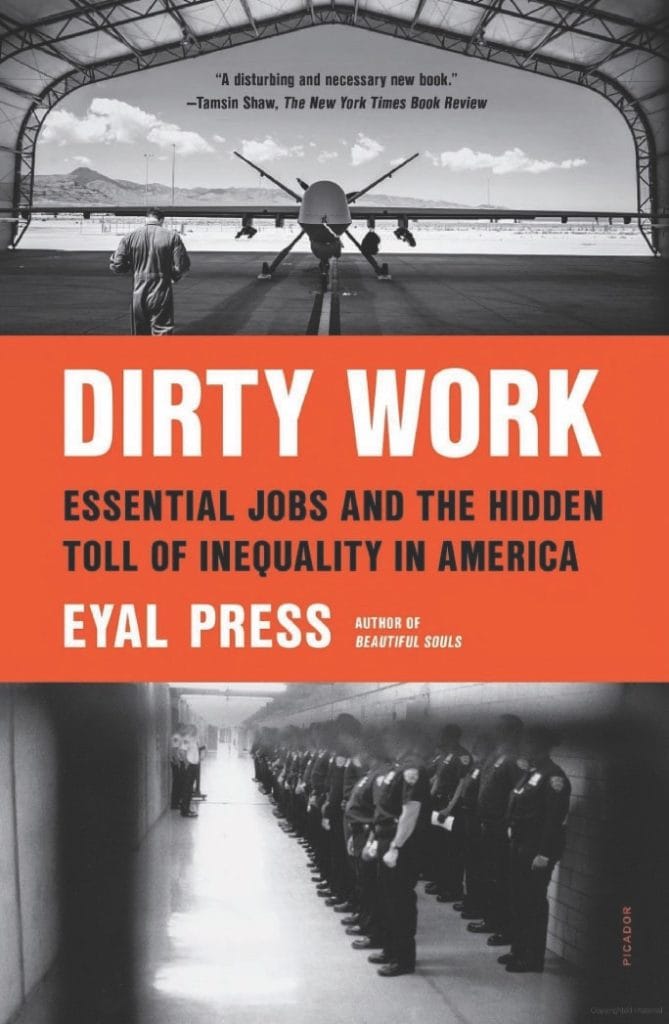

Eyal Press has published another book on mental decency. But unlike with Beautiful Souls: Saying No, Breaking Ranks, and Heeding the Voice of Conscience in Dark Times (New York: Picador, 2012), he does not here focus on our better angels. Instead he writes on displaced morality, on its scope; on its disconcerting pervasiveness; on its apparently compellingly sinister inevitability.

His resulting work is now acclaimed as one of the 10 best books of 2021 and has been awarded the 2022 Hillman Prize for Book Journalism.

The book’s nine chapters, organized into four parts, deal with matters concealed “Behind the Walls,” “Behind the Screens,” “On the Kill Floors.” Finally, and dismayingly, they deal with the essential character of such concealment to “The Metabolism of the Modern World.” Chapter headings such as “Civilized Punishment,” “Joystick Warriors,” “Dirty Energy,” and “Dirty Tech” offer some statement on the range of his meddling. Most telling of all titles, perhaps, is his seventh, where quotation marks ensure that the reader is not confused as he writes about “Essential Workers.” An epilogue of six pages, acknowledgments occupying two more, and 17 that index key words, names, and phrases bring up the rear.

Aware of the implications of his work for the world, Press introduces his book with, and presents it under a borrowed and telling epigraph, words of American writer and activist James Baldwin: “The powerless must do their own dirty work. The powerful have it done for them.”

Press rejects equating Nazi German terror with life in any democracy. But he acknowledges a debt to American sociologist Everett Hughes for (1) his reports of conversations with sophisticated, intellectual, mid-twentieth-century Germans; and (2) his highly appropriate phrase, “Dirty Work,” which titles this book, Press’s third. His observations, analysis, and reportage range from seemingly intractable abuses present in America’s prison system to the elegance of remote-control conflict in a war room 7,000 miles away from the dying—guilty or other—if not the killing.

During a semester of teaching abroad in 1948, Hughes sipped tea and chatted about science and the fine arts with German scholars and professionals who were neither uniquely authoritarian, nor distinctly fanatical, nor peculiarly cruel and discriminatory. They could have been colleagues of his from any enlightened Western nation. Hughes was rebuked for thinking thus and saying so in America, Press advises. And it took him significant effort to make clear to whom his scholarly writing on the matter was directed: “I do not revive the case of the Nazi Endlösung (‘final solution’) . . . to condemn the Germans.” His actual intent was “to recall to our attention dangers which lurk in our midst always.”

In Dirty Work Press demonstrates how perilously invested American societal structures, and we its soldiers and social workers, meat packers, and oil pipeliners, all are in dirty work; how we’ve consigned it to relative obscurity, away from the public eye, but with adequate public consciousness of its ugliness and shame, and why we find it better thus.

By anecdote and incisive reflection Press repeats a single, disturbing question, for whoever will hear it. How moral are you after all? There is no doctrinaire force to Press’s effort—only a profound conscientiousness that cannot leave the reader unaffected.

How marvelous to hope that Dirty Work may be the first step of many toward a cleaner conscience.