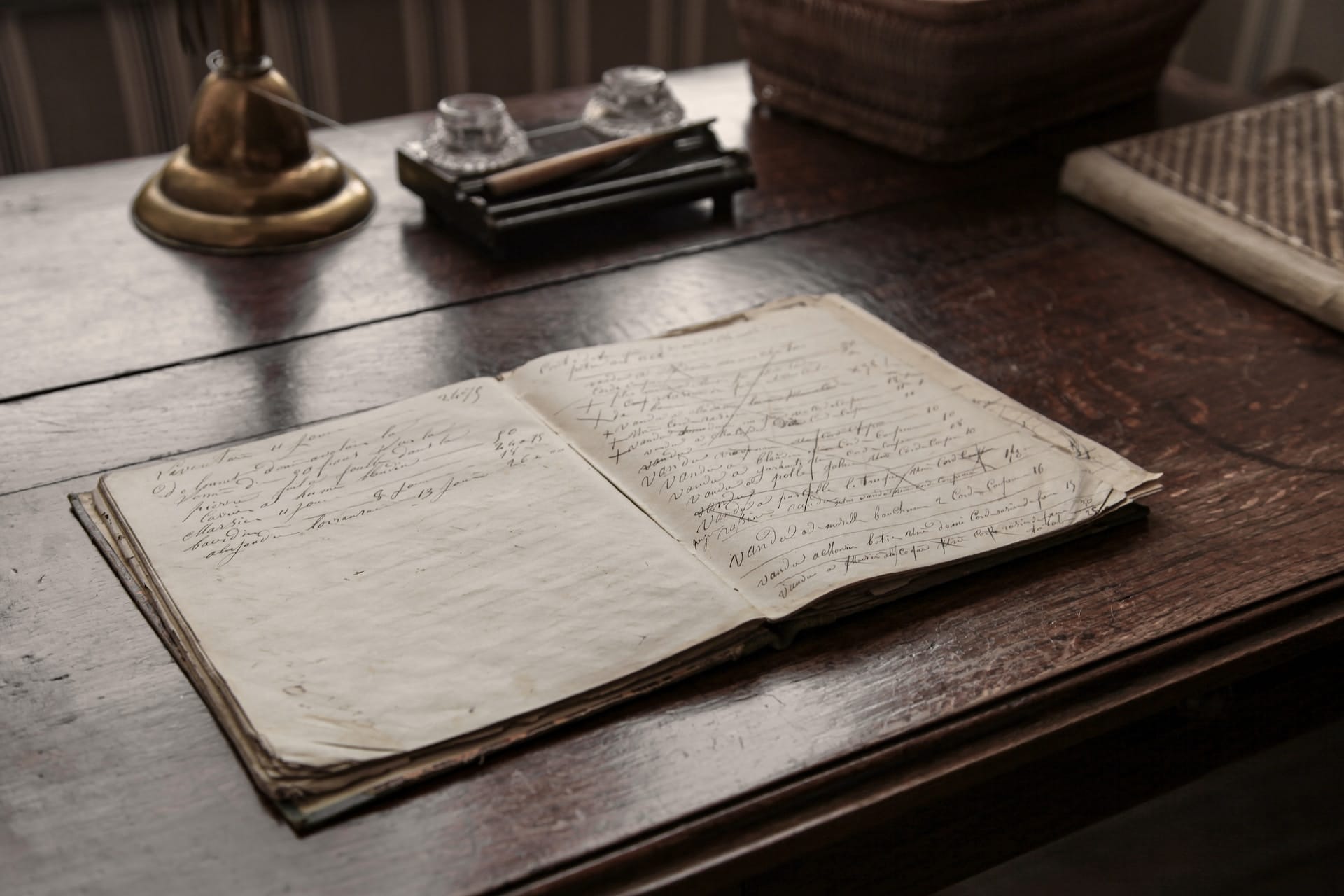

Ruth Matsumura sat by her mother’s bed in the small, plain room. She was only 11 years old, but she was mature enough to sense the importance of what was happening. Her eyes were on her mother, who sat propped up on pillows, writing in a small black book. “I am writing down how often you should wash the sheets,” said Tokino Matsumura. She stopped and looked into Ruth’s eyes. “Women are strong. You must be the strength of the family. They must not see you cry.”

Time was running out for Ruth’s mother. There was no cure for breast cancer in 1937. She would no longer be able to care for her husband, her daughter, and her three sons. So she earnestly scribbled down housekeeping instructions and recipes. “Never fight,” she told Ruth. “People might cheat you, but you must never cheat them.” She tried to think of any advice that would help her daughter navigate the future without her. “Learn to play an instrument,” she said. “It will bring you pleasure for the rest of your life.” She paused, then spoke as if she were saying a prayer: “God will take care of you,” she said.

