I have recently been contemplating the parable of the good Samaritan, a true incident with which Jesus answered a lawyer’s question “Who is my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29). Through this well-known story Jesus taught three lessons to His listening audience, lessons readily understood by honest truth seekers, and lessons sorely needed right now, in the presence of popular pride and prejudice, even among many who identify as Christ’s followers.

The truths Jesus reemphasized are all taught in the Old Testament, the only Bible He had, the one He taught, leaving the people “amazed at his teaching, because he taught as one who had authority, and not as their teachers of the law” (Matt. 7:28, 29, NIV). His first lesson is against pride, the haughty attitudes of the priest and Levite that made them superior to other humans. Proverbs 16:5 teaches important truth: “The Lord detests all the proud of heart. Be sure of this: They will not go unpunished” (NIV). In their self-exaltation the religious leaders despised even people of their own nation, regarding them as of lower status.

They despised Jesus, too. His origins were a strike against Him (John 1:46). Also, He did not follow their example of shunning some of His own people. Instead He mingled with them—harlots, publicans, and sinners—“as one who desired their good.”1 The leaders’ pride did not allow them to understand His great mission of mercy to all of humanity. They had crafted a righteousness of their own that set aside God’s standards. They taught His holy law, but it was not in their heart to obey its divine principles. Jesus taught: “The teachers of the law and the Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat. So you must be careful to do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do” (Matt. 23:2, 3, NIV). Their spiritual leadership was not worth following.

The example of secular leadership was no better. Indeed, the story of King Herod Agrippa I, a decade after Jesus, makes for a major illustration on the disaster that pride is.

Herod Agrippa I was very angry.2 The text doesn’t say why, but it does indicate with whom— with the people of Tyre and Sidon, Phoenicians living along the Mediterranean sea coast north from Judea (Acts 12). The people of that region had their own proud heritage of marine skills and trade, fine earthenware, colonializing North Africa, and respected cultural stature.

At the start of the short Bible story (Acts 12:20-23) King Herod is still feeling embarrassed at Peter’s recent escape from prison. Perhaps the king thought that he had found a positive way to release his frustrations. He tried to handle a “furious quarrel”3 with a great speech that would safely inflate his pride while winning the argument with the Phoenicians. This would be better than some act of vicious vengeance against them. So he dressed in his royal robes one day, went to the place of his appointment, sat in the seat of importance, and spoke to the people. Whether it was the beauty of his voice or the quality of his language, his eloquence overwhelmed the crowd, all the more, perhaps, because he had chosen nice tones or sweet speech for them instead of cruel acts against them. The crowd began to shout, “The voice of a god and not of a man!” (Acts 12:22). In a moment the king forgot—if he had ever known—the principle that pride precedes destruction. Flattered by the praise, he absorbed the glory he thought was his own. “Immediately, because Herod did not give praise to God, an angel of the Lord struck him down, and he was eaten by worms and died” (verse 23, NIV). The Lord does not cooperate with human pride, whether it be with politicians to their public, or preachers in their pulpits: “God opposes the proud but shows favor to the humble” (1 Peter 5:5, NIV).

The second lesson taught by our Master in this parable is closely related to the first. His last word to the lawyer in regard to the Samaritan, “Go and do likewise,” was a rebuke to the neglect that would let anyone bypass a wounded person, any victim in need of help. Pride may not be a visible marker, but its residence in the mind is revealed in word and action. The special lament of this story is that it involves religious leaders whose own Bible or Torah teaches that vulnerable people must be cared for.

According to the book of Leviticus, their harvest should leave grain for the poor; the disabled deserved their care, not their mockery, nor becoming objects of ridicule; their legal judgments were to be fair to poor and rich (see Lev. 19:9-15); they were to show respect to the elderly (verse 32). Particularly relevant to Jesus’ story about a foreigner, they were to be kind to strangers, remembering that they themselves used to be strangers (verses 33, 34). They were to be protectors of orphans and single women, and give their loving care to foreigners (Deut. 10:18, 19). Ignoring sufferers in their suffering was not part of their training. It should not have been part of their practice.

Our third lesson is the truth that the condition of the heart matters more than the outward appearance or nationality. This same lesson was taught to Samuel the prophet as he inspected Jesse’s sons, in order to choose Israel’s second king. As he was impressed by Eliab, the Lord told him, “Do not consider his appearance or his height, for I have rejected him. The Lord does not look at the things people look at. People look at the outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart” (1 Sam. 16:7, NIV).

The true nature of the mind shows up in the actions, whether good or bad, disobedient or obedient. John the Baptist had a warning for his countrymen who thought they were safe because of their ancestry: “Do not think you can say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our father.’ I tell you that out of these stones God can raise up children for Abraham” (Matt. 3:9).

