The people you meet in the next three articles share recollections of the pleasure, the pain, and the privilege of witness they enjoyed as young Adventist Christians in a variety of sports contexts. Memories range from little league, through high school to Olympic Games participation. Each testimony is unique, spiritually grounded and instructive of faithfulness: engage, enjoy, be inspired, and visit the Adventist Review website at www.adventistreview.org, to learn much more of the story each of our interviewees has to tell.—Editors

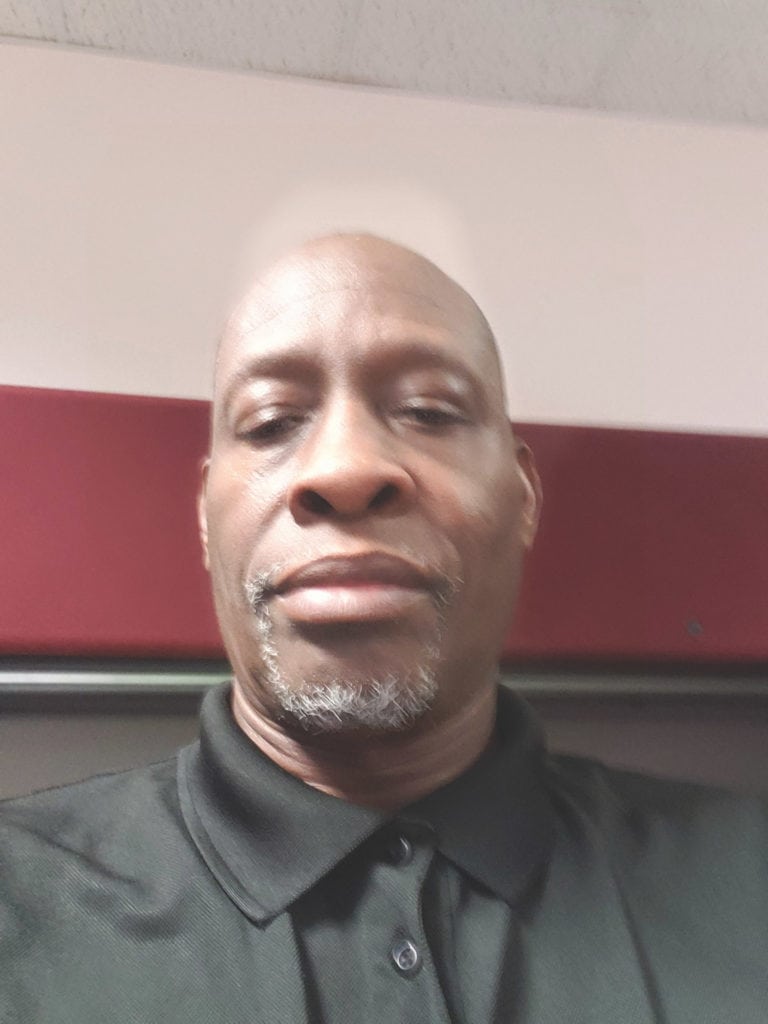

Isaiah Jones is a shipping agent at the General Conference and an elder of Emmanuel-Brinklow Adventist Church. Learning the fundamentals of athletic skills in his small, segregated Southern town in North Carolina, he says, gave him life skills. He played Little League football and baseball until he matriculated to basketball.

ADVENTIST REVIEW: Why basketball?

IJ: I just felt I was better, more talented, in that area.

I see.

IJ: I went to basketball and played team sports. I’ve never, I guess, engaged in a sport in which I was solo; it was all team sports. And as I said, I felt that it taught me how to be a team player. It was the good of the team versus me. On some teams I was one of the better players, but you just learned that as in Christianity, it’s not so much about you, but about the gospel message reaching others. . . . That’s victory. So from early on, we were taught about being a team player and just supporting your teammates, being your best, doing whatever you had to do for the team to win.

Any prizes?

IJ: Yeah, all the way from Little League sports. We won championships and got a trophy: individual trophies, team trophies. In high school it was the same, all the way up to my first year at community college: playing basketball, we won the championship.

Today, if you are a superstar athlete and you say something, it seems to weigh as much as if you are the governor or the premier, the prime minister or the president. Did involvement with sports give you credibility with your family or with your community, or with the Adventist church you were a member of ?

IJ: More so in the community. My Adventist church did have a basketball team, which I played with. And so you were just respected. You were not revered—just respected, but you know. When I started in the church, part of the ministry of the church team was going to other Adventist churches to play with them. But to be a part of that, you would have to give the AYS [Adventist Youth Society] program.

