The year 1868 was a decisive one for the fledgling Seventh-day Adventist Church.1 To put things in perspective, the General Conference had been organized only five years earlier, and it had been only a decade since Ellen White’s pivotal great controversy vision. Now, September 1-7, 1868, an estimated 200 to 300 individuals gathered to hold the first official, denomination-wide “camp meeting.” Held on the farm of Ephraim H. Root (1828-1906), who lived in Wright, Michigan, the idea of holding such gatherings was certainly not new or unique to these early church pioneers, but they did worry about whether it would really work to meet their needs and desire to share their faith.

Beginnings

Many who were alive in the 1860s would have been familiar with the rise of camp meetings, especially in the context of the Millerite revival from the 1840s. William Miller (1782-1849) noted how beginning in June 1842 at East Kingston, New Hampshire, such gatherings contributed to significant revivals.2 Adventists in 1849 reflected how such gatherings awakened “a general interest on the subject of the Lord’s speedy coming, and its kindred doctrines, our camp-meetings have been of incalculable importance, and in many instances, have accomplished much good.”3

Yet camp meetings can be traced even earlier. The open-air revivals held during the transatlantic Great Awakening were certainly a precursor. These revivals occurred because of immigration to colonial America, where such traditions and practices were adapted and appropriated in new and creative ways. The most important precursor for camp meetings was the Scottish Presbyterian practice of gathering semiannually with other believers to hear sermons calling for repentance and to celebrate the Lord’s Supper. These revivals in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries continued as the Second Great Awakening, particularly along the frontier. As revivalism became increasingly populist and democratic, this contributed to a greater emphasis upon personal emotional experience over intellect, and camp meetings became a key component to these ongoing revivals.

The specific innovation of camp meetings in America is generally attributed to a series of meetings in rural Kentucky in 1800. One attendee, Barton W. Stone (1772-1844), the following year organized one of the largest early camp meetings, held in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, in 1801. It was said that some came for religious reasons, but others came to gamble and cause trouble. Several Baptist and Methodist clergy joined in the preaching. As clergy made emotional appeals for repentance and spiritual renewal, some in the congregation laughed while others cried. The meeting lasted a week, and soon many others held similar gatherings that became ubiquitous across America. Charles Finney became legendary for popularizing the appeal for people to come forward to the anxious bench during such revivals.

The widespread popularity of camp meetings, including their use by Millerites during the 1840s, meant that early Sabbatarian Adventists began to consider whether this might be something they could utilize to share their religious convictions. Some expressed concern about religious excesses that at times characterized such gatherings. Some even opined that if Adventists held such meetings, it would be “a terrible mistake, a step backward.” Yet church leaders ultimately felt it would be worth the risk. Church leaders had begun to use large tents for evangelistic meetings. By 1867 a series of small, regional camp meetings in Iowa, Quebec, and Wisconsin effectively showcased how localized gatherings could unite church members and help to harness outreach efforts. James and Ellen White even attended the Wisconsin gathering with an estimated attendance of 1,200 people.

Trying it Wright

The initial success encouraged them to move forward with the first official and denomination-wide camp meeting. This was widely seen by church leaders, especially James and Ellen White, as a significant and historic event. The 1868 General Conference Session discussed how they could hold “a camp meeting for the whole field.”4 As they deliberated, Ephraim Root volunteered his farm as a location for the proposed camp meeting, modeled after the earlier Millerite camp meetings. The ensuing denomination-wide gathering served two purposes: a source of “spiritual good” and “the promulgation of our views among the people.”5 Such a “general gathering” would be near the town of Wright, a relatively “new field,” providing new opportunities to share the Adventist faith.6 Ultimately this gathering would be dubbed the first official and denomination-wide camp meeting. Review editor Uriah Smith specifically dubbed it as “the largest, most important, and by far the best meeting ever held by Seventh-day Adventists” up to that point.7

