Adventists are nice? Says who? And how about God: Is He nice? What would He have to do for you to think of Him as nice? And back to the Adventists: How would they answer the question about their being nice?

We haven’t yet even agreed on what’s “nice.” So let’s make it simple by consulting a good dictionary. Except that dictionary answers this time around seem a mind-boggling complication, exposing dramatically contrasting meanings of this four-letter word through the centuries: stupid and refined, simpleminded and delicately discriminating, wanton and modest, dissolute and scrupulous—all meanings of “nice.”

1 Who wants to be “nice” if what that means is “stupid” or “wanton” or “dissolute”?

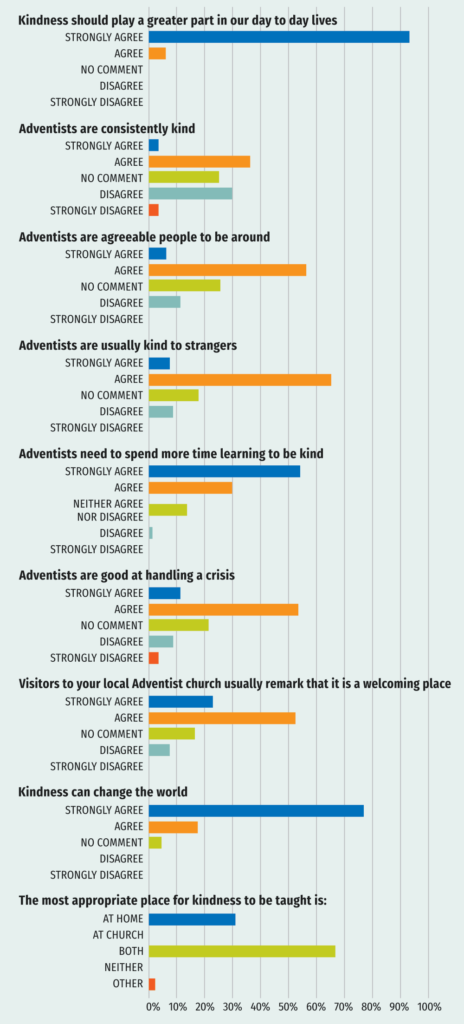

Despite the broad scope of its meaning through the years, a recent survey on Adventist social media (November 13-18, 2018) suggests that there is strong consensus currently on a positive understanding of the term.

Merriam-Webster offers “kind” as a synonym for “nice,” and 100 percent of survey respondents agreed that “kindness should play a greater part in our day-to-day lives.” More precisely, 6 percent agreed and 94 percent strongly agreed with the statement.

So how do Adventists stack up against something so thoroughly desirable as being kind, i.e., nice? Are Adventists as committed to being kind as they are to believing in kindness? Given that two of the many senses of “nice” are “diffident” and “reticent,” we may say that Adventists in the survey were nice about their response to how nice they are. Whether it was their caution, conscientiousness, or conviction, only 41 percent of respondents agreed that we are consistently nice or kind. Consistent with that doubt about consistent kindness, 85 percent believe—including 54 percent who strongly do—that we need to spend more time learning to be kind.

How would we learn to be nice and kind? In his book Where Are We Going? Jan Paulsen, a retired General Conference president, has mustered the courage to tell an awkward story of his own. His story is awkward because it illustrates how much of the road toward spiritual maturity in Jesus Christ still lay before him even as a church leader. At the time of the episode he relates, Paulsen was president of the Adventist school in Bekwai, Ghana, and pastor of the campus church.2 Informed that one of his teachers had taken a second wife, Paulsen writes, “I went to him and laid down the law.” The teacher would have to put away his second wife. Paulsen explains the mind-set that impelled his administrative action: “To the pure mind of a young missionary polygamy was absolutely intolerable.” But his concluding remarks on the episode offer us strong indication on the contrast between being what we may call “a principled Christian” and being a nice Adventist. Paulsen lays it out as a “lesson for a well-intentioned missionary.” “Christian values can be communicated ever so harshly if compassion for the human element is missing. Being kind is every bit as important as being right.” He adds, “I have found that sometimes my church is much better at being right.”

