This article on William Miller, originally published in the Adventist Review on January 6, 1994, was written on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Great Disappointment (October 22, 1994). We share it again with you as we commemorate the day when William Miller first preached about the second coming of Christ on August 14, 1831.—Editors.

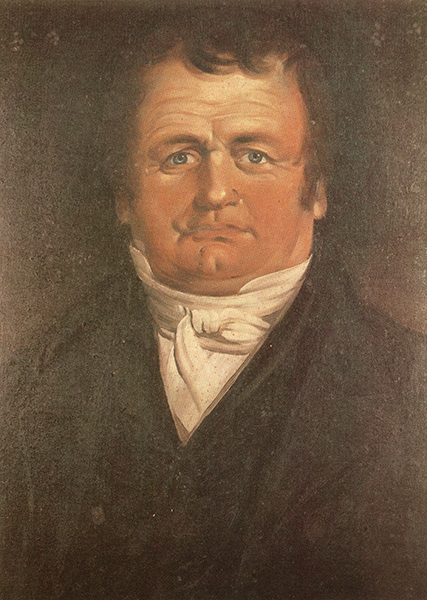

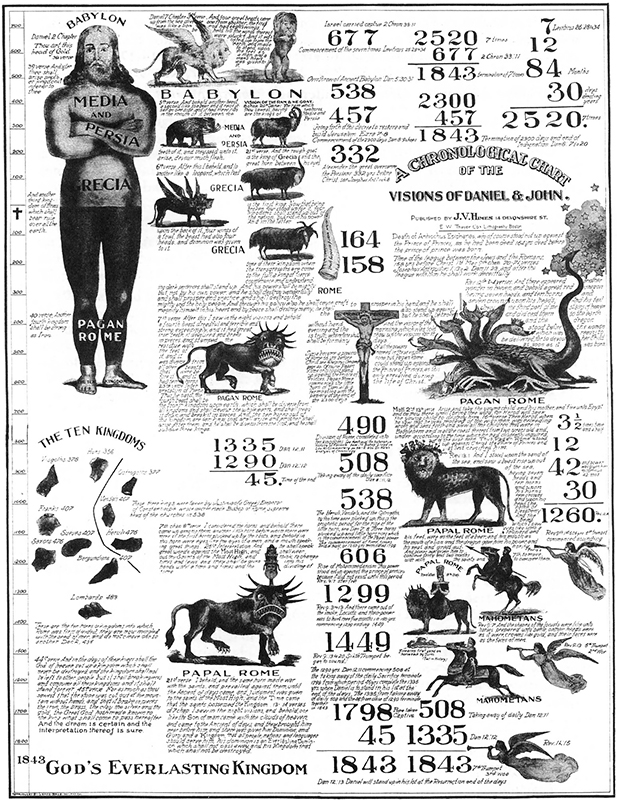

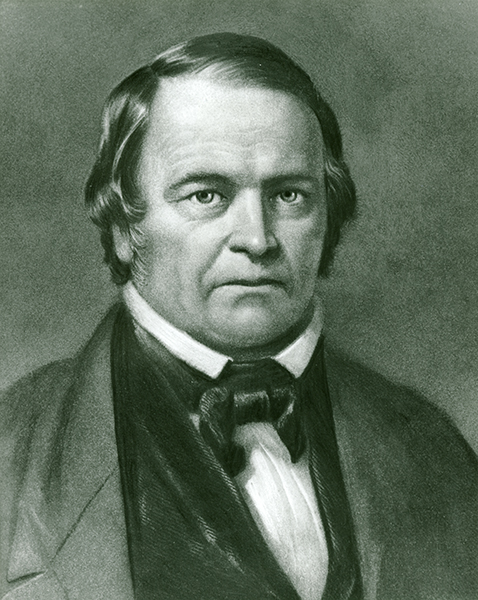

William Miller. For most of us his name is linked to October 22, 1844, the Millerite movement, and the time prophecies of Daniel and Revelation. But Miller’s revival movement, out of which the Seventh-day Adventist Church eventually emerged, was much more than just chronological dates and prophetic charts depicting fearful-looking apocalyptic beasts.