And we were encouraged to have non-Adventist people come and be a part of the team so they could get to know the ministry. So from that perspective, that involved us. And even when I came into the Maryland area and they had a basketball league here, that was the same thing we did as we travelled—we presented programs; and other non-Adventist people got to see what a Christian athletic program was like.

What else can make you say, Sports did this for me; sport taught me this?

IJ: It taught me that I had to persevere. When you’re training and going through the preparation of being a team member, you learn that you have to work through the pain. Some coaches would tell you to win at any cost; but most taught you values: you didn’t cheat; you didn’t try to injure the other player, though you wanted to win. It helped my church life. Growing up Adventist, you have church friends and you have non-Adventist friends, but it helped transition. A lot of the values I got playing sports were the same as those at church.

Were there other things that you saw besides the good in sports?

IJ: Yeah. There’s always that temptation, you know. If you have talent and skill, you’re invited to parties. There’s revelry, drinking, drugs. There were some athletes who were very highly skilled, and they would do whatever they needed to do. When you have values instilled in you early on and through the church, it conflicts with your morals. Not saying that I never made any mistakes or anything, but faith was in you and part of your DNA, so you just could not. And believe it or not, most players respected you for the stand you took and your beliefs. They would always say, on Friday, “Oh, Isaiah, I know your Sabbath’s coming, so I know you’re not gonna come with us to this event or that event.”

Were there times the team pressure was on you to do something for the sake of the team that wasn’t...?

IJ: Yes. Yes. On the championship teams, when you’re pursuing a championship or you get to the playoffs, they want you to play. When I was younger, I did have a decent skill level, so they would say, “Well, we can’t win if you’re not here”; or “We need you.” So that pressure was big. And it was very hard not to give in to that pressure, because you feel like you’re gonna let the team down, or if they didn’t win, maybe if I was there, I, I could have helped them win. But God always worked it out, and they won the games on Friday nights. But I did feel that pressure.

Here’s my biggest question: What kind of counsel do you have for kids who are at the age you used to be when you were playing sports and winning championships?

IJ: You have to be grounded, and true to yourself. One person that I have come to admire is former NFL player Colin Kaepernick for taking the stand that he did to call attention to racial injustice in the United States. I would encourage young players to stand for what they believe in, ‘cause there’s gonna be pressure, whether it’s for money, fame, especially if you’re very talented. You just have to be grounded and stand for what you believe. Many young people don’t get the advice that you and I got about right and wrong and how the choices you make affect your life. So that’s what I would pass on to them: that the choices you make will affect you.

You want to say something about how sports teaches you about God . . .

IJ: Well, in the Black community, church was such an integral part of the community, that all of that came together. You were being told that the talent and gifts you had were given to you by God, and that you used them to benefit others—the team, your community. The world doesn’t revolve around you. I was a team player, and so when we would not listen to some of the things the coaches would say, they would sit you down on the bench [laughs]. And you had to think about your behavior. And it just made you realize that there were consequences to your actions. And if you didn’t listen, there were also consequences. So . . .

That sounds like a God who’s got commandments and we’d better obey them.

IJ: Right. Sports taught me perseverance. If your skill set wasn’t what you thought it should be, then you persevere, you practice—that is, you pray daily and communicate with God, your spiritual life will increase. If you read your Bible and study and pray, you get better understanding, and you’ll be better able to witness to others about God and who He is, versus a quick prayer here and there, hit or miss. . . . I always told my children, “You can’t introduce somebody to somebody you don’t know.” If you don’t know God for yourself, you can’t introduce other people to Him.

Before Lisa Beardsley-Hardy was Education Department director at the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, she was on both track and swim teams at public high schools in upstate New York, competing in the low hurdles, the 100-yard dash, and the quarter-mile relay. In the pool she raced in freestyle and butterfly events. Sabbathkeeping forestalled much of her competitive participation. Memories of those days on the boys track team include the coach giving his athletes little Snickers bars for energy, and her dad giving her icicles or ice cream to run with him. Less-pleasant memories include a teammate setting a hurdle at irregular distance, causing her to crash and hurt her knee—she’s still dealing with the aftereffects. We take up the conversation as she talks about winning and losing.

ADVENTIST REVIEW: In athletics I imagine sometimes you or the team won and sometimes you didn’t. What did losing teach you?

LBH: That it’s just a game. Learning to lose fairly and without carrying that around with you. There’ll be another meet, there’ll be another game, and we need to continue training. It’s not a matter of luck. It’s a matter of training.

What good life lessons has sports taught you?

