The world was stirred with alarm on March 8, 2014, when Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, with 227 passengers and 12 crew aboard, disappeared from all radar tracking. Nothing in the almost two years intervening has brought consolation to those bereaved by that disappearance, or peace of mind to administrators of Malaysia Airlines.

The experience of such a loss of human life on a daily basis for an entire year would be regarded as an intolerable horror demanding to be both explained and halted, particularly if the daily loss was every day suffered by the same airline with passengers all from the same country. This truth gives but a partial idea of the tragedy of racial differences in health in the United States. Not 239 but 265 Black (or African American) people die prematurely every day, a total of almost 96,800 deaths recorded per year that would not be if Blacks had the same death rates as Whites.

Not only are the death rates for Blacks elevated for most of the leading causes of death, but Blacks get sick at younger ages, have more severe illnesses, experience poorer quality of care, and die sooner than Whites. In a classic study, Professor Arline Geronimus of the University of Michigan analyzed national data to study the relationship between a mother’s age at the birth of her first child and health outcomes for her baby. Most people would expect infant death rates to be lower if a woman waited until her 20s to become a mother. Professor Geronimus found that infant mortality was lower for White and Mexican American women who had their first baby in their 20s compared to those who were teen moms. Stunningly, the opposite was true for Blacks and Puerto Ricans who lived in the continental United States. Among these women the infant mortality rate was lower among 15- to 19-year-olds than for those women who delayed having their first baby until they were in their 20s.

Geronimus proposed the “weathering hypothesis” to make sense of these findings. It argues that for minority group members living in bad environmental conditions, chronological age captures not only how long they have lived, but also the length of exposure to unhealthy environmental conditions, the cumulative adverse impact of exposure to these multiple social disadvantages, and therefore how physiologically compromised the human organism has become.

Research reveals that compared to Whites, Blacks are more likely to experience major hardships, conflicts, and disruptions such as crime, violence, material deprivation, loss of loved ones, recurrent financial strain, relationship conflicts, unemployment, and underemployment. Scientific evidence also indicates that the wear and tear because of exposure to chronic stressors is consequential for health.

Recent studies provide striking examples of early health deterioration of Blacks. A multicity study found that new cases of heart failure before the age of 50 were 20 times more common in Blacks than Whites. Other studies show that Blacks require dialysis or a kidney transplant at younger ages than Whites and have a higher incidence of end-stage renal disease at each decade of life. Hypertension also occurs earlier in Blacks than Whites, with 63 percent of Black persons age 60 or younger having hypertension compared to 45 percent of Whites.

This accelerated aging among Black adults is evident across a range of biological systems. One national study found a 10-year gap in biological aging between Black and White adults. This study used a global measure of biological dysregulation that summed 10 indicators of subclinical status (such as blood pressure, inflammation, glycated hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine clearance, triglycerides, and cholesterol). It found that at each age group, Blacks reached a biological profile score that was equivalent to that of Whites who were 10 years older!

Researchers have also used telomere length as an overall marker of biological aging at the cellular level. (Telomeres are sequences of DNA at the end of the chromosome that protect against DNA degradation.) A study of middle-aged women found that at the same chronological age Black women had shorter telomeres than White women that corresponded to accelerated biological aging of Black women of about 7.5 years.

