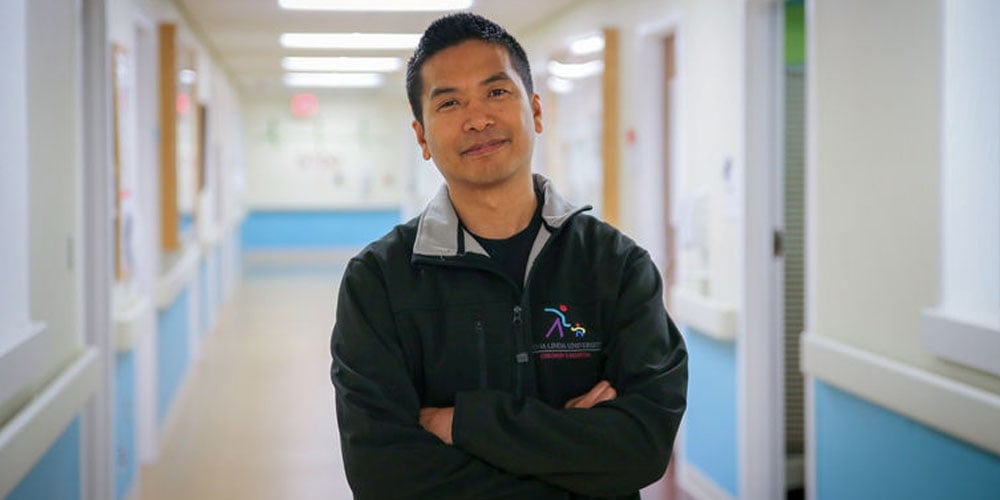

Merrick Lopez, a pediatric intensivist physician at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital, says he remembers when, in early 2020, health officials and news sites started buzzing about an unknown virus that hadn’t yet reached the United States.

A U.S. State Department-chartered plane carrying upwards of 240 U.S. citizens from the Wuhan region of China, the suspected origin point of the virus, was set to arrive in nearby Riverside, California, about that time.

“At first, we didn’t know what to worry about or how much to worry,” Lopez says. “When we heard the plane was going to land in Riverside, a colleague told us, ‘Just get ready. Everybody get ready.’ And we thought, ‘Ready for what?’ ”

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

Once cases started to spread in the U.S., the myriad unknowns surrounding how to prepare for the virus, how to treat the virus, and how health care was going to continue with the virus caused immense stress for Lopez’s teams in Children’s Hospital, as well as the adult teams in Loma Linda University Medical Center.

Lopez has spent 23 years in the health-care field, several years as a nurse, but most of his career as a physician. Despite his wealth of knowledge, COVID-19 was for him, like many other doctors, a big unknown. He was named medical director of the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) a few months before the onset of the pandemic, and his experience in this role has been strongly shaped by the virus and its youngest victims.

Pandemic Simulations

Lopez and his department were among the first in the hospital to run COVID-19 simulations in preparation for what they suspected would be an onslaught of very sick, highly contagious patients. These simulations included practicing donning the required personal protective equipment in the event of a COVID-19-positive patient.

Searching through any available literature from Wuhan and working with hospitals throughout the country, Lopez and his team created checklists, developed scenarios, and ran drills through the simulation department as quickly as they could. They then spread the word to other departments that simulations were potentially a valuable step to take before patients arrived.

But just as they expected to see a surge of pediatric patients, their units became virtually empty. “Everything was heightened, we were ready, but with the stay-at-home orders and social distancing, we didn’t get patients,” Lopez says.

In adult hospitals like the Medical Center, however, cases began to surge, leaving Lopez's adult colleagues overrun. Although Children’s Hospital opened up to admit adults up to age 30, Lopez says they felt helpless to assist. “We could not help them because most of their patients were above 60 years of age,” he says. “Some of the nurses on our unit described it as a kind of survivor's guilt because we saw how difficult it was for them.”