Reflecting on Paulsen’s narrative brings to mind my own experience as a ministerial intern learning from one of Adventism’s giants in leadership—though you would not know it if you looked at him the way the prophet Samuel first looked at Jesse’s sons. Samuel’s deficient spiritual vision invited God’s rebuke, “Do not consider his appearance or his height” (1 Sam. 16:7). My teacher-trainer-pastor was no Eliab: Hilton Garnett stood small where Eliab stood tall. But Garnett was God’s giant, because, among other things, he knew, as said of Jesus, “what was in each person” (John 2:25). Garnett was compassionate toward humanity because he understood human nature.

We would meet at 8:00 a.m. in the vestry of the largest church in his district to plan the day’s activities. Member visitation featured prominently in those plans. With just the two of us in the room, Garnett would fume and rage about the unforgiveable behavior of a Sister Ex or Brother Why. More than once during my time with him, his denunciations primed me to expect a mighty confrontation when we got to someone’s door. Even as we approached that door I would be ready to see how he would “fix” the sinning member. Then when the door opened, Garnett would dissolve into pure meekness and mush, solicitous greetings and caring conversations.

Jesus’ message disrupted the spiritual, social, and political status quo without Him ever becoming political.

With board meetings and nominating committees it was different. Garnett didn’t fume, but committee members did. He would listen as the rants raged on. Righteous indignation would flare from the lips and eyes of Christian committee members intolerant of sin, so intolerant that guilty Brother Why would never, emphatically never, be allowed to serve the church in whatever capacity again. Then Garnett would meekly deliver the punchline, simple and fundamental, compelling and almost comprehensive,

3 that he had internalized through the years, and that he lived out in our pastoral visits: “Brethren, you have to remember that we are dealing with people.”

I would venture with Paulsen’s support that as Adventists, we are more willing than many—if not most—Christian groups and denominations to dedicate good, worthwhile time to dealing with issues of doctrine, to splitting hairs on prophecy, and earnestly contending for the fate of some given policy. Finding counsel from Jesus on our preoccupations with the lighter elements of the law—the non-people matters—instead of what mostly counts for God, “justice, mercy and faithfulness” (Matt. 23:23), can be profoundly distressing. But because Jesus “was never rude, never needlessly spoke a severe word, never gave unnecessary pain to a sensitive soul,” and because “He did not censure human weakness,”

4 our distress may not come principally from the words He speaks. What may most embarrass us is our memory of when and to whom He first spoke them.

For example, He may repeat to us words previously spoken to religionists we fervently despise: “The Sabbath came into existence for human beings’ sake, not the other way around” (see Mark 2:23-28). “Which is lawful on the Sabbath: to do good or to do evil?” (Luke 6:9).

Overall, the language does not drip with insult. Except perhaps for an occasional occurrence of a word like “hypocrite.” For example: “You hypocrites! Doesn’t each of you on the Sabbath untie your ox or donkey . . . ?” (Luke 13:15). Even so, we may be able to handle them except that they remind us so pointedly of Jesus’ first audience. Confusing enough for good Christians, Adventists included, Jesus first spoke these words to His stalkers, the Pharisees, who were always “on to Him” (Matt. 9:3, 4, 11, 34; 12:2, etc.) and whose thoughts went straight to murder once they had heard His lines. Once He had rebuked them and undone sin’s physical victimization for the sufferer before Him, “the Pharisees went out and plotted how they might kill Jesus” (Matt. 12:14).

Here’s the problem: I doubt that any of us dreams of growing up to be Pharisees. We are much more likely to fantasize about how nice people think we are. And regardless of its apparently confounding meanings through time, we know for a surety the difference between being called “nice” and being called “Pharisee.”

Admittedly, avoiding or perhaps escaping the “Pharisee” label in our pursuit of the “nice” one can be a challenge. If today’s Pharisees are anything like their originals from Jesus’ time, they are still people of epic holiness, and laypeople at that: people who aren’t Pharisees because they get a salary for it. Conforming to the first-century model, a Pharisee’s God-commitment is the stuff of public prayer celebration. The rank and file esteem their spirituality a thousand times—or some other grand multiple—more than that of the official church administration. Jesus’ Pharisees were as pure and conscientious as the priesthood was slack and corrupt: their regimen of fasting was impressive; their faithfulness in tithe paying was a religious showpiece; their largesse on behalf of “the work” was conspicuous; their dedication to the study of the Word commanded the awe of the God-fearing citizenry, and exposed the apostate farce of Jerusalem’s theological and administrative officialdom. The faith and exegesis of those officials aligned altogether more with Greco-Roman books and thinking than with any of Moses’ compositions or argumentation. The Jew in the street knew this; and the Pharisees themselves knew it too. It was the stuff of their public conversations with God: “praying with themselves” is what Jesus called it (Luke 18:11, 12). Would Jesus want to say to us today what He long ago had to say to Pharisees?