LBH: It was an athletics director at Andrews University that summed it up well years later and put a label on what was my experience. He said that there’s a role for athletics in an Adventist school because athletics, and participation in athletics, teaches things that you could never learn in an English class or a history class.

Yes.

LBH: It teaches you to manage your emotions. When you’re all pumped up and the adrenaline is going and you are just out for winning and you’re part of a team—in that context, one can lose one’s temper. One can become a sore loser. One can say things that they would never say if they were in a classroom. So it activates a part of you that is simply not activated in a traditional learning center, and gives you multiple opportunities to learn to manage your emotions, to be a fair player, to be a good sport, to be Christlike even in the heat of the moment.

Did you see other sides [of sports]?

LBH: Yes. Injuries. Coaches that are too focused on the win and not mindful of the health and well-being of their young people. And something like football is quite barbaric. The pounding. Because I was out there on the track, running around, I’d see the football players in the middle doing their training. It’s brutal. Just the training itself. And the coach shouting and pressing and . . . And then a game can be even worse.

Things like boxing I don’t think should be considered a sport at all. Even high school level football . . . , I feel that the risks to health, potential head trauma, the emotions that it arouses, are ones that are not helpful and have long-term consequences. So, personally, I think that the non-contact sports are in an entirely different class. But even there, there can be some injuries.

Superstars like tennis player Naomi Osaka and gymnast Simone Biles have brought to public focus the issue of mental health. Do you have something to say about that?

LBH: Well, thank you for raising that. I pointed out the effects on physical health, but absolutely, there is also the pressure for mental health. And when individuals’ very sense of self and identity gets so tied up, and they make compromises as believers, Seventh-day Adventists, and make compromises and play on the Sabbath. . . . I know of some instances in which they sacrificed their most cherished values, allegiance to God. Then, when the athletic career did not move forward, they were emotionally damaged and spiritually damaged. I thank the Lord now, in retrospect (although at the time I felt embarrassed), that I did not go to meets on Sabbath, though on Friday night I felt like I was letting down my team. But I see now that those were opportunities for me to keep my life in balance, and to guard my mental and spiritual health. Those at the extreme ends, they get pushed. They get pushed like fine thoroughbred horses. They get pushed by their parents, by their peers, by their coaches, and emotionally it’s not a healthy level of pressure. And for most of them there’s not a Sabbath that helps them put all of this in the proper perspective that God is first and allegiance to God is first.

I’m wondering what you do about that as a high school kid. What can a high school kid do in the face of all this pressure from the school in general and, specifically, the athletics department and, directly, their coach? And then, of course, parents who’ve got wondrous illusions?

LBH: Those are real pressures. And a young person does not have the emotional maturity or the years or perspective on life that an adult would have. Much of this responsibility needs to go to the parents. And yes, parents, I have heard the arguments: exercise is good. It’s healthy. It builds team spirit. But I have seen lives severely impacted when parents have allowed the thrill of the sport to cloud and to rearrange their own values.

From a distance now, what two or three bits of counselling would you have for yourself that you learned from your involvement and that you want to carry with you as a professional woman, as informing your career?

LBH: For me the most valuable part was the training. And even if I had not competed in a single [race], that developed attitudes toward wellness and habits of relating, and understanding the relationship between effort and outcomes; the need to be a positive team player; to be a good team member on and off, out of the game. And those are things I couldn’t have learned in an English classroom.

What counsel do you have for 16- and 17-year-olds who are where you used to be?

LB: I would say remember the Sabbath day.

Anything beyond the Sabbath you might want to tell them?

LB: That’s a good question. I would say to honor God, and that’s the Sabbath, a tangible way to seek balance, development. And parents have to be partners in it. And teachers have to be partners in that. This is why a Seventh-day Adventist education is so important. Teachers are partners. In my public school it was very disaggregated. The coach did this. The teachers did this. The principal is over here. Your classmates are here. There wasn’t anybody bringing that all together in an integrated fashion for wholistic education in me. Adventist education does bring that together and teachers are partners in a way that doesn’t happen in public schools.

The second thing I would say is for parents to send their kids to an Adventist school and for students to ask their parents to send them to an Adventist school so that they can grow wholistically—physically, emotionally, academically, absolutely. And for those who are in public schools, I would say you have to be the captain of your own team and honor God in all things.

Are there any overarching principles you would say that a young, athletically gifted Christian youth can never afford to forget?

LBH: It comes again to honoring God, to seeing athletics or the performance in the context of the giftedness that God gives you, the opportunity that you have for witness, and that witness might be in keeping the Sabbath. It can be in playing fair. Whatever that context is, that’s an opportunity to use the gifts, and point to God, and realize God’s plan for you.