William Miller loved Jesus deeply. He loved people also, and feared that if not converted, they would be lost when Jesus returns. So he preached with an urgency that few of us have ever experienced and that ran against his own personal inclinations.

William Miller grew up in a Christian environment. Both a grandfather and an uncle were Baptist ministers.1 Although Miller’s father was indifferent to religion,2 his mother was a God-fearing woman who tried to raise her son to love the Lord.3

As early as between the ages of 7 and 10, Miller felt a concern for his own soul. He tells us: “I spent much time in trying to invent some plan, whereby I might please God. . . . Two ways suggested themselves to me, which I tried. One was to be very good, to do nothing wrong, tell no lies, and obey my parents. But I found my resolutions were weak, and soon broken. The other was sacrifice; by giving up the most cherished objects I possessed. But this also failed me.”4

Finding no apparent way out of his dilemma, Miller eventually began to read the writings of Voltaire, David Hume, Thomas Paine, Ethan Allen, and others. As a young man he turned to deism,5 a rationalistic way of viewing God that was then in vogue. For more than a decade Miller remained a skeptic.6 Among his deist friends he often mimicked the piety of his religious relatives, much to the amusement of his skeptical audience.7

Victory by the Outnumbered

When the War of 1812, between the United States and England, broke out, Miller, along with many of his fellow citizens, volunteered to defend his country.8 He fought in the Battle of Plattsburgh in upstate New York, where the Americans were outnumbered by the British forces nearly three to one.9 A cannonball fired from one of the invaders’ ships on Lake Champlain landed about two feet from Miller. Amid the exploding fragments from that shell, Miller was not even hurt.10 Why? he wondered. Could it be that there is a personal God who takes an active interest in the affairs of nations as well as of individuals?11 As he reflected on this and other experiences in his life, he began to question his skeptical views.

Discharged from the Army in 1815, Miller returned home, built his family a house (which still stands) in Low Hampton, New York,12 and settled down as a respected citizen of his community. Although wrestling in his mind with questions about his deistic views, he was not yet ready to give his heart to the Lord. But Miller did start attending the little Baptist church pastored by his uncle, which stood just down the road from his new home.13

On those Sundays when Miller’s uncle was called away to preach in a nearby church, one of the local deacons would read a selection from a book of sermons. Most of these men were not skilled readers, so their delivery left much to be desired in Miller’s eyes. In time, he became so disgusted with their faltering presentations that when he knew his uncle was going to be away on Sunday, he would remain at home.14

His mother asked him why he was absent from church. He told her about his negative reaction to how the sermons were read, adding that if he could do the reading, he would always be present. From then on, whenever Miller’s uncle was away the deacons chose the sermon to be read, but Miller presented it.15

Questions Still Arose

Although he was still a deist, questions and doubts kept crowding into his mind. One deistic belief that haunted him was the idea that when one dies, there is nothing beyond the grave. He later wrote: “Annihilation was a cold and chilling thought. . . . The heavens were as brass over my head, and the earth as iron under my feet. Eternity!—what was it? And death—why was it?”16

Miller remained in this unsettled state of mind for several months. One Sunday he was asked to read a sermon written by Alexander Proudfit on the “Importance of Parental Duties.” As he read he became so overcome with emotion that he had to sit down. His deistic principles seemed to present an almost insurmountable difficulty.17 But a short time later, “suddenly the character of a Saviour was vividly impressed upon my mind. It seemed that there might be a Being so good and compassionate as to Himself atone for our transgressions, and thereby save us from suffering the penalty of sin. I immediately felt how lovely such a Being must be; and imagined that I could cast myself into the arms of, and trust in the mercy of, such an One”18

Miller then wondered how to prove the existence of this Being. He said, “I felt that to believe in such a Saviour without evidence would be visionary in the extreme.”19 Now, for the first time in his life, he wanted to know what kind of God is revealed in Scripture.