Luke 18 does a good job of laying out the “Pharisee-problem.” In Luke’s prayer story, “the Pharisee stood and prayed thus with himself, ‘God, I thank You. . . .’” (verse 11, NKJV).5 His enumeration of actions calculated to establish his “creds” may be only illustrative. He may have omitted other equally consequential proofs of his goodness—helping elderly women across the street four times per month; volunteering at the Y; annual mission trips to dangerous if also exotic destinations; serving on some regular schedule, whether weekly or monthly, at the local soup kitchen; and who knows what more!

Compassion is a significant element of being nice, and Jesus had it in abundance.

But in the grand scheme of things, in the ultimate determination of life or death, exhaustive documentation would help no more than the Pharisee’s short-list of examples does. For either of them, short or longer, exposes the mentality that drives his goodness: his virtue is measurable by visibility, mathematically calculable, scientifically verifiable. It is his life by appearances that will be his death and eternal disappearance. It is goodness by numbers, by pluses and minuses: fasting twice a week; avoiding the behaviors of robbers, evildoers, adulterers, and tax collectors (again, verse 11).

Goodness by numbers, by pluses and minuses, aligns the spiritually misguided with the physically dead, to the extent that neither of these is involved in robbery, evildoing, or tax collecting. Goodness by numbers works on the face of things instead of down in the hold, extolling particular furniture arrangements on the deck of the doomed and sinking

Titanic. Its ledgers of debts and accounts receivable foster decent relationships, pleasant neighborhoods, even exceptional service and philanthropy, and funerals that are celebrations of arrival at oblivion.

Optimism and humaneness are not the same as salvation. They save no one from sin and eternal loss. They have no answer to Jesus’ momentous question: “What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul?

Or what can anyone give in exchange for their soul?” (Mark 8:36, 37). Even being nice has its limits. For esteemed as an end in itself, it may provide a cover for the deadly menace that is the suave social elegance of an unconverted heart: “The love of influence and the desire for the esteem of others may produce a well-ordered life. Self-respect may lead us to avoid the appearance of evil. A selfish heart may perform generous actions.”6

Paulsen would no doubt insist that while we should never abandon our commitment to doing what is right, we do ourselves, our neighbors, and the cause of God no good by a lack of compassion in our living. Compassion is a significant element of being nice, and Jesus had it in abundance: “When he saw the crowds, he had compassion on them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd” (Matt. 9:36).

His concern was not limited to surface matters; His inner thought was not

I really hope the people like My new sandals. He did not live for appearances and He did not judge by appearances. Hear Him again, engaged with the crowd, including His ubiquitous companions, the Pharisees: “because Moses gave you circumcision (. . . actually . . . the patriarchs), you circumcise a boy on the Sabbath. Now if a boy can be circumcised on the Sabbath so that the law of Moses may not be broken, why are you angry with me for healing a man’s whole body on the Sabbath? Stop judging by mere appearances, but instead judge correctly” (John 7:22-24).

He knew where He was from, why He was there, where He was going, and how to judge. His person, His manner, His message disrupted the spiritual, social, and political status quo without Him ever becoming political (“Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s,” [Matt. 22:21]), because the ways of God will inevitably confound the ways and style and order of fallen humanity. And when the corrupt religious administration united with the laity of dedicated Pharisees to put a stop to Him, the guards they sent to arrest Him returned empty-handed. Their commissioners asked, “Why didn’t you bring him in?” “‘No one ever spoke the way this man does,’ the guards replied” (John 7:45, 46). Which Ellen White explains: no one ever spoke like Him because no one ever lived like Him: “His words bore with them a convincing power, because they came from a heart pure and holy, full of love and sympathy, benevolence and truth.”7

It may be that being nice is the wrong goal after all, the wrong focus for Adventists, the superficial one. Maybe the goal should be deeper and higher. How about being like Jesus? For as one respondent to our recent survey opined (see p. 35): “The closer we get to Jesus, the kinder we will be.” And reading with

Merriam-Webster, we may say, “The closer we get to Jesus, the nicer we will be.”

Lael Caesar has no objection to “nice-ness,” but mostly he longs to be like Jesus. He is an associate editor of Adventist Review.