Life as They Knew It, Over

The immigrant family lived just west of Sacramento, where James Matsumura farmed 17 acres of apricot trees. When his wife’s struggle ended, he buried her among the blossoming orchards.

The family moved to the Bay Area, and Ruth began attending Mountain View Academy. She earned her way by living with a family in nearby Palo Alto and helping with their cleaning and washing.

That job ended abruptly on December 7, 1941. The family told Ruth that she needed to leave. “We don’t want a Jap living in this home,” they told her.

She was still welcome at Mountain View Academy. Ruth Wiest, the English teacher and a graduate of Union College in Lincoln, Nebraska, was especially kind, and several teachers wanted to protect this slight, sweet-natured girl. They were especially concerned to hear of plans to imprison all the Japanese on the Pacific Coast. Miss Wiest reached out to her former dormitory dean, Pearl Rees. Principal Westermeyer wrote to his brother-in-law, the business manager at Union College, “If there is any way you can accept this girl as a student, you will save her from going into government detention.” It was letters at first, but as time ran out, they picked up the phone to make expensive long-distance calls.

On Friday, March 27, 1942, the Army announced that no one of Japanese ancestry would be able to enter or leave the West Coast “exclusion zone” after that Sunday. On the morning of March 29, Principal Westermeyer greeted Ruth at the entrance to Mountain View Academy. “You need to go back home and pack a suitcase,” he said. “We have only today to get you out of California.”

Heading East to the Midwest

Miss Wiest hugged her goodbye at the train station. “You’re going to Union College,” she said. “They will take care of you.” As the train rolled through the Sacramento Valley that night, Ruth tried to imagine what Union College would be like, but her imagination collapsed under the weight of loneliness. She knew she was blessed to have a way of escape, but the loneliness continued.

After two days on the train, Ruth arrived in Nebraska. She was welcomed by Pearl Rees and the college business manager, H. C. Hartman, and his wife. It was cold, and Ruth had only a spring jacket and light dresses to wear. Her bare legs broke out in rashes. After securing a coat, Mrs. Rees made sure she got a hat and gloves immediately. The dean was strong in the opinion that “a lady doesn’t go to church without a hat and gloves.”

Ruth remembers the first time she stepped into the cafeteria. “The shocked students put their forks down and stared at me,” she recalls. Many had never seen an Asian before. It embarrassed her. “I told Mrs. Rees I didn’t want to go back to the dining room,” she remembered. But the dean smoothed things over. Soon Ruth was back in the cafeteria experiencing Midwestern cuisine. One day she tried a bite of cabbage. I must let them know this is spoiled before someone gets sick, she thought to herself. She did speak to the staff, only to be told that sauerkraut was supposed to taste that way.

She was instructed never to leave the campus alone. In 1942 the people of Lincoln felt no love for the Japanese. A gold star family ran a fruit stand down the street. Who knows what would happen if she crossed paths with this family, who had lost a son in the conflict. On a shopping trip with Mrs. Rees, a stranger pointedly asked if Ruth was Filipino or Japanese. It frightened her, and all she could do was nod her head.

Ruth heard that her father and little brothers had been taken to an internment camp in Wyoming. She would see them only once for the duration of the war. But despite the loneliness, she showed a spirit of gratitude. She liked her job in the furniture factory, where she made chairs and playpens. “Mr. DeVice, the man in charge, was very kind to me,” she recalls. “I could work whenever I wanted to.” Mr. Jorgenson, the chemistry teacher, reached out to her and invited her to lunch at his home. A good friend, Juanita Lamb, invited her to her family home in Iowa for Christmas. Ruth didn’t know until later how much effort it took for the family to get a permit to bring a Japanese to their town. Afterward she refused invitations to travel for the holidays.

Carried

Anonymous friends from California regularly sent money to Ruth in the mail. She had no other means of support. “Remember that picture of footprints in the sand? I think I was just carried,” Ruth said. She was being taken care of, just as her mother had promised. God was showing up through teachers from Mountain View Academy, Union College faculty, and

new friends.

She chose to study nursing, remembering some of her mother’s parting words to her. “I hope you become a nurse, because you’ve been such a good nurse to me.” She finished her degree in 1946 and moved back to the West Coast. The first money she earned was spent on a memorial headstone for her mother.

Ruth married Ichiro Nakashima, a graphic artist, and settled in the Bay Area. They raised two sons and two daughters. Ichiro worked for Pacific Press Publishing Association, and Ruth spent most of her career at Stanford University Medical Center. “My life changed because I was able to get an education,” she states. “I had to go to a strange country, but the country was very kind to me. I think God led me to Union College.” Today she lives in Sacramento, California, near her children. In the spring Ruth takes her family out to visit her mother’s grave, where they picnic under the almond blossoms. She keeps the small black book with her mother’s instructions on the nightstand beside her bed. “My mother said that God would take care of me, and He did.” She smiles, reflecting on her 98 years of history. “And someday soon I’ll see how He did it.”