The story of Jonah the prophet is undoubtedly one of the most well-known stories of the Old Testament. The book’s plot can entertain little children during Bible readings at home and puzzle biblical scholars poring over the Hebrew text. There is much more in this book than the story of a stubborn prophet swallowed by a big fish. In this article I will discuss two issues related to Jonah’s book, namely, first, God’s plan to reach Nineveh, and, second, the meaning and fulfillment (or lack thereof ) of God’s prophecy in Jonah 3.

The opening words in the book introduce our prophet, Jonah, as the son of Amittai. According to 2 Kings 14:25, Jonah served as a prophet in the court of Jeroboam II of Israel during the first half of the eighth century B.C.1 This chronological information situates the book of Jonah in a crucial period in Assyrian history, the territory in which Nineveh was a prominent city. During the first half of the eighth century B.C., the Assyrian Empire faced several problems, both foreign and domestic. During that time, Assyrian rulers were concerned with the northern borders of their realm, fighting against the kingdom of Urartu. Urartu is known in the Old Testament as the “land of Ararat” (2 Kings 19:37; Isa. 37:38). It encompassed an area that roughly corresponds to modern-day Armenia and adjacent territories of eastern Turkey, northwest Iran, and a small portion of northern Iraq. The sparse information about the Urartian kingdom available until now is mainly from Assyrian archives and royal inscriptions. According to these documents, this nation played a significant political role in the region from the ninth to the sixth centuries B.C. In the first half of the eighth century B.C., the time of Jonah, the son of Amittai, Assyria experienced a period of political instability. The Urartian king Sarduri II took advantage of this weakness and defeated the Assyrian king Ashur-Nirari V (754-746 B.C.). The mighty Assyrians were now a weak polity in the region.

A second problem affected the Assyrians during that time. Mesopotamian scribes registered an eclipse on July 15, 763 B.C., precisely during the time of Jeroboam II and the prophet Jonah. The scholarly community of ancient Mesopotamia treated eclipses as divine warnings to humanity. Many of these astronomical omens were cataloged and became part of an extensive collection of cuneiform tablets known as Enuma Anu Enlil. Some of the interpretations of eclipses in this series have a very dark tone and must have alarmed the Assyrian audience. Here are some examples: “The king shall be deposed and killed, and a worthless fellow will seize the throne”; “The king will die, and rain from heaven will flood the land; there will be famine”; “A deity will strike the king and fire will consume the land”; “The city wall will be destroyed.”2 In other words, there was an intense feeling of uncertainty among the Assyrians. They expected disaster at any moment.

It is against this background that we should read God’s commissioning of Jonah to preach to the Ninevites. The God of the Bible controls history and the universe and is deeply interested in saving not just His people, but “the world.” He used the geopolitics of the ancient Near East and contemporary astronomical events that were so important for the Assyrians to prepare their minds and hearts for Jonah’s preaching. No wonder people were receptive to Jonah’s message, as we find in chapter 3 of his book.

