The Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists (ESDA) is now live and freely accessible at encyclopedia.adventist.org. Launched Wednesday, July 1, at the Seventh-day Adventist Church headquarters in Silver Spring, Maryland, United States, the project involves nearly 1,000 writers from all world church divisions and attached fields, and features more than 2,100 articles, photographs, and other historically significant documents. New articles will continue to be added to the encyclopedia. We invite you to visit encyclopedia.adventist.org for education and insight on the history and structure, culture, theology, and more of the Adventist Church around the world. The following story is based on a longer article from the encyclopedia.—Editors.

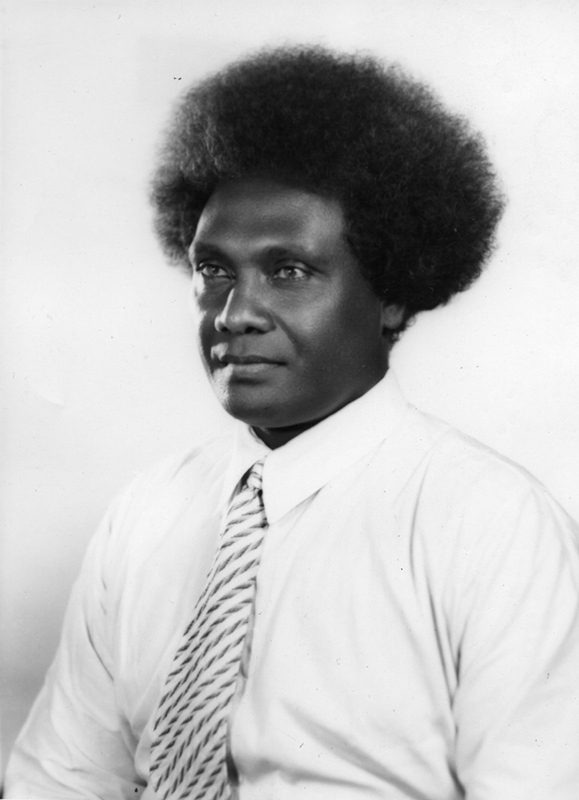

Of all the clans in the Solomon Islands, the Marovo Lagoon tribesmen were once considered the most warlike and cannibalistic. In 1902, the Marovo chief, Tatagu, led a fishing expedition. He disregarded the devil-fear that the islanders adhered to and did not affix to his canoe a vine, or “string.” The string was supposed to appease the devil and bring a good catch. After three fruitless days, the tribesmen were about to rebel when Tatagu spied a large school of fish. Returning home in triumph, Tatagu learned that a son had been born to him. Following a local custom of naming progeny after the most important current event, Tatagu called his baby Kata Ragoso, meaning “no devil strings.”1

In his early years, Kata Ragoso saw his people worshipping their ancestors’ spirits. He also saw his father frequently leading intertribal warfare and headhunting raids. The warriors put the heads of their defeated enemies in the skull house as signs of power and victory.

While Kata Ragoso was growing up, unprincipled white traders came to the Solomon Islands. They brought cloth, steel axes, and bright trinkets. Young Ragoso witnessed many people being enticed into the holds of the ships with pretty beads and trinkets and then taken away as slave laborers.

When Kata Ragoso was about 12, a small white boat, the Advent Herald, came into Marovo Lagoon. When the boat dropped its anchor, Ragoso’s cousin Pana was playing on the beach with some other boys. Captain Griffiths F. Jones came ashore and asked for Chief Tatagu, so Pana took him to where the chief was tending his garden about three miles away.

Jones requested land on which to build a school, and Chief Tatagu eventually agreed. Ragoso was one of the first students to attend the school. Subsequently, he accepted Christianity and was one of the first Solomon Islanders to be baptized.

Ragoso learned to speak and understand English. He observed the leadership methods of the Europeans and adapted them to his cultural setting.

In 1935, Ragoso was appointed as assistant to the superintendent of the Solomon Islands. The next year, he attended the 43rd General Conference Session in San Francisco, California. While in the United States, he had planned to speak in the Marovo language and be translated by Norman Ferris. At the beginning of the session, however, Ferris fell ill. The General Conference leaders suggested that Ragoso make his best effort to speak in English for his presentations. He was hesitant, but after praying about it, agreed to try. Those who heard him viewed it as “a modern miracle—the bestowing upon this humble faithful servant of Heaven the gift of tongues.”2

During World War II, all expatriate personnel returned to their homelands, and Ragoso was left in charge of the Seventh-day Adventist work in the Solomon Islands. He led his people to build storehouses in the bush in which to hide the mission equipment. They also camouflaged the mission boats so they could not be seen from airplanes

Then Ragoso posted watchmen to watch for planes or boats being attacked and going down. When these watchmen reported an incident, Ragoso sent men to find and rescue survivors. They took the survivors to military outposts, where they radioed for a rescue plane. Ragoso and his men rescued 27 American pilots and saved 187 soldiers from Australia and New Zealand whose warship had been torpedoed.

How wondrous the work of Christ in the heart of this man raised in a headhunting culture to lead him to organize missions of mercy to rescue foreign troops!

1 Wilson Gia Liligeto, Babata, Our Land, Our Tribe, Our People (Suva, Fiji: IPS Publications, 2006), pp. 40, 41.

2 Editorial comment in Kata Ragoso, “Solomon Island Witnesses,” Youth’s Instructor, July 29, 1947, p. 3.