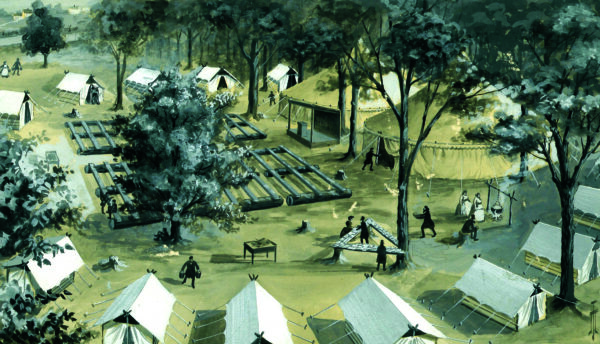

The maple grove or “sugar bush” Root farm was deemed an ideal location with both sufficient land and resources. The layout was described by J. O. Corliss as “very primitive.”8 Lodging consisted of bolts of factory cloth sewn together and spread over poles. The ends were fastened with nails to either upright posts or tree limbs cut just for the event. Eventually 22 makeshift tents were set up in a circle. Each tent represented a small church or group of families that could hold 12 to 20 people. As one participant remembered, James White woke up early, made a bonfire, and “prepared a kettle of hot porridge for all in the camp.” In “stentorian tones” he invited “all to come and be served.”9 Unfortunately, only one tent, the tent from Olcott, New York, the home church of J. N. Andrews, had a waterproofed covering canvas (or “duck canvas”), which after it rained, convinced other participants that for future camp meetings, waterproofed canvas was an essential requirement. James White had initially urged participants to obtain plain “cotton drilling” so that just in case the venture did not go well, participants could still use the material to make overalls or sack covers. The success of the camp meeting meant that the church needed to invest in proper waterproof sleeping tents.

Some of the tents were 60 feet in diameter. These large tents would become characteristic of both earlier and later camp meetings. The tents were erected as “a precautionary measure against the possibility of stormy weather.” The first tent was pitched to keep straw that was used for either bedding or feeding the horses dry.10 A second tent was reserved for use of campers and reserved as a meeting place in case it rained. Fortunately, the weather was pleasant overall, so the preaching was held in the open air instead. The pulpit was a simple, crude-covered structure made up of boards. The audience was seated on rough planks with risers taken from the nearby beech and maple trees. “The camp was lighted by wood fires,” wrote A. W. Spalding, “built on earth-filled boxes elevated on posts; and there were also log fires on the outskirts to warm the chilly.”11

The 1868 Wright camp meeting included a primitive Adventist bookstore—a bookstand that was placed at the camp entrance. Three 12-foot boards were placed in a triangle between the trees. The 12-inch boards gave just enough room to place an assortment of tracts, periodicals, and books from the Seventh-day Adventist Publishing Association. Behind stood an aspiring young minister, E. R. Palmer (1869-1931), who would become a lifelong worker in the Adventist publishing work, and John O. Corliss (1845-1923), who would serve as a preacher and missionary. Together they would sell more than $600 worth of books and tracts.12

Camp Meetings Proliferate

According to M. E. Olsen (1873-1952), the success of the Wright camp meeting led to the proliferation of camp meetings in the Seventh-day Adventist Church.13 Camp meetings were held later that year in Clyde, Illinois (September 23-30), and Pilot Grove, Iowa (October 2-7). The following year the General Conference recommended that state conferences organize all future camp meetings. Six such camp meetings would be held in 1869. As camp meetings became increasingly popular, it became common to pass along suggestions for how to have the best possible experience at such events. Such details included even pragmatic details such as directions about how to make your own camp meeting tent.14 James and Ellen White traveled to so many camp meetings that James found it expedient to publish the family’s bedding needs in the denominational periodical.15

During the 1870s there were five to 15 camp meetings held annually across North America. Camp meetings became a mechanism to bring together geographically separated believers to work, worship together, and hold evangelistic meetings. Often conferences and related church entities, such as the tract and missionary societies, in conjunction with these camp meetings, would hold their annual meetings and organize. Thus, camp meetings became an important feature facilitating organization and administration and providing a convenient venue to facilitate community outreach, raise funds, and garner support for denominational projects.

