Queen Esther answered, ‘If I have found favor with you, Your Majesty, and if it pleases you, grant me my life—this is my petition. And spare my people—this is my request. For I and my people have been sold to be destroyed, killed and annihilated. If we had merely been sold as male and female slaves, I would have kept quiet, because no such distress would justify disturbing the king’” (Esther 7:3, 4, NIV).

“For my people everywhere singing their slave songs repeatedly: their dirges and their ditties and their blues and jubilees, praying their prayers nightly to an unknown god, bending their knees humbly to an unseen power.” This is the opening stanza in Margaret Walker’s famous poem “For My People,” originally published in 1942.1 Walker’s imagery and metaphor personify her people. They are those who sing songs of sorrow and jubilee, who “bend their knees to an unseen power.” Beyond simply being overcome by sorrow, Walker believes African Americans are a people filled with much joy and laughter. At the end of her poem she cries out to “let a people of loving freedom come to growth. Let a beauty full of healing and a strength of final clenching be the pulsing in our spirits and our blood. . . . Let a race of men now rise and take control.” Hers is a call for a revolution that turns what is seen as the sociopolitical tide of destruction, death, and extermination to a tide of life, liberty, and freedom.

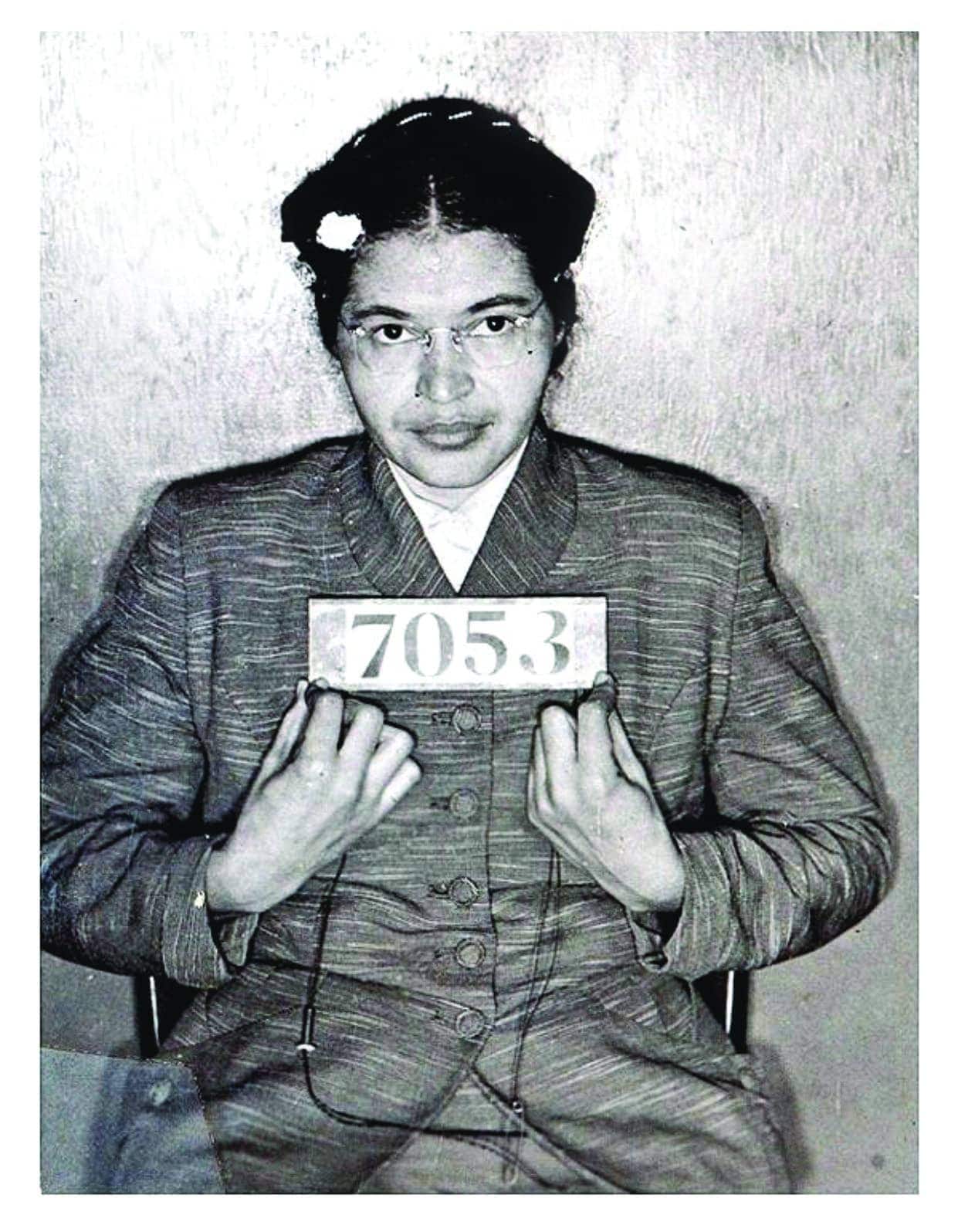

Of critical importance is the fact that Walker is not the first Black woman to call for such a revolution. For years African American women have contributed backbone, hands and feet, as well as brains, to many significant social movements of their race and broader society. A proper telling of history would recall there is no emancipation without Harriet; no civil rights without Rosa; and movements for justice in our day are no less dependent on the commitment of women leaders. Black women have consistently been both at the heart of our calls for revolution, and—if we are truly honest—at the engines firing the fuel that maintains them.

This reality of Black women’s central involvement in America’s past and present social justice movements has caused me to ponder the question: Why do Black churches’ promotion of activism and the project of social justice as a prophetic anointing seem reserved exclusively for the male gender? Why do Black churches not celebrate the activism of Martin Luther King with properly balanced mention of Prathia Hall? Why don’t Black churches celebrate the activism of Nelson Mandela with properly balanced credit to Miriam Makeba? Why don’t Black churches celebrate the activism of Jesse Jackson alongside properly balanced mention of Shirley Chisholm?

