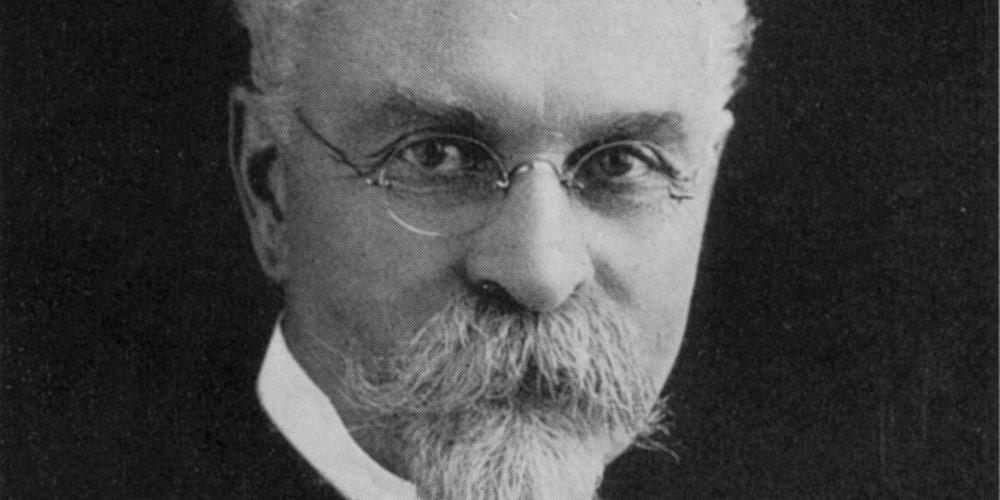

Arthur Grosvenor Daniells was elected General Conference (GC) president in 1901, a significant General Conference session, because the church structure was completely reorganized. The restructuring was actually much of Daniells’ idea, so he seemed a natural choice. Now, almost 10 years later, in 1910, Daniells found himself president of a much larger church.

When Daniells was elected, the membership was 78,000. His presidency saw a growth rate of 25 percent. But growth wasn’t simply membership. More local and union conferences were established, leading toward an increased bureaucracy. Church institutions showed growth as well, with 28 publishing houses, 74 sanitariums, and 680 schools. All might have seemed well, but, in fact, 1910 proved to be one of Daniells’ more troubling years.

To give some context, one must first go back a few years. In 1907, W. W. Prescott, GC vice president and Review editor, introduced some “new” theology concerning the “daily” in Daniel 8. This opened some debate and study sessions, and eventually led to sides being taken. Daniells, while cautious, thought Prescott’s view held merit.

By 1909, it was time for another GC session. Grumbling about Daniells’ leadership permeated the camp. Ellen White, who was in attendance, heard more than a few people share their opinions on both doctrine and the president. While the issue was not on the agenda, a theological cloud overshadowed the meetings.

For the previous five years Ellen White had been sending repeated communications to Daniells about city evangelism. While he dealt with administrative issues, including this ongoing theological debate, she, in turn, pressed for a focus on evangelism to large cities.

At the 1909 GC session, she surprised the leaders by declaring that W. W. Prescott should be relieved of his duties as Review editor and sent to New York City as an evangelist. Thinking they did not understand her correctly, they questioned her several times over a period of months. She was resolute. By 1910, Prescott was in New York, but unhappy with his assignment.

A. G. Daniells, on the other hand, was doing all he could to take her requests seriously. Leaders appropriated $11,000 especially for city evangelism. They had dispatched Prescott to New York. Daniells planned a five-day meeting dedicated to discussing the topic. Whatever progress he thought he’d made didn’t make a difference; White continued to urge the need for larger plans. Her son, W. C. White wrote: “Mother’s burden for the cities continues. It is pressed upon her mind night after night that we are not doing what we ought.”1

More time passed, and Ellen White continued to express her dissatisfaction. “What can we do? What can we do to persuade our brethren to go into the cities and give a warning message now, right now!”2

In California for meetings in May, Daniells traveled to Ellen White’s home at Elmshaven, hoping to surprise her with the news of his plans for city evangelism. But when he arrived, he was stopped at the door. The prophet declined to see him, sending a message instead: When he, the General Conference president, was ready to carry out the work that needed to be done, she’d talk to him. Rebuffed, Daniells boarded a train for home.

Feeling the sting of rejection, Daniells was confused. Hadn’t he done what he could? The money, the committees, sending the Review editor to the field? What more could be done? What did she mean? The answer came in a package of letters in late June. Ellen White had lost her confidence in him. Clearly, more plain speech was required, and it came in two decisive statements.

“Had the president of the General Conference been thoroughly aroused, he might have seen the situation. But he has not understood the message that God has given. I can no longer hold my peace.”3

The second, however, was a bigger blow, as recounted by Daniells himself, in 1928:

“Finally I received a message in which she said, ‘When the president of the General Conference is converted, he will know what to do with the messages God has sent him.’ . . . That message, telling me that I needed to be converted, cut me severely at the time, but I did not reject it. I began to pray for the conversion I needed to give me the understanding I seemed to lack.”4

Clarence Crisler, one of Ellen White’s secretaries, tried to persuade her of the things Daniells was doing right. But she was undeterred. He reported:

“Sister White touched on the blessing that would come to the general work if Elder Daniells and some of his associates who are bearing large responsibilities could personally enter the cities and act as leaders. . . . As the General Conference brethren labored for souls in the great cities, their sympathies would be enlarged, and their minds would be so fully occupied with the work of thwarting the efforts of Satan to win the allegiance of the world, that they would lose sight of petty differences of opinion on doctrinal points.”5

To Daniells’ credit, he had great respect for Ellen White and her prophetic calling. While he was hurt, he did not cast off the testimony, but rather began some serious soul-searching. He also did not keep it quiet. On July 1, 1910, he shared all of Ellen White’s letters with the General Conference Committee. That day they took an action to relieve A. G. Daniells of his administrative duties for such a time as he could go to New York and personally conduct an evangelistic meeting—still president, but totally focused on sharing the gospel with those in the city.

In that same committee they appointed 17 men whom they assigned to four geographic regions to begin aggressively conducting city evangelism in major U.S. cities. Daniells was energized by his experience in New York City, so much so that he wrote to Ellen and W. C. White expressing the sentiment that he’d be happy to lay aside his presidency and focus on evangelism. Her reply dissuaded him of this path.

“The position you have taken is in the order of the Lord, and now I would encourage you with the words, Go forward as you have begun, using your position of influence as president of the General Conference for the advancement of the work we are called to do.” She added, “Angels of God will be with you. Redeem the lost time of the past nine years by going ahead now with the work in our cities, and the Lord will bless and sustain you.”6

A. G. Daniells was changed by this experience, painful as it might have been. By spending some time in the field winning souls for Christ, he gained a new perspective that transformed the way he spent his time and his emphasis as an administrator.

Much could be taken from Daniells’ experience, but the one truth that seems best is that mission changes lives. Certainly sharing the gospel with others brings them to Jesus and saves them for eternity. But doing mission, whether overseas or in your backyard, changes individuals. We see what God values. What we might have thought important fades as we work for Him.

Merle Poirier is operations manager for Adventist Review.