Finally, what are some of the greatest challenges you are aware of to keeping the principles that you’ve mentioned?

LBH: I think one of those is learning to be in the moment in a Christlike way; not allow that rush of adrenaline [laughs]. You’re pumped when you’re going all out and you don’t want to let your team down. It’s a very powerful experience, physiologically and emotionally. So learning to tame the tongue, to manage the emotions, to be a good sport, to recognize that whether you win or lose is not your worth as a human being. Your worth as a human being is assigned by God and cannot be earned and cannot be taken away by performance. To recognize the opportunities in that moment.

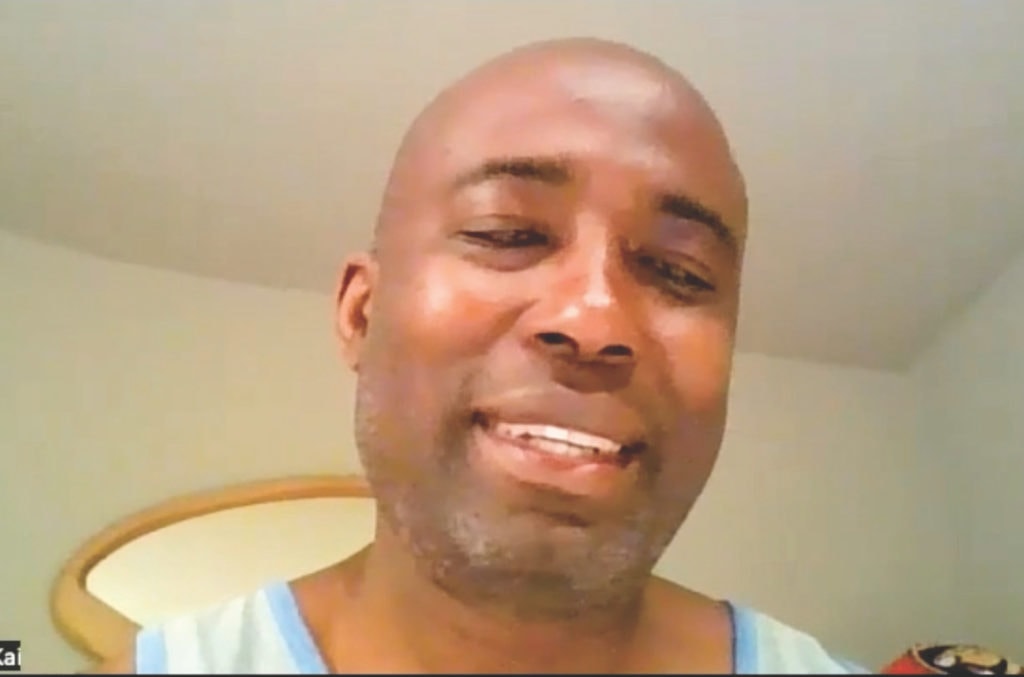

Sheridon Baptiste is a Canadian three-time Olympian, and former national long jump champion. An inductee into the nation’s track and field hall of fame, Baptiste was a top performer through high school, university, and beyond. He seemed to sparkle in all things sportslike: team sports—basketball, football, hockey; individual events—from track sprints to table tennis. He traces it all back to when, as a little boy in Guyana, his mom told him, “Go outside and play.” After graduation from Queen’s University he was drafted for Canada’s pro-football league, the CFL, by the Ottawa Rough Riders. Though he graciously yet determinedly resisted discussing his championships and trophies, he was willing to answer queries about how he was treated.

ADVENTIST REVIEW: How did people at home, friends and relatives, people at school, people in the community, relate to you, because of . . . ?

SB: I’ll be honest with you, In ever thought about things like that. But obviously at this point in my life, or even much earlier, it gave me the opportunity to do a lot of things: to go into schools and speak to kids; to be a communicator and an advocate for sport. It opened up so many doors.

If somebody asked you, “What does sports— track, swimming, bobsledding—have to do with real life?” What would you say?

SB: It teaches you discipline. You have to be on time; you have to take care of things you’re supposed to take care of. It teaches you hard work, it teaches you honesty, and it teaches you dedication, trust, setting goals, loyalty, all the kinds of things that are really important, I think, in life.

What do you think of medals and ribbons as a way of defining life and success?

SB: It’s not a way to define success; it’s not a way to define life. I’ve been on both sides, you know. I was inducted into the Queen’s [University] track and field hall of fame. It’s like the equivalent of Ivy League.

You’re telling me it isn’t really the best way to define life and success.

