Those familiar with Adventist history will recall that our Seventh-day Adventist pioneers adopted a financial plan for giving known as “Systematic Benevolence,” as a precursor to our current practice of tithing.

Such Sabbatarian Adventist ministers as John N. Loughborough and John Nevins Andrews struggled to support themselves financially as they traveled preaching the gospel. As some ministers abandoned the work in discouragement, early church leaders quickly realized the gravity of the situation.

A REMEDIAL SYSTEM

To remedy ministerial burnout and facilitate gospel preaching, church leaders adopted a plan known as Systematic Benevolence in 1859. In retellings of our heritage, historians emphasize that the Adventist tithing system is rooted in the financial support for ministers who actively preach the gospel. This “standard” narrative is only half true, however. One of the twin principles of our tithing system has, unfortunately, been forgotten, at least in the retelling of our history.

According to religious historian James Hudnut-Beumler, many Christians in the United States began to promote Systematic Benevolence in the mid-nineteenth century. Systematic Benevolence was rooted in “two great purposes that God had placed before humanity: to take care of the poor and to spread the gospel.”¹ Adventist leaders were aware of these developments, and, after carefully studying the issue, they formally adopted Systematic Benevolence at the General Conference session held in Battle Creek, Michigan, in June 1859.

Like their non-Adventist contemporaries, Adventists emphasized that this new plan would systematize the mission of the church through focused attention on “the two great objects” of benevolence: financial and material support for poor individuals, seniors, widows, ministers, and missionaries

THE GOOD SAMARITAN INITIATIVE

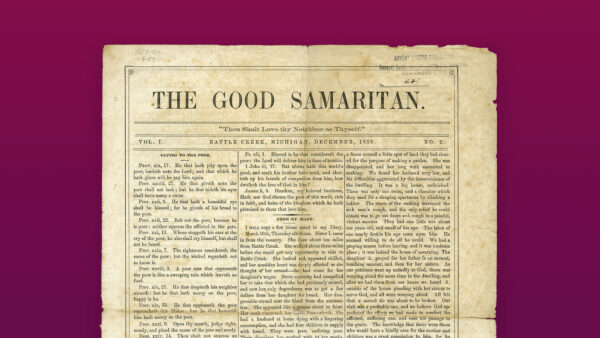

During the summer of 1859, Ellen and James White undertook a new publishing initiative to promote the twin principles of Systematic Benevolence. The new paper was titled The Good Samaritan. Unfortunately, only three issues are known to exist today. The first issue is among those missing, but it probably appeared in early August 1859, about a month after Adventists adopted Systematic Benevolence.

This quarterly paper promoted this new plan for financial giving and was “issued almost wholly with reference to the relief of the needy and distressed” under the motto on its masthead, “Thou Shalt Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself” (Matt. 22:39, KJV).²

The Good Samaritan was readily endorsed at a business meeting held in Battle Creek, Michigan, on August 7, 1859, and a committee was appointed “to receive donations of money or articles of apparel for the poor.” That committee was composed entirely of women, and included Harriet N. Smith, Ann J. Kellogg, and Huldah Godsmark.

Women, in fact, were the driving force behind Systematic Benevolence (which may be one reason it became known as “Sister Betsy” in Adventist circles). The first action of this committee was to appoint 48 agents—all women—in every state with an Adventist presence to collect money and clothing for ministers and laypeople in need.

Ellen White, a de facto co-editor of the paper, personally reported and published the actions of the committee in the second issue of The Good Samaritan, which appeared in December 1859.³

Over the next several months, Ellen and James White “pled the cause of the needy,” gave “force to this call to others,” and “set the example by giving largely themselves.” Their actions inspired others to champion the twin principles of Systematic Benevolence.

Abigail Palmer, of Jackson, Michigan, for example, bought a record book so that “each member of the family, or church” could record their weekly donations for “the widows, and fatherless, and the poor among Sabbathkeepers.”

When Lois J. Richmond first read The Good Samaritan, she wept because she believed that this was God’s plan for His church. Richmond was among the poor herself, but she was convicted that she could still contribute to the cause. She did so by organizing a group of adults and children who devoted about three hours per week to braid palm-leaf hats that could be sold to purchase “clothes for the poor and needy.” Within a month, Richmond’s braiding circle had raised “a little more than four dollars in money and clothes,” which she mailed to Ellen White to distribute among the underprivileged and oppressed.⁴

The Good Samaritan was apparently published with some regularity until early 1861. In March of that year, James White lamented that not enough written material had been submitted for publication, and that it was practical to publish the paper only occasionally. After the Civil War erupted in April, it became even more difficult to support three Adventist periodicals. The last known issue of The Good Samaritan appeared in June 1861.

A CONTINUED SYSTEM

Systematic Benevolence did not die with the paper, however. Adventist pioneers continued to emphasize and act on its twin principles as the church officially organized and continued to grow.

Today, many Adventists have forgotten that our tithing system developed out of a collective compassion for those who were poor, widows, fatherless, and seniors, as well as for the support of ministers and missionaries. These twin principles are what make our mission systematic—a mission of compassionate benevolence that serves both body and soul.

¹ James Hudnut-Beumler, In Pursuit of the Almighty’s Dollar: A History of Money and American Protestantism (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), pp. 6-31; R. F. Cottrell, “From Bro. Cottrell,” The Good Samaritan, December 1859, p. 8.

² J. N. Andrews, G. H. Bell, and U. Smith, Defense of Elder James White and Wife: Vindication of Their Moral and Christian Character (Battle Creek, Mich.: Steam Press, 1870), pp. 18, 19; Joseph Bates and U. Smith, “Business Meeting of B. C. Church,” Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Aug. 11, 1859, p. 96.

³ Bates and Smith; E. G. White, “[Business Meeting of the B. C. Church],” The Good Samaritan, December 1859, p. 6; James White, “Eastern Tour,” Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, Sept. 1, 1859, p. 116.

⁴ Abigail Palmer, “From Sister Palmer,” The Good Samaritan, February 1860, p. 12; Lois J. Richmond, “From Sister Richmond,” The Good Samaritan, December 1859, p. 8.