As he began to study, he discovered “that the Bible did bring to view just such a Saviour as I needed; and I was perplexed to find how an uninspired book should develop principles so perfectly adapted to the wants of a fallen world. I was constrained to admit that the Scriptures must be a revelation from God. They became my delight; and in Jesus I found a friend. The Saviour became to me the chiefest among 10,000; and the Scriptures, which before were dark and contradictory, now became the lamp to my feet and light to my path. My mind became settled and satisfied. I found the Lord God to be a Rock in the midst of the ocean of life.

“The Bible now became my chief study, and I can truly say, I searched it with great delight. I found the half was never told me. I wondered why I had not seen its beauty and glory before, and marvelled that I could have ever rejected it. I found everything revealed that my heart could desire, and a remedy for every disease of the soul. I lost all taste for other reading, and applied my heart to get wisdom from God.”20

A Changed Man

Miller immediately began to conduct family worship, publicly joined the Baptist Church, made his house available for prayer meetings, and began to assist in the work of the church.21 During this period, 1816-1818, when Miller was devoting so much time to intense Bible study, he discovered the 2,300-day prophecy of Daniel 8:14, with which his name would be forever linked.

Miller sincerely believed that Christ would come back to earth around 1843 or 1844. He could scarcely contain his excitement at the thought that his newfound Friend, Jesus, would return in about 25 years! He said, “I need not speak of the joy that filled my heart in view of the delightful prospect, nor of the ardent longings of my soul for a participation in the joys of the redeemed.”22

He derived much pleasure from the study of the Bible, and it was almost his constant companion. He set aside a portion of each day for personal Bible study. “He loved to meditate on its teachings and to talk about its promises.”23And his love for Jesus continued to deepen.

To a minister friend, Miller wrote in 1832: “I would . . . advise you to lead your hearers by slow and sure steps to Jesus Christ. I say slow, because I expect all are not strong enough to run yet; and sure, because the Bible is a sure word—and where your hearers are not well indoctrinated, you must preach Bible; you must prove all things by Bible; you must talk Bible; you must exhort Bible; you must pray Bible, and love Bible; and do all in your power to make others love Bible, too.”24

In another letter to this same friend he exclaimed: “Give me Jesus, and a knowledge of His Word, faith in His name, hope in His grace, interest in His love, and let me be clothed in His righteousness, and the world may enjoy all the high-sounding titles, the riches it can boast, the vanities it is heir to, and all the pleasures of sin; and they will be no more than a drop in the ocean. Yes, let me have Jesus Christ, and then vanish all earthly toys. What glory has God revealed in the face of Jesus Christ! In Him all power centers. In Him all power dwells. He is the evidence of all truth, the fountain of all mercy, the giver of all grace, the object of all adoration, and the source of all light; and I hope to enjoy Him to all eternity.”25

Many people have written about the Millerite movement. But to properly understand it, one must realize that Miller was someone who had fallen in love with Jesus. Nothing was more precious to him than the thought of Christ’s soon return. But there were millions of others who would be lost because they had not yet accepted Jesus as their personal Saviour. The possibility of anyone missing out on eternity was more than Miller could bear. He said, “When I was about my business, it was continually ringing in my ears, ‘Go and tell the world of their danger.’”26 This thought drove him to go preach—year after year—usually giving two two-hour lectures on the prophecies per day. Between 1832 and 1844, Miller estimated that he preached 4,500 sermons to at least half a million people.27

