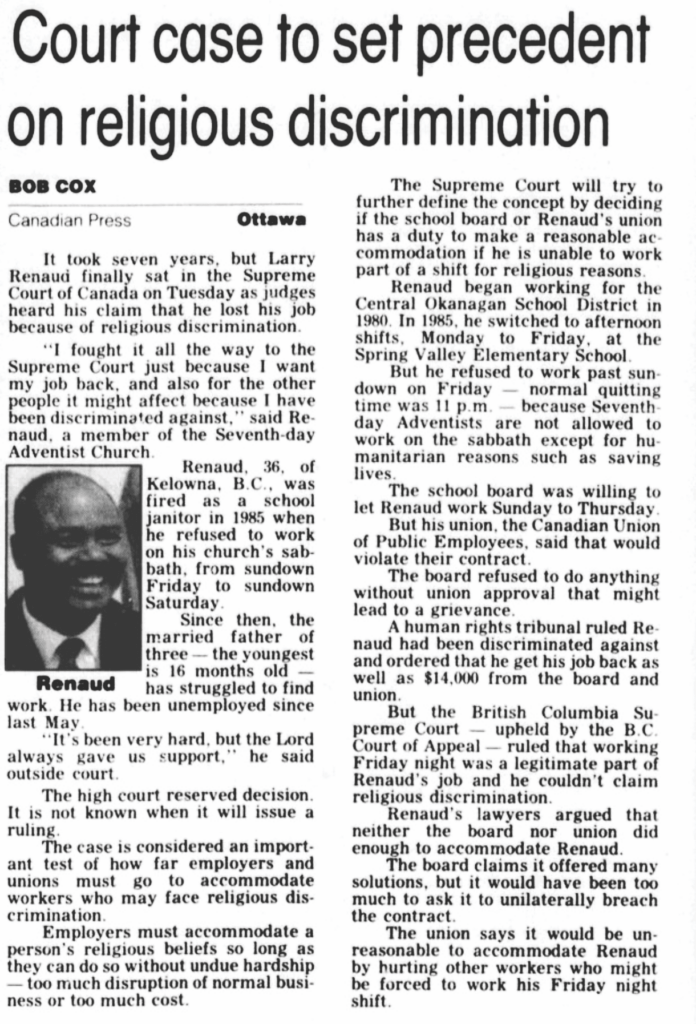

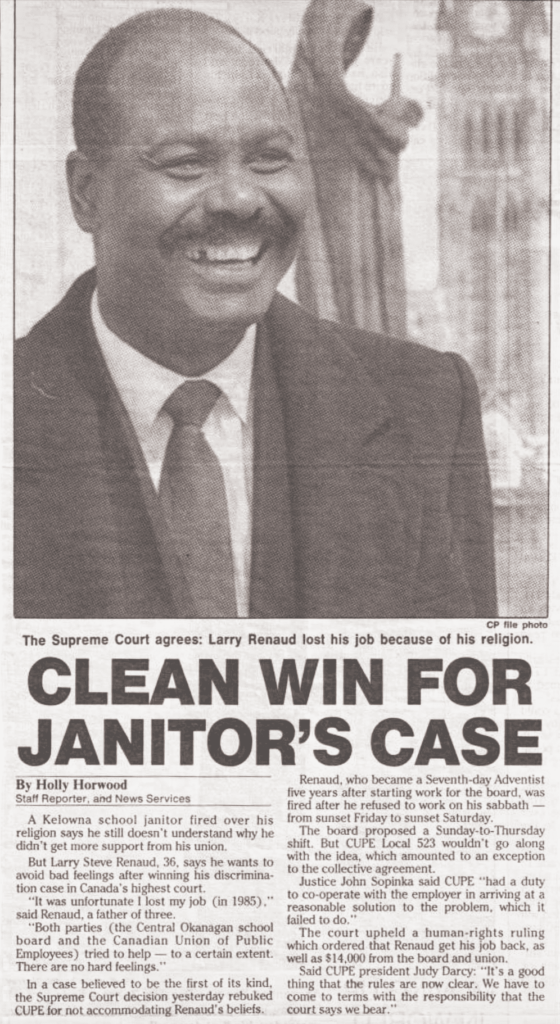

Thirty years ago, in 1992, the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) ruled in favor of Larry Steve Renaud’s conscientious stand not to work on the Saturday Sabbath.* The court held that both the employer and labor union had to negotiate an accommodation while acknowledging the employee’s duty of reasonableness in seeking an accommodation. It was a ground-breaking case.

“I learned through this experience that it isn’t easy to stand up for your beliefs,” Renaud recalls, “but you need to be able to follow your conscience, because that is ultimately where you find peace. Knowing you are obeying God’s law, though maybe difficult, is comforting.”