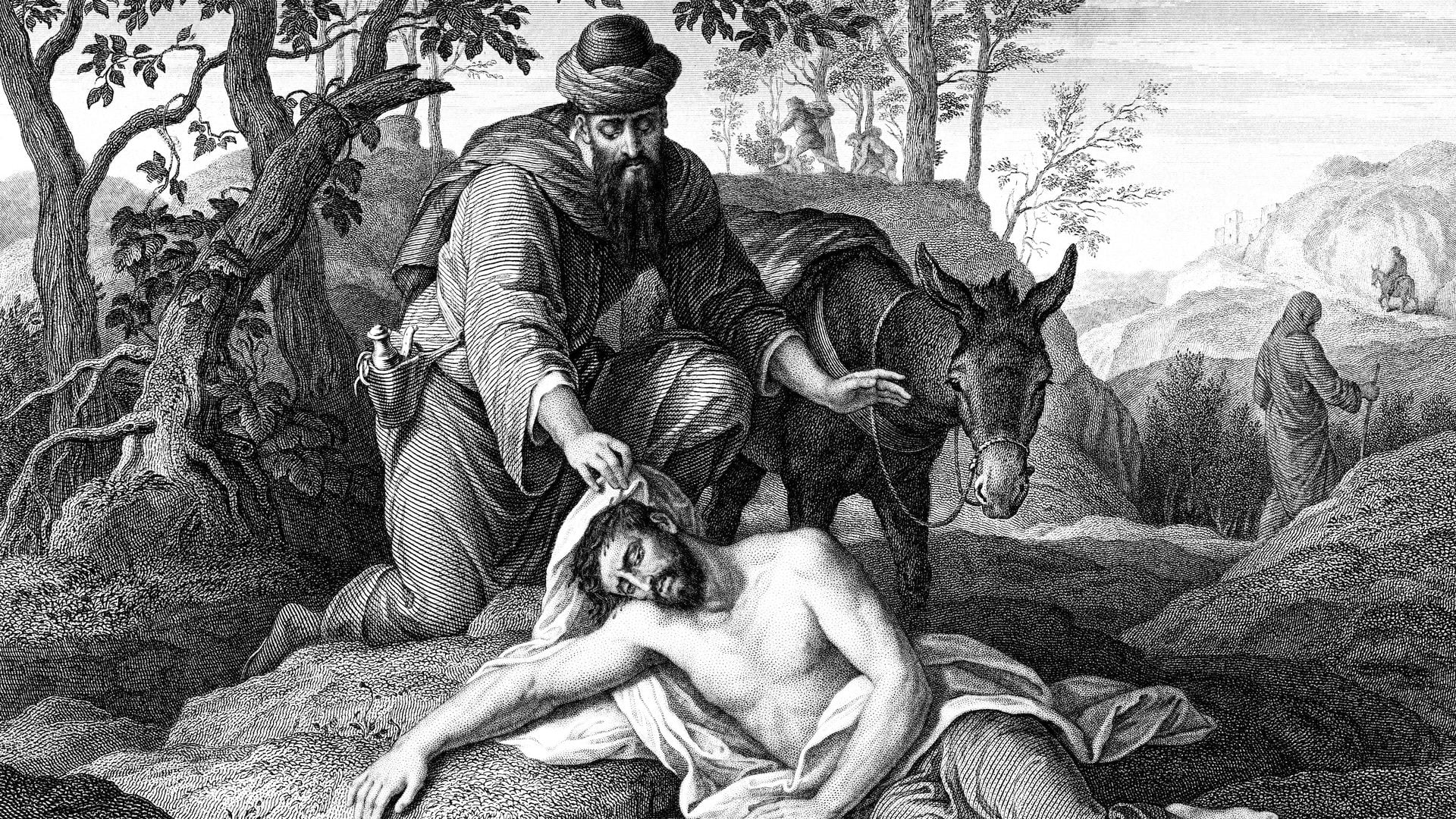

Tax collectors and harlots were looked down upon by their own leaders, even though they were their countrymen and women. Samaritans, Romans, and other nations were despised because they were foreign—heathen Gentiles. But Jesus had no prejudice or hatred for anyone. The good Samaritan exemplified the meek service of His own loving example. When he saw the wounded man on the Jericho road, the Samaritan came closer. As a foreign traveler himself, he did not care if the helpless man was a Jew or a Gentile. All that mattered was that he needed help. Risking danger to himself, alone in a place known for bandit attacks, the Samaritan ministered to the wounded man, put him on his own donkey, and brought him to the nearest inn, where he cared for him through the night. The next day, before continuing his journey, he paid the innkeeper to continue caring for the injured man, promising to reimburse him for any further costs. The Samaritan was a true neighbor.

This fact was plain to the lawyer listening to Jesus’ parable. But prejudice held him in its chains. In answer to Christ’s pointed request to identify the neighbor he could not say, “The Samaritan.” Instead, as we say, he beat about the bush with “He who showed mercy on him.”

The Samaritan, so grudgingly acknowledged, has left us a godly example to follow, as Jesus counsels the lawyer: “Go and do likewise.”

I find it interesting that among all of the parables of our Lord, there is none entitled “The Good Priest” or “The Good Levite.” That a widely known and loved parable of Jesus is called “The Good Samaritan” by Christians today is a testament to the truth of this verse in the epistle of James: “Humble yourselves before the Lord, and He will lift you up” (James 4:10, NIV).

1 Ellen G. White, Gospel Workers (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1915), p. 363.

2 The term thumomachōn occurs only here in the Greek New Testament, providing the only instance in the New Testament where English Bible versions (I reviewed eight of them: ESV, KJV, NASB, NKJV, NET, NIV, NLT, NRSV) say someone was very angry. Evidently this was unique anger: the king had taken exceptional offense at something.

3 An appropriate rendering of the Greek term thumomachōn.

Patricia J. Smith lives in Pioneer, Louisiana, is a second-generation Seventh-day Adventist, and loves to share God’s love through her writing.