Often the topics of camp meeting sermons were geared toward attracting those who might be curious or who might have questions about spiritual matters. Ellen White’s preaching at camp meetings was frequently on temperance. She was also an effectual revivalist who could make altar calls. At one such camp meeting, held in 1874, Ellen White exhibited her “eloquence and persuasive powers” as “she implored sinners to flee from their sins.” According to Uriah Smith, during her appeal “probably 300 came forward for prayers, and it seemed as if the early days of Methodism had returned.”16 On another occasion, at a camp meeting in 1876 held in Groveland, Massachusetts, an estimated 4,000 people heard her speak about temperance.17 Throughout her lifetime it would be at camp meetings that Ellen White and other Adventist preachers drew some of their largest crowds. As Adventism spread across the continent and beyond, they continued to hold camp meetings. The first Adventist camp meeting on the West Coast occurred in Windsor, California, in October 1872. The first Seventh-day Adventist camp meeting held in Canada occurred in Magog, Quebec, August 21-26, 1879, and was organized by A. C. Bourdeau (1834-1916) and G. I. Butler (1834-1918). Altogether camp meetings remained a consistent way to solidify an Adventist identity as Adventism spread.

1 For an expanded and detailed treatment of “camp meetings” in Adventist history, see my article on this topic in the Encyclopedia of Seventh-day Adventists.

2 Sylvester Bliss and Apollos Hale, Memoirs of William Miller, Generally Known as a Lecturer on the Prophecies, and the Second Coming of Christ (Boston: Joshua V. Himes, 1853), pp. 164, 165.

3 Ibid., p. 306.

4 Arthur W. Spalding, Captains of the Host (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1949), p. 354.

5 See editor’s note, Review and Herald, Aug. 11, 1868, p. 128.

6 “General Campmeeting,” Review and Herald, Aug. 11, 1868, p. 128.

7 As quoted by William C. White, “Sketches and Memories of James and Ellen G. White: XLVIII—The First General Camp Meeting,” Review and Herald, Mar. 11, 1937, p. 4.

8 J. O. Corliss, as quoted in E. R. Palmer, “First Camp-Meeting Sales of Our Literature,” Review and Herald, Aug. 10, 1922, p. 24.

9 J. F. Piper, “West Michigan Camp-Meeting and Pioneers’ Day,” Review and Herald, Jan. 15, 1925, p. 18.

10 Virgil E. Robinson, John Nevins Andrews: Flame for the Lord (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1975), p. 71.

11 Spalding, p. 355.

12 Ibid.

13 Mahlon E. Olsen, “Adventists Become Health Champions,” Signs of the Times, Aug. 21, 1923, p. 10.

14 D. H. Lamson, “How to Make Tents,” Review and Herald, July 20, 1876, pp. 26, 27.

15 James White wrote: “We design to take a family tent with us to all our camp-meetings, and wish our brethren to provide for our company, board and bed-clothing for six. There should be at least one spring bed, and hair mattress, or their equivalent, for the worn and weary” (“Camp-Meetings,” Review and Herald, May 17, 1870, p. 176).

16 Uriah Smith, “Camp-Meeting Notings,” Review and Herald, Aug. 18, 1874, p. 68.

17 Ellen White stated that “it is estimated that twenty thousand people are assembled in this grove” (“Incidents at Groveland, Mass.,” Signs of the Times, Sept. 14, 1876; see also Ellen G. White manuscript 29, 1897). The “big day” of the Groveland camp meeting was August 27, 1876, at which she spoke about temperance (see Boston Evening Transcript, Aug. 24, 1876, p. 8). The Groveland camp meeting was held August 24-29, 1876 (see Boston Evening Transcript, Aug. 19, 1876, p. 8). The local newspaper estimated that the actual attendance was 4,000 at its peak (see Fall River Daily Evening News, Aug. 29, 1876, p. 2).