Exactly 145 years ago the first missionary family was officially sent from the U.S.A. to Europe. Since then thousands have left the comforts and familiarity of home, have overcome culture shock, and have served around the world. They still go!—Editors.

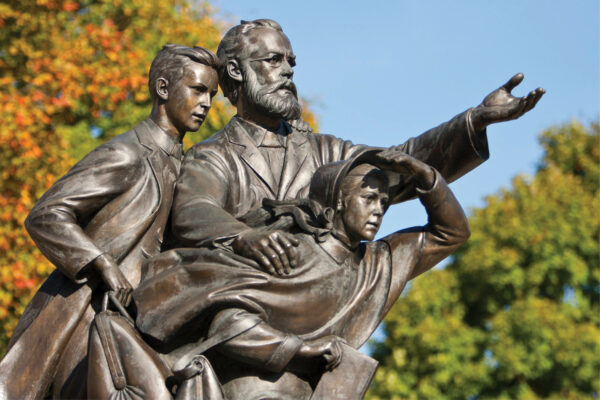

When esteemed church pioneer John Andrews left New York in September 1874 bound for Switzerland with his two teenagers, Mary and Charles, the Adventist Church entered a new era, an era of worldwide mission. Crossing this Rubicon wasn’t an easy decision. Church leaders went back and forth about the need for a foreign mission presence for more than a year before deciding to procede.

Andrews had been an invaluable partner to James White, much as Philip Melanchthon was to Martin Luther. He was the scholarly “systematizer” of Adventist theology. Could he be spared? On the other hand, the ailing James White sometimes saw Andrews as a challenge to his own leadership. Was widower Andrews really the best person to send, even if he could read French?

George Butler, General Conference president, helped crystallize the decision and Andrews’ departure heralded a bright new dawn for the church, although during the morning of that new day cloudy mists often dimmed the light. Problems of finance, health, and cultural misunderstandings abounded.

Innocents Abroad

Andrews had expected certain things to fall into place when he arrived in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, the charming lakeside city that was to be the location of his new life as a missionary. Plans called for the scattered Sabbathkeepers, converted by independent preacher Michael Czechowski a decade earlier, to provide evangelistic helpers and fund the operation.

Andrews himself did not receive a salary from the General Conference; he was supposed to quickly win new converts who would pay his salary. Becoming self-sustaining was the immediate objective.

Battle Creek paid for his passage across the Atlantic, but Andrews had to pay for 13-year-old Mary and 16-year-old Charles, and for the transport of his books and personal effects. Church policy for mission appointments did not yet exist. Andrews had to draw deeply on his personal financial resources to survive.

Upon his arrival Andrews found things very different from his hopes and expectations. Within days the chilly blasts of culture shock almost knocked him off his feet. The national workers he had been counting on were unavailable, and the Sabbathkeeping families were in deep in their own financial difficulty. Funding a salary was not going to be easy.

So much else was different too: the food, the bathrooms, household appliances, local customs. The United States was so much “better” than Europe, so much more advanced, he opined—not always to himself. He didn’t know, of course, to call it “culture shock” at the time, but like every missionary who has followed him since 1874, this was his first challenge. It took months for Andrews to appreciate that differences were just that—not better or worse, just different.

Plain-speaking

An early major adjustment Andrews had to make concerned his penchant for “plain speaking.” A deeply engrained New England custom nurtured in him by mentors James and Ellen White, this style of communication valued honesty and frankness above diplomatic niceties. Communicating with Swiss believers in this way did not go well. His hearers just thought him harsh, insensitive, and antagonistic. It took time for Andrews to adapt, and for Swiss believers to appreciate revivalist-style Adventist social meetings with their distinctive emotional approach to religious experience.

Learning the local language became an important priority for Andrews. He could read French reasonably well, if rather slowly. Speaking it fluently was another thing altogether. He had to learn to speak. Local Sabbathkeepers spoke their French quickly, running their words together in “a low indistinct tone.” Not comprehending, Andrews felt stranded. He experienced agonized exasperation as he struggled to learn. At the age of 45 his tongue and palate would just not shape the sounds his brain intended.

Fortunately, his teenagers, with their much more pliant brain structures, picked up the language more easily. It took three years of stubborn determination for Andrews to master spoken French enough to preach publicly without embarrassment. He learned to converse with some clunky German, but he always needed a translator for preaching. As language specialist Pietro Copiz has pointed out, Andrews’ reputed language abilities accumulated some myths over the years. He wasn’t really such a grand linguist. But he was totally committed to learning what he needed in order to be successful in mission.

With determined effort Andrews eventually mastered the intricacies of written French to such a degree that he was able to launch a quality evangelistic monthly he called Les Signes des Temps (The Signs of the Times). The culturally different and complicated postal system eventually yielded its secrets through trial and error, and the magazine soon reached across borders and cultural boundaries into French-speaking homes throughout Europe and in parts of the world where evangelists could not venture.

Andrews found that American-style evangelism just did not work well in Europe. Preachers had to apply for state licenses in each new locality. Tents were neither safe nor suitable. Halls were expensive and tight-knit villages bound by strong church-state connections were culturally resistant to a religion based in the United States.

It took some time for leaders in Battle Creek to realize that things could be so different. In the interim Andrews was misunderstood and had to face mistrust and a loss of confidence from fellow believers for a time. Not until those in Battle Creek came to Europe to see for themselves did they realize why growth could be slow, and how mission had to be adapted to local culture and circumstances.

The Larger Legacy

John Andrews had a gift for scholarship. His very effective defense of the seventh-day Sabbath in his classic book History of the Sabbath (1861), was highly valued by pastors and evangelists, as were his writings on other distinctive Adventist teachings.

Andrews’ role as General Conference president when James White was ill, and his contribution as editor of the Advent Review and Sabbath Herald through difficult times, also made an enduring contribution.

But his most notable contribution was made in the crucible of the church’s first venture overseas. Andrews learned to be successful in mission though trial and error, and by learning to adapt to new cultures. As he learned, he also helped the church learn. Over time a more adequate policy framework made things easier financially. Finding new pathways to mission was a contribution for which the church will always be indebted to Andrews—its first official overseas evangelist.