Originally from Haiti, Renaud immigrated to Canada in 1972. In 1980, School District #23 in Kelowna, British Columbia, hired him as a custodian. Convicted about the seventh-day Sabbath in 1985, he found that a crisis of conscience arose. His beliefs meant he could no longer work Friday evenings after sunset.

Approaching his employer for Sabbaths off, he was told to use up his holiday time. This temporary solution worked for only a few months. The employer suggested contacting the union, as any accommodation required changing the collective agreement. The union was displeased he had spoken to the school district first. The union also reasoned changing the agreement for Renaud would open the door to similar requests from others.

“I had a difficult time with this,” Renaud remembers, "because [the union] made allowances for a co-worker to play music with his band in a bar on multiple Friday nights, and that was OK." So why not allow him to have Sabbath off? He was willing to work Saturday evenings and Sundays to ensure the school was clean for Monday classes. Still, his suggestion was rejected partly because the collective agreement required overtime pay for evening and Sunday shifts. Renaud was willing to work for regular pay, but this accommodation, along with other accommodations, was rejected by the union that did not want to change its collective agreement. The union threatened a grievance if the school district accommodated him.

With a young family to care for, it wasn’t easy for Renaud to lose his job. Friends chastised him over his choice. His first duty, they exhorted, was to his family, and he must remain at work until God led him elsewhere. Renaud chose to lose his job and honor God.

A Legal Challenge Is Born

The intake person at the unemployment office informed him that his dismissal from the school district was wrong. As Renaud explains, “One thing led to another as this situation took on a life of its own, as I didn’t plan for this to happen. I was directed to file a complaint with the human rights authorities, and that is where the legal challenge began.”

During the various stages of the legal proceedings, Renaud continued to trust God. He admits, “The experience was a bit like a roller coaster ride — ups when the ruling was in my favor and downs when a higher court ruled against me. The case became a part of everyday life, but it didn’t consume me because I trusted God and knew He was in control.

“I was able to enjoy life,” Renaud adds. “My business ventures were pleasurable for me because my little boy accompanied me with my yard maintenance and was often with me selling ice cream. I had the support of my whole family delivering flyers.” No doubt, the ice cream business was a big hit with his family!

Renaud retained a legal aid lawyer. The British Columbia Council of Human Rights ruled in his favor, but on appeal, the British Columbia Supreme Court (BCSC) ruled against him. At that point, the legal aid lawyer said he did not have the expertise or financial support to continue the case.

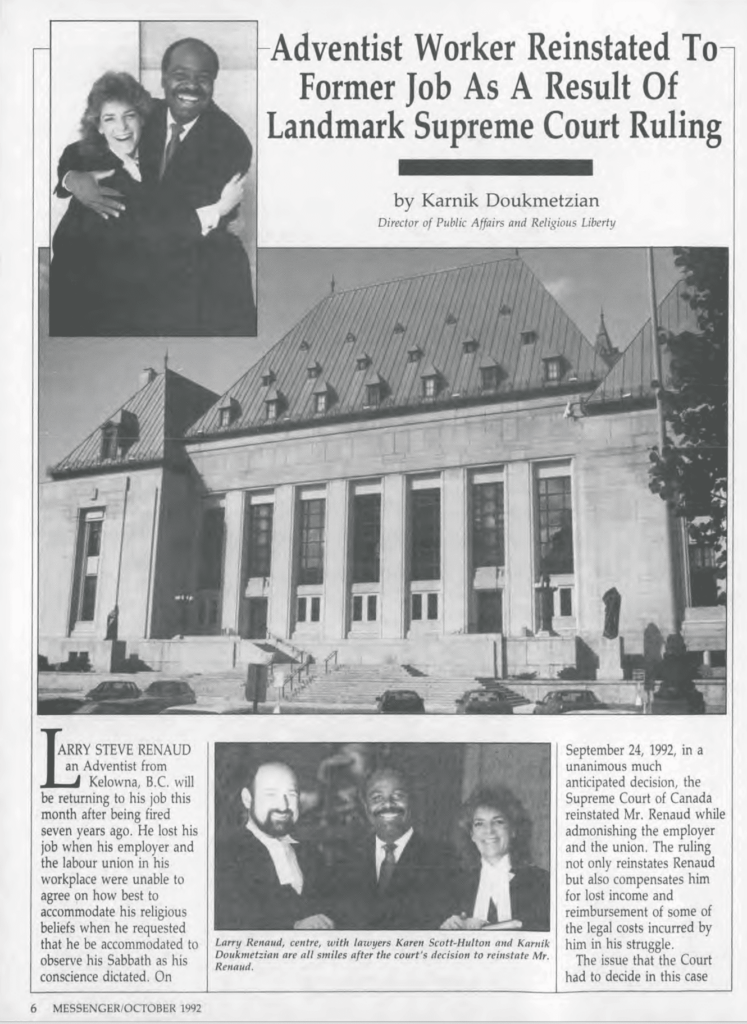

That was when lawyer Karen Scott was retained. Renaud had been impressed when he heard Scott speak at Camp Hope about a religious liberty case she had worked on, so he contacted her for assistance. She was in solo private practice and only six months beyond being called to the bar. In other words, she was at the very beginning of her legal career.

