For our special focus on faith and economics three career economists agreed to share their stories with us. Margarett Enniss-Trotman works as an economist and strategic planner with a large nongovernmental organization; Gomez Agou works at the International Monetary Fund headquarters; Colin Bruce recently retired as senior adviser to the president of the World Bank.—Editors

Thank you, friends, for being willing to share yourselves with us. Perhaps each of you can begin by telling us a bit about yourselves.

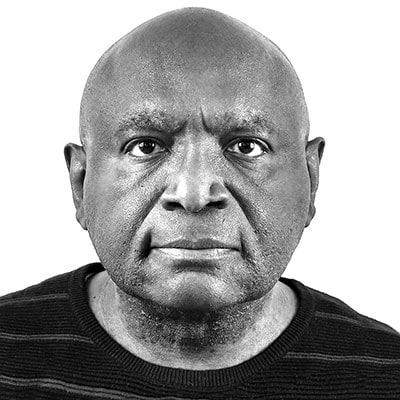

Gomez Agou (GA): I’m a 35-year-old economist with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). I was born in Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s biggest producer of cocoa. My wife and I have two kids, a 7-year-old girl and a 4-year-old boy.

Colin Bruce (CB): I’m Guyana-born, but I’m a citizen of the world, having lived in a half dozen countries. My parents lost six of their nine children shortly after they were born, and I lost another sibling to a car accident in Canada in 1980. My wife, Laverne Bentt, is an anaesthesiology professor, and our two kids are both in postgraduate studies.

Margarett Trotman (MT): I’m also Guyanese, and my name is a legacy of my country’s colonial history when parents loved to name their kids after members of the British royal family. So I’m Princess Margaret with a distinctive spelling, Margarett. Unlike Colin, eight siblings and I have grown to maturity. My husband, Roderick, is a deeply spiritual man, and we have one young adult daughter.

That’s a good segue, Margarett—your deeply spiritual spouse. Talk about your faith background.

MT: My family heritage is steeped in Adventism. My maternal and paternal grandparents, myriad uncles, aunts, and cousins were adherents as was my mom. My dad, though he grew up in the church and was a strong supporter, waited until age 75 to be baptized.

CB: My mother did the beat—church attendance, Pathfinder Club membership, caring ministry to needy neighbors, everything with me in tow. I made my commitment at 12 years old.

I guess we all can thank our parents.

GA: Yes, my dad’s father was a pioneer of Adventism in Côte d’Ivoire, a man of faith to whom I owe a lot of my own. But I started my personal walk with the Lord when I was 14.

Talk about your choice of career.

GA: Poverty made me choose economics. I grew up puzzling about it, loved math in college, and learned that it was a good base for becoming an economist. I got admitted to a French elite school training in statistics and economics. Following graduate studies in economics and statistics, the IMF hired me as national economist for Côte d’Ivoire. As I dove into the sea of economic issues faced by the government entangled with other public policy challenges, I decided that I needed to know more. Columbia, Princeton, and Harvard accepted me, and I chose Harvard. Upon graduation from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government in 2014, I rejoined the IMF at its headquarters in Washington, D.C.

MT: Can I say “by accident”? In high school I was progressing well as a science student, excelling in math, physics, chemistry, and biology. But I needed three electives to complete my class load: I picked Spanish and geography. What else? I picked economics and got hooked. Economics was about real life. As class sessions progressed, my interest was piqued as I started to make connections between what I was studying and what I was observing in my own life. I started to understand how scarce resources were being distributed in my large family; why my parents’ household financial decisions were mostly based on our needs and not our wants; and why transactions with my siblings sometimes bore reasonable benefits and sometimes generated unbearably high costs.

CB: In high school, economics provided the most compelling concepts and tools to understand people, households, firms, communities, nation states, and regional economic blocks; how they interacted with one another to create value, and how they tried to fix problems that occurred among them. Economics usually involves working with numbers, and I love numbers.

The only thing you can take with you out of this world is your faith.

My passion for the subject grew when I realized that it provided insights into a wide range of practical issues, such as why families have so many or so few children; why three-lane highways should be built in some areas and not others; why floods in Pakistan can affect the economy of Egypt; why a dollar provided to a worker today might be more valuable to him than $10 paid at month’s end; and, at a personal level, why I was obsessed with time and far less with money.

One more explanation: I was under considerable pressure from my church community to become a pastor or a medical doctor. Choosing economics was an act of youthful rebellion. But I committed to doing well and doing good, God helping me.

Say more about how a high school kid attains the global perspective you’re talking about.

CB: Well, you can credit both world and church. In the 1960s we had no Internet or television services, so reading was my window to the world. My dad insisted that my sisters and I read newspapers every day to familiarize ourselves with domestic and international affairs. Around that time the nonaligned movement was taking shape as many former colonies obtained their independence. Leaders such as Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah and Sri Lankan prime minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike visited our shores, and their worldview appealed to me.

