The Seventh-day Adventist Church was organized in the midst of the American Civil War, a conflagration sparked by slavery that raged for four years.

At the Birth of a Church

Though the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation officially abolished slavery in the rebel states, millions of Blacks living in the United States had to contend with situations and conditions after slavery that mirrored what enslaved Blacks experienced during the “Diabolical Institution.”

Many Adventist pioneers spoke out against slavery, among them Ellen G. White. The Adventist Church founder categorically and vehemently condemned slavery, going so far as to encourage Adventists to disobey legislation that denied slaves their God-given rights. White was a reliable and staunch ally of those who stood up for the oppressed, believing that to do so was in alignment with the life and teachings of Jesus Christ.

In spite of the racial solidarity demonstrated by Ellen G. White and other Adventist Church leaders, the African American experience in Adventism was not without challenges. Race remained a vexing issue in America throughout Reconstruction and Jim Crowism, taxing America’s dream of equality for all people, especially those of African descent. Not surprisingly, the challenges and issues that race triggered in the broader society were mirrored in the Seventh-day Adventist Church as it struggled to respond meaningfully to the biblical call to embrace all humankind.

As the twentieth century dawned, Adventist Church leaders established another layer in the organizational structure of the denomination called unions. Intended to ward off Jerusalem centers that too often contribute to, if not result in, autocratic leadership, union conferences were followed in 1922 by world divisions of the General Conference. Yet the organizational issue that towered in significance in America, in the early twentieth century, was not the lack of servant leaders in the church, but the race issue. People of African descent continued to struggle for full acceptance in the denomination, their faithfulness to Adventism notwithstanding.

Histories of the Seventh-day Adventist Church have not yet adequately noted the African American experience in Adventism. Though that experience and story are not always rosy, they still need to be told. If nothing else, they are instructive and should contribute to crucial conversations that, hopefully, will contribute to transformation and growth.

Histories of the Seventh-day Adventist Church have not yet adequately noted the African American experience in Adventism. Though that experience and story are not always rosy, they still need to be told. If nothing else, they are instructive and should contribute to crucial conversations that, hopefully, will contribute to transformation and growth.

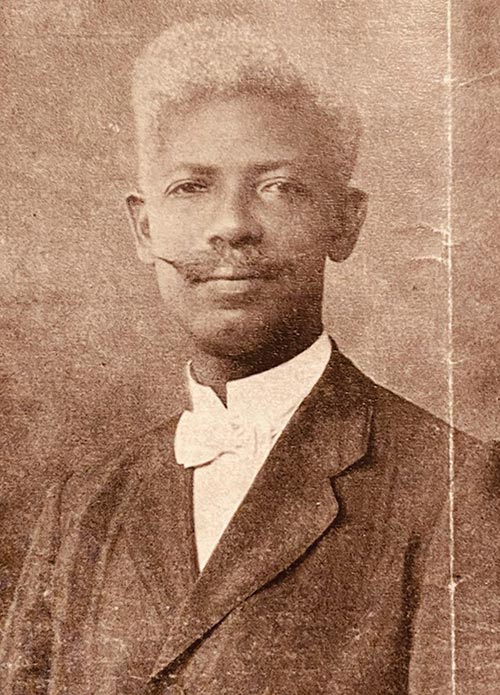

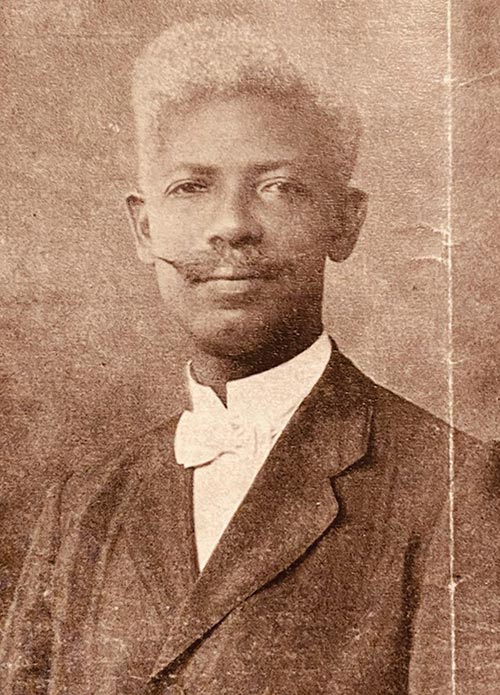

Among the outstanding Black Adventist leaders in North America in the early twentieth century was James Kemuel Humphrey, whose story is not well known in spite of the key role he played in the establishment of regional conferences in the North American Division. Yet Humphrey’s life and legacy provide a window into early-twentieth-century Adventist history and form a link that is crucial to Adventism’s unique self-understanding and journey in dealing with the issue of race.1

James K. Humphrey was a Jamaican national who stopped in New York City on his way to visit Africa from the West Indies. Humphrey stumbled upon an evangelistic series in Brooklyn, New York, one day, and was struck by the simplicity and force of what he heard. Though he was a Baptist minister, he immediately embraced the Seventh-day Adventist message, aborting his trip to Africa as a result.

