When we think of the Sabbath, we typically think of a weekly day of worship, or a work sabbatical. But when our ancestors “remembered the Sabbath day, to keep it holy,” they sometimes took their lives in their hands.

The English Parliament of 1584-1585, on behalf of the growing Puritan movement, passed a bill requiring strict observance of the Sabbath (in their case, Sunday, the first day of the week). The bill forbade markets and fairs, and recreation such as bear baiting, hunting, hawking, and rowing barges during church service time. It was argued for two weeks before passing and being sent to Queen Elizabeth I.

The queen vetoed the bill, in line with her policy of religious tolerance (though Catholics remained on the naughty list):

“And yet at last when it was agreed on by both the said Houses, it was dashed by Her Majesty at the last day of this Parliament, . . . that she would suffer nothing to be altered in matter of Religion or Ecclesiastical Government.

The Puritans who yearned for this strict Sabbath observance were not a separate denomination, but a movement within the Church of England that sought to purge the church of its Roman Catholic roots. Puritans were vocal and refused to compromise their beliefs.

Nicholas Bownde’s scholarly book True Doctrine of the Sabbath, published in 1595, urged Christians to sanctify the Sabbath as a day of meditation and spiritual exercises (morning and afternoon preaching services). These Sabbaths were meant to follow the Old Testament scriptures about keeping the Sabbath holy by not working or “doing your own pleasure,” as a moral imperative. Sabbaths were to be solemn and sober, with no secular speech or acts. Queen Elizabeth and the archbishop of Canterbury decreed that copies of Bownde’s book be collected and burned in 1600 and 1601.

In 1601 the House of Commons passed a bill that restricted markets and fairs on Sundays, but allowed other secular activities. The House of Lords killed it.

When Queen Elizabeth died two years later, and King James I came to the throne, his authority was threatened by Puritans and other Calvinist dissenters (such as the group that became the Pilgrims), whose influence was growing ever stronger and whose sermons and pronouncements conflicted with his authority.

One of James’s first acts was to commission a new version of the Bible that stressed the sovereignty of God and the hierarchy of worldly kings and princes. The Authorized (or King James) Version was published in 1611. Puritans hated it, preferring their 1560 Geneva Bible, with its commentary, illustrations, hatred of the Roman Catholic Church (In the Geneva Bible, Revelation 11:7 specifically named the beast as the pope.), and elevation of common humanity.

Their continued agitation all over England earned them the name “dissenters.”

In 1617-1618 the king went on a progress (on tour) through the country, holding courts and meeting his subjects. One of the complaints he heard was that the usual workweek being Monday through Saturday from dawn to dusk, people needed at least a half day for recreation, markets, fun fairs, visiting family, and the like. The Puritans were preventing that by holding two long services on Sunday.

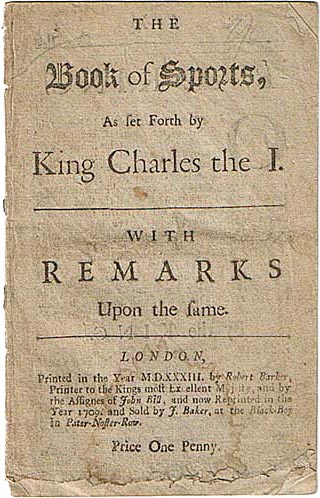

As answer to the problem of overwork and an unbalanced life—and that should he need soldiers for war, they’d be puny and weak—King James wrote The Book of Sports. The 1,500-word booklet directed his subjects to go to church on Sunday morning and religious holidays as required, but to spend the afternoon enjoying life.

He commanded that “no lawful recreation shall be barred to our good people,” and listed appropriate activities for those days: “such as dancing, either men or women; archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation, nor from having of May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances; and the setting up of May-poles and other sports.” Women were granted permission “to carry rushes to the church for the decorating of it, according to their old custom.”

The Book of Sports not only allowed certain recreational activities—it also forbade “all unlawful games” such as bear and bull baitings, and bowling.

But what might have been the reason for prohibiting bowling? The answer turns out to be that “a Bowling-Green, or Bowling-Ally, is a place where three things are thrown away besides the Bowls, viz., Time, Money, and Curses, at the last ten for one.”*

The king further commanded that The Book of Sports be read in every church, and held the bishops, ministers, and churchwardens accountable that it should be done “by the book.”

After King James’s death in 1625, the book was reissued several times by his son Charles I. In an attempt to control the Puritan (and other nonconformist) uprising, King Charles decreed that The Book of Sports be read again in all churches. Churches were also required to conform to the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, which was also hated by the Puritans. Puritan ministers who did not conform were “silenced” by being removed from the pulpit and denied a preaching license. Some were imprisoned, a punishment that could be a death sentence because of disease and exposure to extremes of cold and hunger.