Within Adventism, stories of missionaries introduced me to the idea of serving in far-flung places. Providentially, I ended up going to universities that nurtured such interests, and this became my gateway to employment in the premier global development organization.

How have faith and profession affected each other?

CB: My faith has gifted me a very clear purpose for living, a passion for fairness, a respect for all peoples, and a disciplined and independent mind. My mother helped me understand that purpose with the words of a song: “Help me to live for others that I might live for Thee.” Working in global economics and in humanitarian affairs allows me to do this at scale. My faith has also given me unbending resoluteness in pursuing that purpose, and a quiet peace amid the fiercest personal and professional storms that life routinely brings.

GA: My job as an economist and public policy maker is to improve the lives of humans through a better management of country economies, particularly developing countries. Helping others, improving people lives, is what Christians are supposed to do on earth to witness the Word of God. So I do my job daily with one thing in mind: doing the right thing for the glory of God first. As an IMF economist, I advise sometimes on tough economic decisions. No matter how difficult and urgent the decision may be, I always ask myself how it is going to impact human beings—children of God; then I try to minimize the negative effects, if any.

MT: Practically speaking, my profession influences how and where I serve the church. For instance, I see connections between our stewardship doctrine and economics as it relates to resource use and allocation, and environmental preservation and conservation. I serve as a stewardship leader. I also serve on the finance and budget committee and enjoy working with youth to provide counsel on debt management, budgeting, and financial planning.

Conceptually, the idea that betterment of and for humanity is common to both my faith and my profession as an economist, is somewhat intriguing. I can see how the message of the cross, how a Savior executing a solution for the world’s sin problem to redeem us back to God, is in some way reflected in the discipline of economics that’s heavily focused on developing solutions and fixes for economic problems, albeit temporal.

That being said, we must be careful that we don’t make economics a type of religion that replaces faith in God. Some time ago I read in The

Guardian an intriguing article by John Rapley titled “How Economics Became a Religion.” In it he likened economics to a religion that offers comprehensive moral instruction “that promises salvation in this world and seeks to give guidance on how to reach a promised land of material abundance and endless contentment until reality forces a retreat from its claims, and the model no longer fits.”1

One more question and a wrap-up: What should earlier economic downturns—recessions (2008-2009), depressions (1929-1930s)—have taught us as Christians? More particularly, as Seventh-day Adventists?

GA: I’d mention two things. First, everything is vanity. You can lose everything, including your life, in this world in a very unexpected way. The only thing you can take with you out of this world is your faith. So preserve your faith. Second, Jesus is still coming back soon. The Bible has warned us. So let’s get ready to meet Him.

MT: Can I tell a story? Saving for a rainy day is an important principle for many responsible adults, and it was for me too. As such, I had savings and investment bank accounts, and got into the habit of rolling over the investments at the maturity date to compound the returns.

So when I visited my bank Globe Trust and Investment Company in January 2003 and rolled over my investments as per habit, I didn’t have the slightest inkling that the bank would fail within a week and that I would lose the majority of my savings. To make matters worse, I fell ill and needed surgery three days later, a surgery that almost took my life and that required a three-month recovery period. To compound matters, we were on track to immigrate to Canada, and would need the lost funds.

Acting purely on economic principles, I completely disregarded the possibility that an omniscient God would choose to test me when I least expected it to strengthen character and to build trust in Him. I confess that as the stress and worry mounted during this dilemma (my sickness [and recovery] and the loss of a significant sum of money), I learned to rely on God, not on markets or money. What was taken away, He restored.

CB: I’d like to go to a Bible story. Joseph’s youthful dream forewarned him of a global famine. Later, as Egypt’s prime minister, he built a strategic food reserve and fed the masses. He also remained spiritually alert. When his starving brothers came calling for help, he not only provided food but seized the opportunity to restore their broken family ties.

God has done his part to forewarn us that economic downturns, natural disasters, and other crises will occur with greater frequency and intensity. We must do our parts to prepare and prevent the worst consequences. Competent leaders create sound contingency plans, organizations adjust and improve, and individuals learn to cope better.

What parting word do you have for those who will hear and see what we’re sharing here?

MT: Our only hope is to trust in God. It is clear from earlier economic recessions that human systems will fail and fall, only to be propped up and fall again. In contrast, the kingdom of God will never fail; it will stand forever. A good picture to keep in mind is the rock striking and crushing the mixed-mineral feet of the image in Daniel 2, which thereafter filled the whole earth.

GA: Despite all these challenging times, we should never forget that Jesus loved us first and still does.

CB: Amid the ongoing turmoil, let’s remember that “we have nothing to fear for the future, except as we shall forget the way the Lord has led us, and His teaching in our past history.”2

1 www.theguardian.com/news/2017/jul/11/how-economics-

became-a-religion

2 Ellen G. White,

Life Sketches of Ellen G. White (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1915), p. 196.