Humphrey was tapped to lead the small group that resulted from the evangelistic series and, in large part because of his leadership skills, was a standout among the ministers in the Greater New York Conference by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century. He was appointed to the executive committee of the Negro Department of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists in 1909, and as a delegate from the Atlantic Union to the General Conference Session in 1913. Humphrey conducted several tent crusades throughout the 1910s, and the result was that by 1920 First Harlem, which Humphrey was pastoring, boasted a membership of 600.

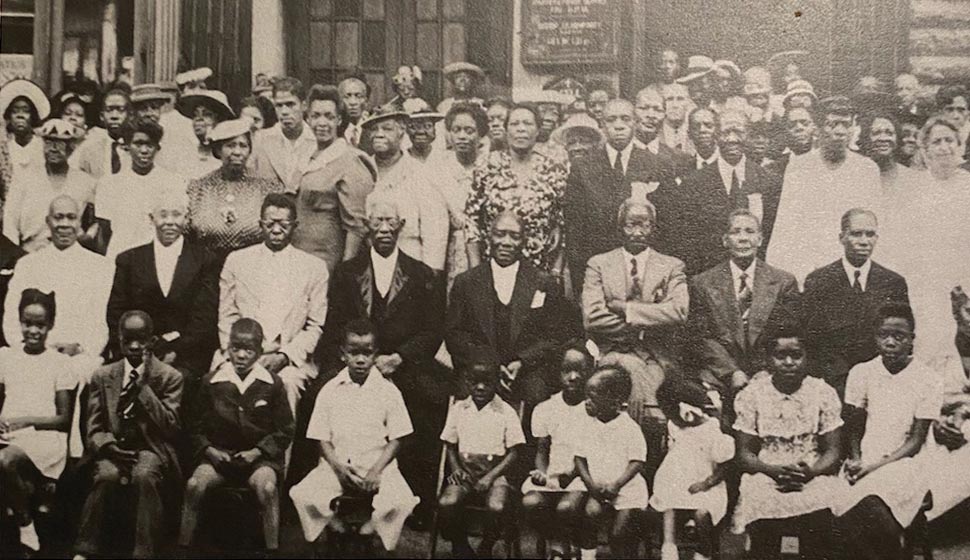

By the end of 1922 there were four African American congregations in the Greater New York Conference, all under Humphrey’s supervision. First Harlem grew so exponentially that it spawned Harlem Number Two by the middle of the “Roaring Twenties.” On every hand and by every measure, James Kemuel Humphrey was a minister of rare ability whose giftedness was recognized and appreciated by his peers and denominational leaders. His counsel was sought and embraced for its logic and depth.

His epochal ministerial tenure was not without its challenges. The pastor was prone to share his physical struggles and, on a couple occasions, petitioned church administrators to be relocated from New York City. Denied both times, Humphrey made it clear that he was struggling with the race issue and that it was a thorn in his side. As early as 1905 he had been lobbied by an African American minister who was contemplating severing ties with the denomination to join him. In spite of Humphrey’s unhappiness with the state of race relations in the Seventh-day Adventist denomination, he refused to break with the denomination at that time, or for several years thereafter,2 claiming that Adventism was God’s organized plan to bring the message of salvation to the whole world.

Humphrey chose to share the information about being asked to join another African American minister in breaking from Adventism during a sermon he preached at the General Conference Session in 1922. Entitled “The Divine Program,” the sermon was more gripping personal testimony than biblical exposition of 1 Peter 5:10 (God will help after you’ve suffered for a while). Humphrey bemoaned the independent church movement, asserting that those who severed ties with the established church were, almost exclusively, disaffected recalcitrants out to make a name for themselves. He vowed to remain faithful to the Adventist denomination, saying that, in the end, Jesus Christ was fundamentally more significant than any organization or personality. His own salvation was of paramount importance to him, as was evangelizing everybody whom God had entrusted to his care.