It seems to me that a major reason that Black churches are more comfortable with men as the spokespersons for justice; that Black churches share stories chronicling the lives of men so much more than women as the leaders and sustainers of the work for social justice; that Black churches may neglect fair reference to women as they champion the efforts of male leaders engaging in the work of social justice, is that our social justice theology is based predominantly on the activism of men in the Bible. The next social justice sermon you hear, as well as the last one you heard, is probably on either Moses, the great emancipator; Jeremiah, the weeping prophet; Micah, the justice expositor; or Paul and Silas, the great liberators. This patriarchal lens through which we often read social justice in the Bible is itself unjust, erasing, as it tends to do, the female activists of Scripture. Such a reading effectively delivers the message that activism is most properly enacted by men.

Such interpretive practice communicates to the girls and young women of our churches that it is appropriate to support a man’s social justice vision without motivating them to have their own. They have learned that it is fine to be the sounding board to a man’s prophetic voice. They have not learned that it is appropriate to develop your own. Overlooking the leadership roles of women of the Bible as change agents in the communities of antiquity teaches our girls more often than not that it is normal—yea, honorable—to work for freedom, sacrifice for equality, even die for justice, and be forgotten.

I readily acknowledge the importance of recognizing the sacrifices and contributions of African American men to church and community leadership. I also insist that there is a need for more of another emphasis, that of celebrating the history of progress within our churches and communities led out by women, female leaders who often enough remain invisible, whose contributions may go unchronicled, sacrifices unacknowledged, and strategic ability unappreciated. I call the names of women leaders such as Georgia Gilmore, who cooked meals during the civil rights movement to feed the leaders and fundraise for the boycotts; women leaders such as Prathia Hall, who inspired the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr., just from their prayers. Truth be told, it was at a service at the Mount Olive Baptist Church after their church was burned by the Ku Klux Klan that Prathia Hall stood before an audience that included Martin Luther King, Jr., and prayed a powerful prayer, repeating the words “I have a dream.” Moved by the phrasing, King asked permission of Hall to include the expression in his sermons, leading up to his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington just one year later.

