, editor of Semnele Timpului, the Romanian version of the Signs of the Times

Indian writer Salman Rushdie famously warned that freedom of expression would die if people didn’t have the right to offend one another.

“What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist,” he said.

Rushdie himself faced death for exercising his “freedom to offend” in his 1988 book, The Satanic Verses, Ben Wizner, a director of the American Civil Liberties Union, noted in a 2012 commentary published by PBS television.

Ayatollah Khomeini, the supreme religious leader of Iran, issued a fatwa ordering Rushdie’s death on charges of insulting Islam, sending the author into hiding for nine years. But Rushdie’s “freedom to offend” had consequences: one of his translators was stabbed to death, and dozens of people died in protests against the book.

On Jan. 7, 2015, a dozen people were killed in Paris as a result of the same freedom to offend. Among the slain employees of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo were four cartoonists who drew irreverent depictions of Islam and its prophet, Muhammad.

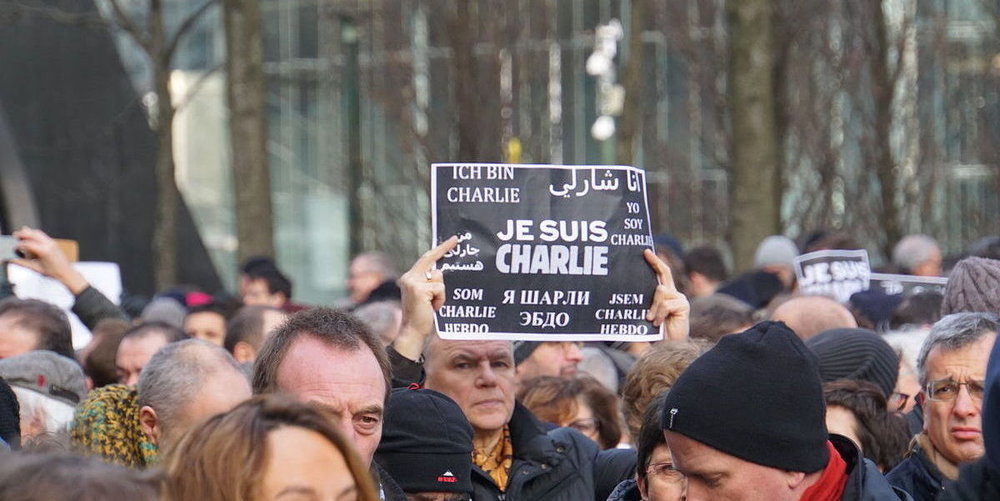

The massacre by two Islamist gunmen resulted in an outpouring of emotion, with scores of people rallying on the streets and social media to declare, “Je suis Charlie,” or “I am Charlie.”

I am a Christian. I am Charlie, too.

Christians have no problem joining people around the world in condemning the Paris killings. We have a biblical basis for our stance, the sixth commandment, which outlaws murder.

But Christians also know that the Bible extends the principle of love to loving even your enemies (Matt. 5:44), and that makes the cartoons published in Charlie Hebdo appear to be unnecessary and inappropriate provocations.

See also

4 Lessons for Adventists From the Islamist Attack in Paris

Adventist Church Offers Condolences After Islamist Attack

The magazine’s cartoonists knew they were stirring up anger in some quarters. “It perhaps sounds a bit pompous, but I prefer to die standing than living on my knees,” one of them, Stéphane Charbonnier, said in 2012. To be fair, Charbonnier also said he disliked all religions equally. An avowed atheist, he said, “Islam is just as banal as Catholicism.”

So Christians may rightly feel perplexed about what position they should take personally and as a society toward those who boldly and blatantly exercise their freedom to offend.

Some people have seen advantages in restricting free speech and the freedom of expression. Eric Posner, a recognized authority on international human rights law at Chicago University, has suggested that a government’s desire to protect the freedom of expression should not prevent it from halting the distribution of offensive materials if the restrictions could prevent deadly protests. Posner was specifically referring to a parody film called Innocence of Muslims whose online distribution in the West in 2012 sparked violent protests in the Middle East and North Africa.

The simple solution may appear to be to outlaw extreme forms of free speech. But there are two real dangers with this line of thinking.

The greatest danger was succinctly expressed by Wizner in the PBS commentary: “The only thing predictable about giving the government the power to censor speech is that it will use that power unpredictably."

Those words resonate with people like me who live in communist or former communist countries. The recent past is enough to remind us that the idea of giving the authorities the right to censor speech creates threats much larger than those that arise from the expression of offensive opinions.

The second danger lies in the fact that the beliefs of one person may offend another, especially when it comes to religious matters. Given the opportunity, some people would criminalize anti-gay activities, while others would criminalize any activity that was pro-gay. Likewise, some people would criminalize religion, others atheism; some abortion, others the so-called pro-lifers. The results would be tragic, as demonstrated by the recurrence of persecution throughout world history.

Therefore, we need to protect the freedom of expression of everyone, even as we discourage speech that incites hatred. We need to defend the freedom of both those who embrace a religion and those who mock it.

Religious liberty and freedom of conscience can never be invoked to justify retaliation against those who mock a religious belief. As Asma Jahangir, former United Nations special rapporteur on freedom of religion and of conscience, once said, “Freedom of religion primarily confers a right to act in accordance with one's religion but does not bestow a right for believers to have their religion itself protected from all adverse comment.”

I would like to believe that support for the freedom of expression of all people was what motivated people to flood the social media with their message of solidarity, “I am Charlie.” When we defend the freedom of those who offend us, we are defending our own freedom.