Scott immediately recognized that the case would eventually go to the country’s highest court after the British Columbia Court of Appeal (BCCA) hearing. She explains, “The SCC had already ruled employers have a duty to accommodate employees’ needs, but what is an employer’s duty to accommodate when there’s a collective agreement in place? This was the first time in Canadian legal history this question was before the courts.”

She suggested Renaud and his wife, Siegrid, get a more experienced lawyer. Renaud recalls, “When I first asked her to take on my case, she felt that she didn’t have the needed experience to properly represent me. My answer to her was that I would rather have a lawyer with faith and trust in God and little experience than a lawyer with much experience but no faith and trust in God.” He remembers she “worked hard and prayed harder, and she was a solid support all the way through. She shared in my disappointments, hopes, and ultimate victory as a friend and not just a lawyer representing my case.”

Karnik Doukmetzian, then Public Affairs and Religious Liberty director for the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Canada (SDACC), agrees: “Karen singlehandedly carried the load of this case on Steve’s behalf. [It was] a valiant battle to correct a wrong.” Doukmetzian’s office provided Scott with the financial resources she needed to get the job done.

The seven-year legal journey had its difficult moments. Renaud struggled with misrepresentations made in court by the employer and union, and his “eyes were opened” when reporters misquoted him. “The first time that happened was such a shock!” he recalls. Then there were natural letdowns when he lost, followed by jubilation when he won. Looking back, he saw it as a net gain for God’s kingdom, because he was able to witness to the importance of keeping the Sabbath.

When strangers on the street would sometimes recognize him from newspaper articles and call him “Larry,” as the media referred to him, his family and friends teased him endlessly because they all knew him as Steve, which is his middle name and the one he goes by.

At every level, Renaud was present to hear the arguments live. From the judges’ questions, he gained clues as to what the outcome would be. At the BCSC, he noted the derision toward the decision of the British Columbia Council of Human Rights. Again, at the BCCA, the three judges were very sympathetic toward the employer and union. At the Supreme Court of Canada, he observed a different demeanor. The judges asked direct and intense questions of the lawyers for the school district and union. “This time, they were on the defensive,” Renaud says, “and it was very obvious that the judges were leaning in our favor. That was such a wonderful feeling.”

While Renaud trusted God, Scott trusted Him also. She was acutely aware of the magnitude of the case, recalling, “I had not just the fate of Steve’s future in my hands but the fate of every Sabbath keeper in the nation. That’s when I prayed even more for God’s guidance and direction as well as asking that He prepare the hearts of the judges to decide in Steve’s favor.”

The night before appearing before the Supreme Court of Canada, Scott prayed for wisdom. “I didn’t just want to read my submitted written argument,” she recalls, “but nothing seemed to work. So once again, I cried out to God about how important this case was and how I was unable to do anything myself. As I had previously advised clients seeking exemption from union membership, I now claimed His promise in Luke 21:14-15 for the words needed. I am still amazed at how God answered that prayer. Suddenly the words just flowed onto my paper. After weeks of struggle, I finally had the oral argument to present to the court.”

Because of the importance of the case, three entities — the Ontario Human Rights Commission, Disabled People for Employment Equality, and Persons United for Self-Help in Ontario, as well as the Seventh-day Adventist Church in Canada — were granted permission by the SCC to argue before the court.

Doukmetzian, arguing on behalf of the SDACC, remembers the day of the hearing: “We were all very nervous about being before the highest court in the land, not only to support Steve but the church and our beliefs. It was a privilege for us, as Adventist lawyers, to be before the court.” The victory now stands as the foundation not only for employment accommodation to all religions but also for the rights of accommodation for disabled persons and others.

The Renaud case continues aiding not just those in Canada needing Sabbath accommodation but those needing accommodation for other needs such as disability. Unions nationwide now support the case. Some scholars believe the Renaud decision is one reason Canada leads the world in providing positive work environments. God continues blessing many, 30 years later, as a result of Renaud’s commitment to honor and obey Him.

The original version of this story was posted in the January 2022 issue of Canadian Adventist Messenger.

_______________________

*Central Okanagan School District No. 23 v. Renaud, 1992 CanLII 81 (SCC), [1992] 2 SCR 970, https://canlii.ca/t/1fs7w.