The limited knowledge of such women stories illustrates an intentional or unintentional erasure of Black women from the nation’s and race’s activist narratives of social engagement. The lack perpetuates a long history of sexism between men and women, both African American and other. As Margaret Walker said in 1979: “Even in pre-civil war days, black [sic] women stood in the vanguard for equal rights [sic] for freedom from slavery, for recognition of women as citizens and co-partners with men in all of life’s endeavors. . . . However, because of the nature of American history, and particularly because of the institutions of slavery and segregation, the names and lives of black women leaders are all but unknown in American society.”2

Scholar Bernice McNair Barnett has surmised the reason for this practice: “Although they have traditionally performed crucial roles and have been considered the ‘backbone’ in the church, Black women historically have not been allowed the opportunity to become ministers, deacons, or trustee—the ‘heads’ and top decision makers in the male-dominated hierarchy of the Black Baptist Church.”3 This failure to give Black women legitimate church authority equates to the inability of many to acknowledge their spiritual gifts and capabilities, divinely bestowed, within the church, let alone without, in the wider community.

Theologian Jacquelyn Grant posits that there has been a misunderstanding of the compliment “backbone.” While we have taken it to mean Black women are a sturdy skeletal structure keeping every single aspect of protest programming in operation, it seems as though “most of the ministers who use the term have reference to location rather than function. What they really mean is that women are in the ‘background’ and should be kept there.”4 Nevertheless, had it not been for the courage of Black women, the protests of Black women, the activism and rebellion of Black women, who knows if, as a people, we’d still have been sold to destruction, death, and extermination far beyond 1863. The unstoppable energy, the voice, the political strategy, the inspiration, and the sustenance characteristic of Black churches owes much to a host of Black women who woke up every morning and said, “for my people.”

Queen Esther may have been the first woman to declare “for my people.” Holding one of the highest positions in the land, Esther is made aware that her people are facing the threat of genocide for no other reason than their nationality and culture. Her cousin Mordecai sends her a message:

“Do not think that because you are in the king’s house you alone of all the Jews will escape. For if you remain silent at this time, relief and deliverance for the Jews will arise from another place, but you and your father’s family will perish. And who knows but that you have come to your royal position for such a time as this?” (Esther 4:13, 14, NIV).

Realizing that her people are victims of targeted systematic and institutional extermination, Queen Esther takes on a critical leadership role to ensure the preservation of her people; a role whose price could very well be her life.

Esther’s example shows that the exclusion of women leaders is unbiblical. It is exemplary of women have been at the forefront of leadership and protecting their communities since Bible times and in the Bible’s own stories. Declaring “for my people,” Esther shows us what it means to assume a leadership position and not allow the structures, customs, or policies of the establishment to prevent you from enacting justice.

In fact, Esther’s example reveals that it is better to risk one’s life attempting to do right than to seek to save one’s life by avoiding conflict. Put another way, individuals who truly believe in the responsibility of “for my people” believe that it is better to die demanding that God’s love be seen in the earth than to live silently while injustice reigns while justifying our silence with the claim of awaiting Christ’s second coming.

I believe God is looking for a generation of women who are willing to take up the mantle of their foremothers and declare “for my people.” We need such courage for the sake of making mass incarceration a bondage of the past; for illiteracy to become a forgotten story; for diabetes to be cured; for food deserts to be filled with stores selling fresh groceries; for mental health to be normalized, treated, and eliminated; for mountains of debt to be paid off and familial wealth generated; for girls to grow up knowing that they can be preachers, strategists, organizers, fundraisers, cooks, singers, teachers, yea, the very face of social justice. God is looking for a generation of women willing to lead for Him, within our churches and in the broad communities where they live, giving their all to transform their world while declaring, with Queen Esther, “for my people. . . ; [and] if I perish, I perish.”

1 Margaret Walker, For My People, ed. Stephen Vincent Benét, Yale Series of Younger Poets (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1942), pp. 13, 14.

2 See Bernice McNair Barnett, “Invisible Southern Black Women Leaders in the Civil Rights Movement: The Triple Constraints of Gender, Race, and Class,” Gender and Society 7, no. 2 (June 1993): 162-182, web accessed Dec. 11, 2021.

3 Ibid.

4 Jacquelyn Grant, “Black Theology and the Black Woman,” The Black Studies Reader, ed. Jacqueline Bobo, Cynthia Hudley, Claudine Michel (Oxfordshire, Eng.: Routledge, 2004), pp. 421-433, web accessed Dec. 11, 2021.

Claudia Allen is a teacher, preacher, and writer on culture, religion, justice, and truth, who lives in the state of Maryland.