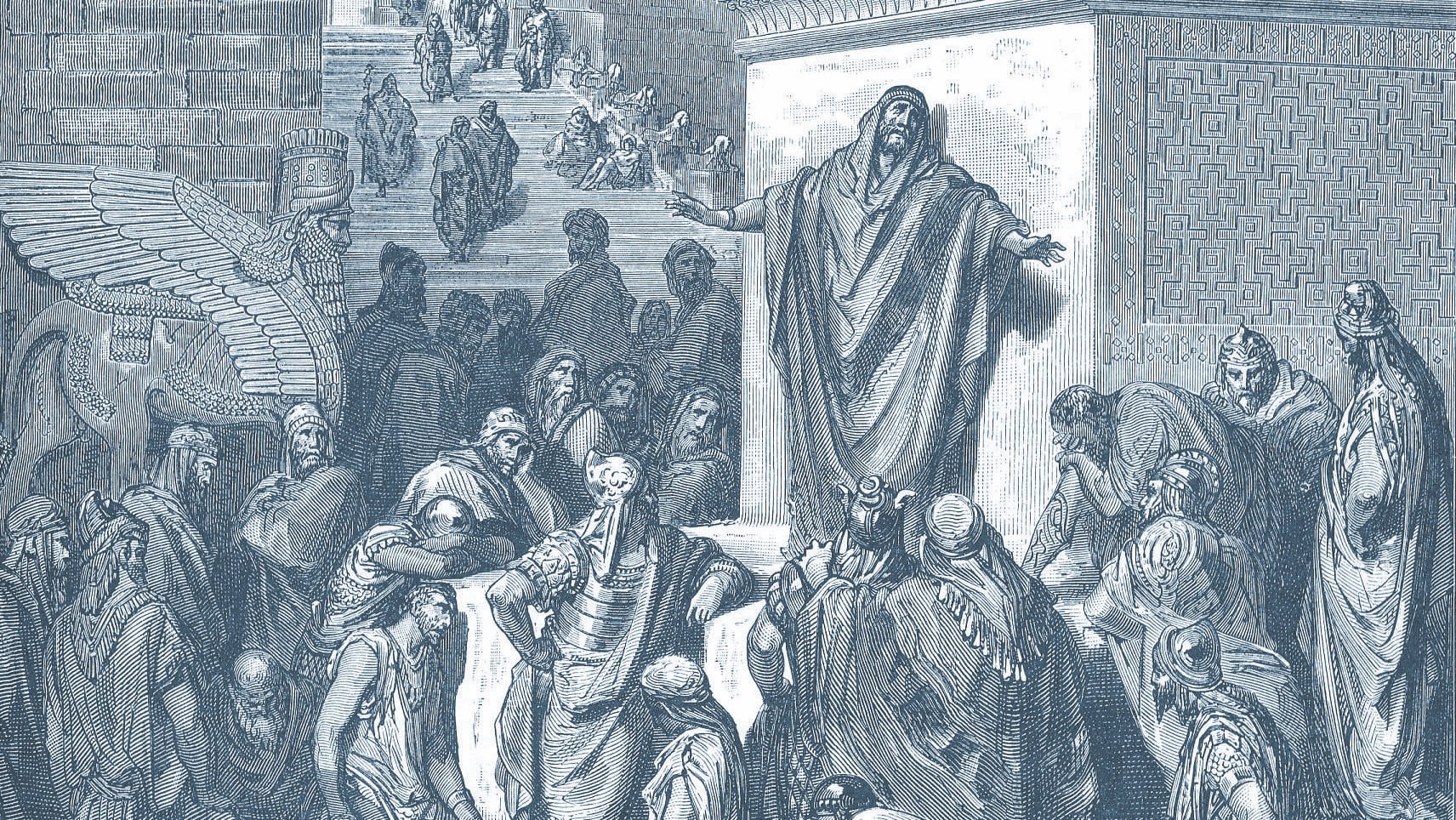

The events described in Jonah 3 are straightforward. After Jonah’s experience in the belly of the fish, God commissioned him a second time to preach His message to the Ninevites (Jonah 3:1, 2). This time the prophet obeyed the divine order and uttered God’s prophetic word to the inhabitants of Nineveh (verses 3, 4). The prophetic message, at least as described in the biblical book, is concise: “Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown!” (verse 4). Consequently, the Ninevites believed in God, and the ruler of Nineveh instituted several external signs of repentance (i.e., fasting, sackcloth) among the population (verses 5-9). When God saw how the Ninevites turned from their evil ways, He changed His mind about the punishment He intended to inflict upon the city.

To solve the apparent problem of God changing His mind and Jonah’s “failed” prophecy, we explain this divine decision with such texts as Jeremiah 18:7-10. In these verses God explicitly tells Jeremiah that He conditioned some of His prophecies according to an audience’s actions and reactions when receiving such a message. While this is true, we should be cautious in saying that Jonah’s prophecy did not come to fruition. Even though his message to the Ninevites is short (Jonah 3:4), it has a deeper meaning than we often recognize. What did Jonah mean when he says, “Nineveh shall be overthrown”?

The Hebrew verb translated here as “overthrow” is hapak, a term repeatedly used to describe divine acts of destruction and judgment. For example, the verb hapak is used to describe God’s destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (Gen. 19:21, 25; Deut. 29:22). Isaiah and Jeremiah compare Babylon’s destruction to what God did (hapak) to those two cities (Isa. 13:19, 20; Jer. 50:39, 40; see also Jer. 49:17, 18). The prophet Zephaniah also invokes the divine action against these two cities when describing the punishment that will come upon Moab (Zeph. 2:9). There is no doubt that hapak indicates destruction. But this is not the only meaning of the verb hapak. The same verb is used to describe what God did to the waters of the Nile river, “turning” (hapak) them into blood (Ex. 7:17, 20), and the sun “turning” into darkness (Joel 2:31). This is also the same verb used to describe God’s emotions with regard to Israel in Hosea 11:8, moving from judgment to compassion. Finally, hapak is used to describe the change in Saul’s behavior in 1 Samuel 10:6 and 9. In this passage the newly appointed king of Israel receives the Spirit of God and is “turned” (hapak) into another man.

Thus, God’s prophecy to Jonah had a double meaning. It pointed both to the potential destruction of the city, while at the same time also referencing the possible transformation (or “turning”) of the Ninevites.

Should we understand this as a “failed” prophecy? It depends on whom you ask. Jonah, based on his mindset that becomes visible in his dialogue with God, would most likely have answered yes, since he anticipated the first meaning of hapak, namely destruction (Jonah 4:1-5). But God would answer no. The Ninevites did change their behavior and turned from their evil ways, as indicated in the second meaning of the verb hapak.

These comments about the book of Jonah should remind us that God controls history, and He can use, to His purposes, world events we deem as insignificant. Furthermore, when we talk about end-time prophecies, we should be careful with dogmatic positions regarding their fulfillment. Instead, intellectual modesty and spiritual humility are warranted. As Jonah, some of us might expect the unfolding of end-time events in a particular way, and yet God may act in a manner that will catch many of us off guard. God will bring these prophecies to fruition—even if He is doing it in unexpected ways that may surprise us.

1 The reign of Jeroboam II has been dated 782-753 B.C.

2 Donald J. Wiseman, “Jonah’s Nineveh,” Tyndale Bulletin 30 (1979): 46.