Although Miller’s mistaken belief that Jesus would return about 1843 or 1844 gave an urgency to his preaching, time was not his entire message. He longed for people to accept Jesus as their personal Saviour and to be ready to meet Him when He returned. Miller closed one sermon with this appeal: “What is the ground of your hope, my dear friend? If you love Him not now, how can you expect to love Him here after? If you can sacrifice nothing in this life, how can you expect to receive the benefits of that sacrifice which cost the Son of God a life of poverty, deprivation, and distress? which cost Him groans and tears and blood in the garden? which cost Him mockings, tauntings, and scourging in Pilate’s judgment hall? which cost Him sweat, and blood, and death on the cross? Think, my brethren, oh! think of the passion of Christ; and if that will not move you to a more active and diligent life in His cause, then you may safely conclude you have no lot nor part in that glorious hope which He hath laid up for all those who love His appearing.”28

That any person taking the name Christian could be upset at the prospect of Christ’s return was something Miller could not comprehend. In his Apology and Defence, published in 1845, Miller revealed why he hadn’t started sharing his views on Christ’s second coming even earlier than he did: “I supposed that it [the Second Advent] would call forth the opposition of the ungodly; but it never came into my mind that any Christian would oppose it. I supposed that all such would be so rejoiced in view of the glorious prospect, that it would only be necessary to present it, for them to receive it. My great fear was, that in their joy at the hope of a glorious inheritance so soon to be revealed, they would receive the doctrine without sufficiently examining the Scriptures in demonstration of its truth. I therefore feared to present it, lest by some possibility I should be in error, and be the means of misleading any.”29

From the time of Miller’s conversion, being with Jesus and doing all in his power to help others to be ready for His return impelled his life. After the first disappointment in the spring of 1844, when Jesus did not return as expected, he wrote:

“How tedious and lonesome the hours,

While Jesus, my Saviour, delays!

I have sought Him in solitudes bowers,

And looked for Him all the long days.

“Yet He lingers—I pray tell me why

His chariot no sooner returns?

To see Him in clouds of the sky,

My soul with intensity burns.

“I long to be with Him at home,

My heart swallowed up in His love,

On the fields of New Eden to roam,

And to dwell with my Saviour above.”30

Although Miller died in 1849 without seeing his fondest hopes realized, Ellen White was shown God’s eventual reward for this dedicated pioneer: “Angels watch the precious dust of this servant of God, and he will come forth at the sound of the last trump.”31 Finally, on the great resurrection day, Miller will get his heart’s desire: to be with his Friend, Jesus.

1 Sylvester Bliss, Memoirs of William Miller (Boston: Joshua V. Himes, 1853), p. 28.

2 See Bliss, p. 4.

3 See Bliss, pp. 29, 30.

4 Quoted in Joshua V. Himes, Views of the Prophecies and Prophetic Chronology, Selected From Manuscripts of William Miller; With a Memoir of His Life (Boston: Moses A. Dow, 1841), p. 9.

5 William Miller, Apology and Defence (Boston: J. V. Himes, 1845), pp. 2, 3.

6 Bliss, p. 25. 7 Ibid., p. 29.

8 Ibid., pp. 31, 32.

9Ibid., p. 52.

10 Ibid., p. 47.

11 See Miller, p. 4.

12 Bliss, pp. 59, 63. 13 Ibid., p. 64.

14Ibid., pp. 64, 65.

15 Ibid.

16 Quoted in Bliss, p. 65.

17 See C. Mervyn Maxwell, Tell It to the World, (Mountain View, Calif.: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1976), p. 12, and note 4 on p. 271; also, Bliss, p. 66.

18 Bliss, p. 66. 19 Ibid., p. 67. 20 Ibid.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid., p. 76.

23Ibid., p. 85.

24 Ibid., pp. 100, 101.

25 Ibid., p. III.

26 Miller, p. 15.

27 The Midnight Cry! Feb. 15, 1844, p. 236.

28 Himes, p. 130.

29 Miller, p. 13.

30 Bliss, p. 262.

31 Ellen G. White, Early Writings (Washington, D.C.: Review and Herald Pub. Assn., 1945), p. 258.