Children’s Hospital’s First COVID-19-positive Patient

Children’s Hospital had its first COVID-19-positive admission in late April 2020. The patient’s diagnosis was grim, with multiple co-morbidities and the need for intubation. Huddled outside the patient’s room for a few moments, Lopez and his team pulled together their thoughts, fears, and training. “We were worried,” he says. “We wanted to be protected but wanted to do the right thing for this patient and knew something had to be done. There was fear, but an overwhelming determination to do what needed to get done.” The group offered up a prayer before jumping into action.

Close by was the patient’s crying, terrified mother, who also had COVID-19 symptoms. Lopez struggled to find words for her. Should he tell her to prepare for a bad outcome or that there was still hope? “For this one time, we just didn’t know, and nobody around the country really knew how these types of patients were going to fair.”

That patient, despite many odds, did recover after an extended ICU stay. Numerous staff lined the halls and clapped for the patient as they left the unit. “We were happy — so happy for them,” he says.

The Surges

Lopez and his team would treat many more patients from this point on. They experienced the first PICU surge in June through August of 2020. Cases of multi-inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) in children appeared and began to rise.

The first surge paled in comparison to the second surge from December 2020 through February 2021. “It was the super peak — everything was full,” he says. Lopez’s teams started taking adults ages 18-30 to help relieve some of the burdens on their colleagues caring for adult patients. “We felt so bad for them,” he says. “But alongside that survivor’s guilt, I had never been so grateful to be a pediatrician.”

Lopez, who also works for the hospital system in Riverside, saw many pediatric physicians and neonatologists voluntarily go to the emergency departments to work and cover shifts — physicians who had only worked with kids and babies were now caring for adults ages 60-90.

He was inspired by his colleagues who jumped to the front lines, including the many nurses and respiratory therapists who were caring for COVID-positive patients for endless shifts. He says while there was fear in some, others, despite their ages, maintained an attitude of courage and focused on caring for the patients in need. “Several physicians over the age of 65, who weren’t required to care for the COVID-19-positive patients for their own safety, did so anyway, saying, ‘If it’s my time, my time has come,’ ” he says.

Lopez Contracts COVID-19

Lopez continued to worry about passing COVID-19 on to his family, especially in the early days of the pandemic. But as the medical director, he knew he needed to support his team and take responsibility even if he was afraid. Lopez took every possible precaution to keep his family safe, and despite many close calls, neither he nor his family members contracted COVID-19 during the first two surges.

Unfortunately, sometime during August 2021, Lopez and half his family were met with the Delta variant. His entire family had been previously vaccinated, except for his two youngest kids, who were not yet eligible for the vaccine. With his mom over 70 and his dad recently having open heart surgery and a heart attack, both his parents could have easily become devastatingly sick.

While they were waiting for their test results, Lopez says he kept praying for peace and guidance in moving forward. The tests came back positive for Lopez, two of his kids, his mom, and later on, his wife. “I was devastated — knowing how hard we tried to protect my parents throughout the pandemic, only now to put them at risk,” he says. However, no one in the Lopez family became very ill, including his vaccinated parents, all recovering quickly at home with only minor symptoms.

Shifting Perspectives

Lopez says he initially felt angry with himself about contracting COVID-19. He’d made it through so much with his patients without getting sick. But now, he understands it as a way to better empathize and be a better physician overall.

“I’m more sympathetic and understanding to what they’re going through now, because even though I took every precaution in my family, we still got sick,” he says. “I can walk into a COVID-19-positive room, hold their hands with less fear, and say to them, ‘Hey, I had COVID too — we'll get through this.’ ”

Lopez expresses overwhelming admiration and respect for his colleagues working with adult patients. “They’ve had to watch so many patients die,” he says. “Some of them are extremely burnt out.”

And what does the future look like in health care to Lopez? He says while he doesn’t know for sure, he is hopeful because of how he’s watched his team pull together through the pandemic. “Surprisingly, it’s reassuring — reassuring to know we can go through something like this and bond together to get through,” he says. “I hope that the worst is over, but even if there’s another surge, we know the next steps to take.”

The original version of this story was posted on the Loma Linda University Health news site.