SB: It isn’t, because I’ve done stuff; I’ve won stuff; but I’ve lost a lot too. And I think there’s just as much value in losing as there is in winning.

Really? I don’t know anybody who wants to be called a loser.

SB: Well, being called a loser, I think that’s something that’s defined by you. If you want to consider yourself a loser, that is your prerogative. But I believe that in everything in which you lose, for instance, a race, you can go back and look at that race and figure out why you lost and try to improve on that. Otherwise, you’ve failed. So you have to learn how you can get better from the things that you have lost in. I think a lot of people probably use the word “loser” because it makes them feel better.

Now, I’m thinking, You know what? He can say that because he has won a lot. So what about the people who have never won a ribbon? never won a medal? never won a prize?

SB: I honestly believe that every person has something in them that they are good at, that they can succeed at. I don’t care what it is. If you’re a great server, you’re unbelievable at what you do. The losing, I think, is something defined by people who want to put you down personally. If you allow them to put you down, then you have a problem.

You’ve been talking about the bright side of sports, even if it involves some people getting medals and others not. But sometimes it seems that sports have another side, a dark side. Tell me what you make of that. How do you respond to that side of sports?

SB: That’s a fair question. And again, it’s choices that we make, right? I chose to compete as a Christian athlete. I chose to compete because I wanted to serve my Lord; to glorify my Lord in the abilities that He has given me. Some people compete because they want fame, they want glory, they want money. They want all the things that the world has to offer them. And they’re willing . . . .

What two or three principles do you see undergirding sports across the board—track and field, team sports, swimming?

SB: For me it’s fair play. And that was one of the biggest for me—only because of the way I grew up. I really didn’t have that much. And I just remember a few instances of sneaking into the gym or the weight room because I just didn’t have the money.

What would you say to youth—high school, college, or university youth—who are now at the age you were at in the late 1980s? What would you like to tell them about sports and athletics?

SB: Well, I honestly believe it’s important in life to find something that you love doing. And if that’s sports, so be it; if that’s sewing, so be it. Just find what you love and serve your Lord. I would also say, “Don’t allow others and your circumstances to determine who you are.” You determine that for yourself. Set goals, and don’t be ashamed to change those goals once in a while. Set lofty goals, but don’t be afraid to modify those goals.

Amen. On the other side, are there some principles that good athletes could never afford to forget?

SB: A lot of people probably think that most athletes think about the great things that they did, such as the medals they’ve won, the races they’ve won, the prize money. But I’ll let you in on a little secret: most athletes who really care about themselves and really have a sense of being a good athlete—they remember the failures.

Huh?

SB: As strange as that is, I can vividly remember my failures; I can remember that touchdown pass that I dropped, or that basket I missed at the end. And I think, I can’t believe I missed that shot. You might have scored 30 points that game, but what you remember is I can’t believe I missed that shot. Those are the things that most athletes actually remember.

So what happens if you forget the shots you missed?

SB: Well, I think that if you forget those, then you fail. You honestly do. You need to think, If I’m in that situation again, this is what I’ll have to do to do better. And it’s probably like that for everyone in every job. Is it not? You remember the scenarios that you didn’t succeed in, but you do your best to make sure that if it happens again, you’ll know what you’re going to do to make it better.

You’re not a current Olympian. What, from those days, do you still hold before you always? SB: For me personally, it’s not the medals, it’s not the winning. It’s the relationships that you developed, the people that you have influenced in a good way. I remember that when I was an athlete, the guys were always on me: “Sheridon, you never go out with us. Why don’t you go out with us? You don’t drink. Why don’t you drink? You don’t eat pork. Why don’t you eat pork?” And I just talked to them about those things and talked about my religion and influenced them in whatever way that I could. Those are the little things that I remember. We won a lot of medals. We were very successful, though I didn’t win any Olympic medals.

You don’t get to the Olympics without winning gold medals.

SB: We won a lot of stuff on the world cup circuit in bobsledding. We went to different countries and competed in a lot of different venues, and that was our circuit. And track and field was the same way. But those things were just not as important as the relationships that I formed over the years. For instance, when I was on the circuit, one of the people who competed was Prince Albert of Monaco. Things like that are what you remember—you know, the camaraderie you had. I don’t miss the training. I don’t miss the hard days. But you miss just hanging out with the fellows and talking.

Isn’t that beautiful, because there’s a lot of that in heaven. We may not be competing to see who finishes the track faster, but we have a lot of time to hang out.

SB: The greatest champion is Jesus. The greatest Teammate lifts all those around Him. The greatest Captain builds an everlasting team.