Throughout the 1920s Humphrey’s commitment and dedication to Adventism held firm. Serving in Harlem was both invigorating and motivating. Harlem was in its heyday as the Black capital of the United States. Located on the northern tip of Manhattan, Harlem had evolved from being a sleepy village to being the locus for the Black cultural awakening known as the Harlem Renaissance. The area attracted Blacks from the South as well as from the West Indies and was home to just about every social and political Black organization in the country.

Humphrey was among the first wave of immigrants who came to New York City from the West Indies. That population started coming in significant numbers around 1900 and continued to do so until the nation’s immigration laws changed in 1924. The complex web of likes and dislikes that initially characterized the relationships of West Indian immigrants and Blacks born in the United States quickly dissolved in the face of their unified social vision.

As the “Roaring Twenties” neared their end, the First Harlem Adventist Church, which Humphrey was leading, was the largest Adventist congregation in New York City and one of the largest in the United States. Humphrey’s frustration with race relations in the denomination was increasing, though, and would soon reach a breaking point.

1n 1928 William H. Green, a brilliant Black lawyer from Detroit who had led the Negro Department for the previous decade, passed away. Humphrey attended Green’s funeral, presided

over by General Conference president W. A. Spicer, who delivered the eulogy. Humphrey was one of three individuals who authored Green’s obituary. Green’s death created an opening in Black church leadership, which Black church leaders sought to fill by calling for the creation of regional conferences, a concept that had been mentioned and advanced years earlier by Charles H. Kinney, the “Father of Black Adventism.”

Black church leaders believed that the Negro Department of the General Conference was largely ineffective and that regional conferences would be infinitely more effective in delivering on the mission to reach people of color. The call for the establishment of regional conferences met with emphatic resistance and was voted down by the 18-member special committee impaneled to consider the request. Humphrey was one of the committee’s six Black members, who were particularly chagrined when they were admonished never to raise the issue of regional conferences again.3

Shortly thereafter, Humphrey began to promote an independent business venture among the members of his Harlem congregation. The venture, called the Utopia Park project, would be a commune located outside of New York City where African Americans would experience a measure of self-determination in the pursuit of Adventism’s wholistic mission.4

When church leaders got wind of the project, they sought to engage Humphrey in conversation about it. A flurry of written correspondence was exchanged, and Humphrey was invited and encouraged to personally share with the executive committees of the Greater New York Conference and Atlantic Union the details of his plans. He rebuffed church leadership, and in January 1930 his ministerial credentials were revoked and his congregation, which voted 595 to 5 in support of him, was expelled from the sisterhood of churches of the Greater New York Conference.

His break with the Seventh-day Adventist Church final and irrevocable, Humphrey established a Black, independent religious organization called the United Sabbath Day Adventists, which flourished for a while in North America and in parts of the West Indies before disintegrating around the end of the twentieth century. Humphrey himself gave up leadership of the organization in 1947, five years before his death, and his last days are shrouded in uncertainty, conjecture, and suspicion. That he became legally blind toward the end of his life is almost certain.

Unable to reconcile Christianity’s emphasis on love and inclusion with what he considered the discriminatory practices of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Humphrey concluded that the time was ripe for African Americans to establish their own organizations. Humphrey did not have any doctrinal differences with the Seventh-day Adventist denomination. In fact, United Sabbath Day Adventists continued to mirror Adventism in how they understood mission and engaged in ministry. They studied the Sabbath School lessons [Adult Bible Study Guides] used by Seventh-day Adventists and structured their denomination as Seventh-day Adventists do. As Humphrey would tell it, he founded the United Sabbath Day Adventists because of the treatment people of color experienced in the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Doctrinally, Humphrey was a Seventh-day Adventist to the end.

Not many Seventh-day Adventists are familiar with James Kemuel Humphrey or the denomination he founded, and even among the few who know this episode of our church’s history there is uncertainty about Humphrey’s life and legacy. Yet James K. Humphrey and the United Sabbath Day Adventists form a critical link in the history of race relations in the Adventist Church. His bold break was the most noteworthy of those by prominent black leaders who severed ties with the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the early twentieth century over the treatment of Blacks.5 Humphrey was viewed by those who broke with him and supported him as a courageous pioneer, and many contend that the true beneficiaries of Humphrey’s split with the Seventh-day Adventist denomination are African Americans who subsequently joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church.6 Humphrey’s break, as well as others, may have created a barrier to winning Blacks to Adventism. But it did not last.7

R. Clifford Jones, dean of Oakwood University’s School of Theology, is author of James. K. Humphrey and the Sabbath-Day Adventists, available from University Press of Mississippi.