatment programs at Malamulo Adventist Hospital in rural Makwasa, and Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Malawi’s second-largest city, Blantyre. They took a video Electroencephalography (EEG) system with them to record electrical patterns in the brain, enabling physicians to diagnose seizures, convulsions and related disorders.

In the West, epilepsy — a neurological malady that causes sufferers to lose consciousness or experience uncontrollable convulsions due to abnormal electrical activity in the brain — is a common brain disorder, affecting roughly one percent of the population. But in some developing countries, it is far more common. Losey said an estimated 1 out of every 20 of the 18 million residents of Malawi suffers from the disorder.

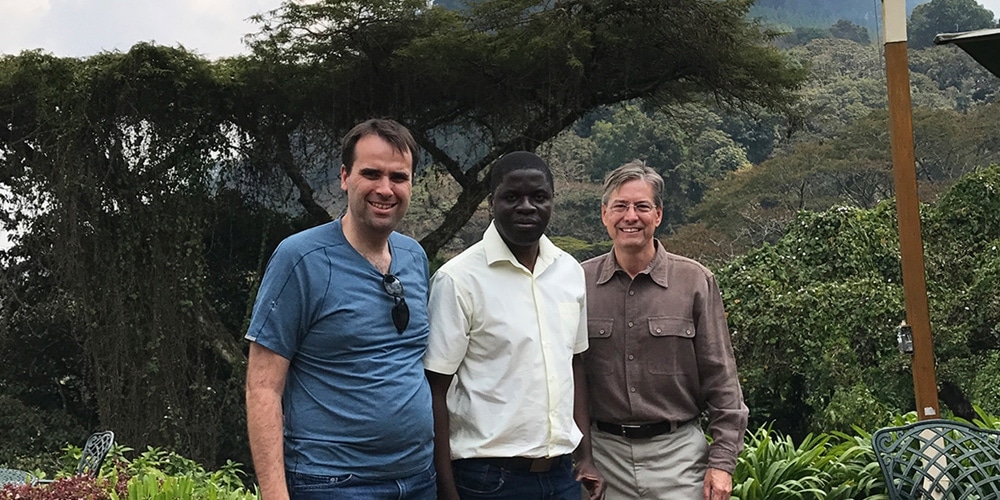

In setting up the new centers, Boling and Losey worked with neurosurgeon Patrick Kamalo at Queen Elizabeth, and internist Timothy Gobble, a 2012 graduate of LLU School of Medicine, at Malamulo. Although Boling and Losey returned to Loma Linda in early September, they maintain close contact with their Malawian counterparts through virtual technology that allows them to consult on patient cases and continue the peer-mentoring process from afar.

Malamulo was founded in 1902 as a mission outreach of the Seventh-day Adventist Church and is located in a sparsely-populated area famous for growing tea, coffee, and macadamia nuts. Queen Elizabeth, on the other hand, is located in a city of more than 1 million people and affiliated with the University of Malawi College of Medicine. The two hospitals are located approximately 30 miles from each other, which enables the sharing of resources and expertise.

Epilepsy has long been misunderstood. In the past, people with epilepsy were sometimes thought to be demon possessed or insane. In recent years, however, as diagnosis and treatment have improved and the public has become better educated, the stigma of epilepsy is reducing in the West. However, in most parts of the developing world, including Malawi, epilepsy-related stigma is a widespread problem impacting people with epilepsy.

While a number of factors have been associated with the disease, it can still be difficult to pinpoint the exact cause in a given patient. Sometimes congenital conditions or genetic factors are involved, at other times stroke, Alzheimer’s disease or head trauma plays a role. Regardless of the cause, several treatment innovations are currently available to help people with epilepsy live full and meaningful lives.

Boling and Losey are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the advancement of epilepsy care in Africa and plan to return next summer to continue to educate the medical community and public about epilepsy and to further develop the diagnosis and treatment centers they initiated in 2017.

“In the meantime, we’re staying in touch through virtual reality,” Losey said. Boling notes that virtual technology makes it possible to share a high level of expertise with their African colleagues. “If you had to travel there every time you wanted to see a patient, that wouldn’t be possible,” he said.