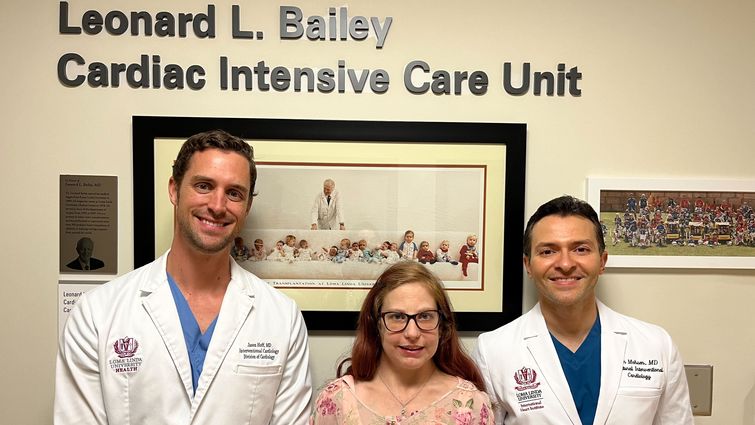

Thirty-two-year-old Colleen Barber has partnered with care teams at the Loma Linda University International Heart Institute longer than she can remember — from the time of receiving a heart transplant as a baby to recently undergoing a minimally invasive procedure to close a hole called an atrial septal defect (ASD) in her transplanted heart.

Structural interventional cardiologists Jason Hoff and Amr Mohsen frequently team up to perform heart procedures that involve repairing or replacing valves and treating other structural abnormalities like holes in the heart. What made Colleen’s procedure unique was that it was performed on a transplanted heart, Hoff says, which presents different anatomical considerations than a native heart.

“It’s special because Colleen has been part of the International Heart Institute family for a long time,” Hoff says. “It’s been a lifelong journey for her, so to be a small part of that journey is a blessing.”

Colleen was born in Texas in 1990 with hypoplastic left heart (HLH) syndrome, a rare congenital heart defect in which a severely underdeveloped left side of the heart is incapable of supporting systemic blood circulation or supporting life. Hoff says that babies with HLH must receive a transplant to survive.

Colleen’s mother, Pam, says she heard of the high-quality transplant care at Loma Linda University Medical Center, where world-renowned heart surgeon Leonard Bailey practiced. Pam traveled to Loma Linda for her baby’s transplant within the week. At 19 days old, Colleen received a new heart transplanted by Bailey.

“My daughter is a rock star,” says Pam, who sang the lullaby “You Are My Sunshine” to her daughter throughout her hospitalizations. “She is beautiful, she is wonderful, and she is my sunshine.”

Hoff says the heart Colleen received was so small that it would have been difficult at the time to detect any shunts — passages by which blood moves in a pattern that isn’t normal. It’s likely that as her heart grew, the hole became more prevalent over time, he says. ASD, a hole between the two top chambers of the heart, causes abnormal blood flow and places extra strain on the right side of the heart; this can lead to heart failure and pulmonary hypertension.

Colleen has been following up with heart care teams since her transplant. Routine surveillance imaging first revealed the ASD roughly a decade ago, when the hole was small and not causing heart damage. Transplant and heart failure specialists Liset Stoletniy, Diane Tran, and Antoine Sakr tracked the ASD until the hole threatened negative impact on Colleen’s transplanted heart. They then referred her to structural interventional cardiology, where Hoff and Mohsen reviewed her echocardiograms with Ramesh Bansal, who has performed her imaging studies since she was a baby. Together they decided they could fix the ASD in a minimally invasive way rather than pursue an open-heart surgical route.

To perform the procedure, Hoff and Mohsen made a small puncture in a leg vein and used live, high-quality imaging to maneuver a thin tube called a catheter up the vein to Colleen’s transplanted heart, which is positioned differently in the body than a native heart. The procedure was guided with real-time 3-D transesophageal echocardiographic imaging conducted by Bansal. Once the catheter reached the hole in Colleen’s heart, Hoff and Mohsen deployed an ASD closure device that used two disks to sandwich either side of the hole. From there, Hoff says, the body can create a new lining over the disks, closing the gap.

Colleen says the procedure felt seamless, and she experienced minimal discomfort in recovery. She returned home the next day and now, three months later, continues her rhythm of life. She is an avid reader and enjoys spending time with her friends and boyfriend, who is also the recipient of a heart transplant. She owns two dogs and a cat and plans to attend school to pursue a profession that allows her to work with animals.

“I’m very grateful that the heart care team found the hole and were able to fix it,” she says. “This isn’t the first time they saved my life.”

Hoff says that the fast-growing, dynamic field of structural cardiology enables treatment options that patients may not have had before.

“If you were previously told nothing could be done for your heart from a structural standpoint, you should consider coming to a place like the International Heart Institute that offers the full spectrum of cardiac care, from new advances in open heart surgery to minimally invasive robotic repairs and transcatheter technologies,” he says.

Hoff says Loma Linda University’s structural heart program takes pride in a team-based approach, where structural cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons work together to find the best treatment options for each patient. “This process is critical to finding the right solution for each and every patient, because each patient’s case and treatment is unique,” he says.

The original version of this story was posted on the Loma Linda University Health news site.