Further, The Book of Sports included this command: “The Bishop, and all other inferior churchmen and churchwardens, shall for their parts be careful and diligent, both to instruct the ignorant, and convince and reform them that are misled in religion, presenting them that will not conform themselves, but obstinately stand out, to our Judges and Justices: whom we likewise command to put the law in due execution against them.”

However, there was a loophole in The Book of Sports that many Puritan ministers latched onto: “Constraining them to conform themselves or to leave the country.”

Leaving, however, presented its own complications: the king didn’t want them to leave the country because he would lose all their tax revenue; if they did sneak out, they couldn’t go to Catholic France or Spain; again, such Protestant nations as Lutheran Germany and Austria were at war with France, Italy, and Spain. The Netherlands was a destination of hope. Some, like the Pilgrims of England, went there for 10 years before they sailed to Massachusetts. Among their leaders was John Robinson, one of my ancestors 12 generations back. His chapter on the first-day Sabbath in his book A Just and Necessary Apology was published in 1625, the year he died.

For most Puritans there was no place to go but to America, still under English rule but 3,000 miles away by dangerous ocean journey from the king and the archbishops of the Church of England.

Some ministers escaped the long arm of the law by hiding with the help of sympathizers such as the earl of Lincoln, until the earl was imprisoned. The senior pastor of St. Botolph’s Church, John Cotton, was one of many ministers who had to hide before escaping to New England. Ten percent of the citizens of Boston, Lincolnshire, emigrated to Massachusetts Bay Colony with him or shortly after Cotton went there. Cotton had been asked to come to Massachusetts several times, but kept declining invitations until fear of being imprisoned forced him out of England.

Entire towns in many English counties emptied and sailed to the new Boston (the New Jerusalem, they hoped) between 1630 and 1640. About 35,000 people are estimated to have settled in New England during that decade. When the English Civil War began, with Puritans in ascendancy, thousands of the emigrants moved back to England. In May 1643 angry Puritans burned The Book of Sports in London.

Christians who experienced the threat of persecution and death were deeply convicted of the truth of their beliefs. They followed biblical laws to the letter to prove to God that they were worthy of salvation. The fourth commandment, to keep the Sabbath holy, was one of the factors that caused their persecution in the first place. Obedience to God was worth moving across the world, or dying for.

Both on their ships and in New England they followed stringent regulations about Sabbathkeeping. English Church holidays such as Christmas and Easter were prohibited, and people were expected to work as usual. Church services with required attendance were held Sunday mornings and afternoons. During the Sabbath there was no alcohol consumption, no unseemly walking, no court or corporal punishment, no work that could be done another day, no swimming, no buying or selling, no games or dances, no unnecessary travel, no hunting or fishing. Music or literature was sacred, never secular. Sabbath began at sundown on Saturday evening and ended the night before Monday.

Adventists in the 1840s, many of whom lived in Puritan (later Congregational) New England, learned about the seventh-day Sabbath from Seventh-Day Baptists.

People in Sabbatarian denominations (Seventh-day Adventist, Seventh-Day Baptist, messianic synagogues, Church of God, etc.) came to see the Sabbath as a gift, a special grace dispensed by God. Others see seventeenth-century culture and marvel at the legalism of the Puritans and their spiritual descendants. But even in their stern legalism, these Christians demonstrated a strength of character, a profound integrity, an obey-God-rather-than-men resolve, that compels our admiration. Some of us carry the DNA of those godly pioneers in our bodies; all of us have the privilege of accepting the heritage of their moral fiber in our Western culture.

“All these people were still living by faith when they died. They did not receive the things promised; they only saw them and welcomed them from a distance, admitting that they were foreigners and strangers on earth. People who say such things show that they are looking for a country of their own. If they had been thinking of the country they had left, they would have had opportunity to return. Instead, they were longing for a better country—a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he has prepared a city for them” (Heb. 11:13-16).

My ancestors settled near Salem, Massachusetts, emigrating there as Puritans, fleeing The Book of Sports style of Christianity. They risked beatings, fines, and imprisonment by converting to Baptist beliefs. They moved to Rhode Island, which had the first Seventh-Day Baptist congregation in America; then to New Jersey, where they formed a town and congregation. The Sabbatarians shared their Baptist minister with a first-day congregation. That branch stayed Seventh-Day Baptist until the twentieth century. Sabbatarianism skipped two generations (who were Methodists), and my parents became Seventh-day Adventists in 1964.

* www.greydragon.org/library/playingbowls.html.

Christy K. Robinson is a self-employed editor, author, music teacher, and church keyboardist. Her historical books and blog articles are related to religious liberty.