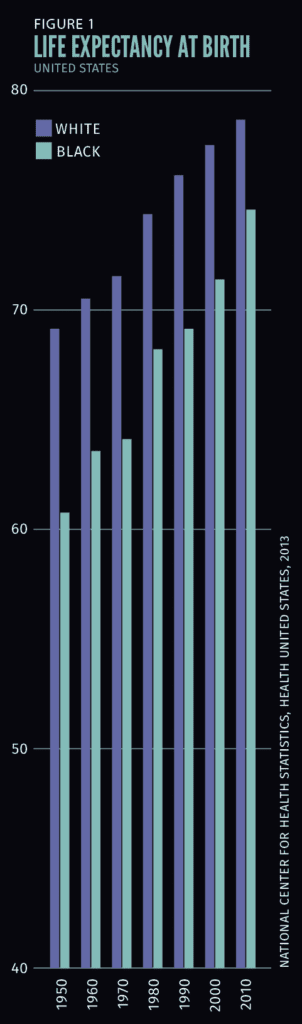

Life expectancy data illustrates the persistence of racial disparities in health over time. In 1950 Blacks had a life expectancy at birth of 60.8 years compared to 69.1 years for Whites. Life expectancy has improved for both groups, so that according to 2010 data, the racial gap has narrowed to be only half (about four years) of what it was in 1950. However, a four-year gap in life expectancy is large. It took Blacks until 1990, some 40 years later, to achieve the level of health Whites enjoyed in 1950, and current estimates are that it would take more than 40 years to close the current four-year gap between Blacks and Whites.

Group differences in hypertension offer a good illustration of the limits of biology to explain America’s persistent racial disparities in health. The important role of genes as determinants of health led some to explain racial differences in health as a matter of underlying genetics, with the large Black-White differences in hypertension in the U.S. seen as exhibit A.

However, an international comparative study of hypertension among West Africans in Africa and persons of West African descent in other contexts found a stepwise increase in hypertension as one moved from rural to urban Africa, to the Caribbean, and then to the U.S. Persons of African descent in the U.S. had hypertension levels that were twice as high as Blacks in Africa. Instructively, Whites in the U.S. have higher rates of hypertension than Blacks in Africa. Again, African Americans have higher rates of hypertension than Whites in some European countries such as Sweden and Italy, yet have lower levels than Whites in other European countries such as Germany and Finland. These patterns highlight the potential of social, cultural and environmental factors as contributors to health.

Recent reports from the U.S. Census Bureau document that racial differences in socioeconomic status (SES) remain large. In 2013, for every dollar of income White households received, Hispanics earned 70 cents and Blacks earned 59 cents. Incredibly, back in 1978 Blacks also received 59 cents for every dollar that Whites earned.

Even more stunning is the category of racial differences in wealth: in 2011 Black households in the U.S. had six cents of wealth and Hispanic ones seven cents for every dollar of wealth that Whites had. Because SES is among the most consistent determinants of variations in health in the world, these large racial differences in SES are important contributors to racial disparities in health.

Although racial differences in SES account for a substantial part of the racial differences in health, racial disparities in health typically persist, although reduced, at every level of SES.

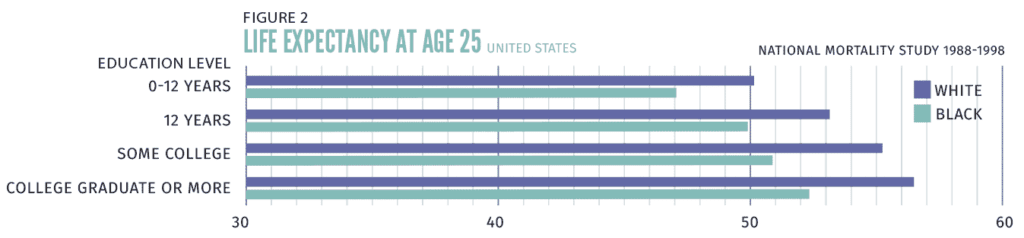

Figure 2 illustrates this with national data on life expectancy at age 25. The average White adult at age 25 will live five years longer than the average 25-year-old African American. However, for both Blacks and Whites, the gap in life expectancy by education is larger than the overall Black-White difference. College-educated Blacks and Whites live 5.3 and 6.4 years longer, respectively, than those who have not graduated from high school. For both racial groups, as education increases, health improves in a stepwise manner. But there are Black-White differences in life expectancy at every level

of education, with these differences being larger for Black and White college graduates (4.3 years) than for those who have not completed high school (3.4 years).

Impressive evidence documents the persistence of discrimination in U.S. society. In one study two Black males and two White males were given identical résumés and sent to apply for advertised jobs. One of each pair indicated that he had served a prison sentence for cocaine possession. The study found that whether Black or White, if one had a criminal record he was less likely to be called back for a job. Stunningly, the study also found that a White male with a criminal record was more likely to be offered a job than a Black male with a clean record. Research has documented racial discrimination in virtually every area of life.

Racial discrimination affects African American health in multiple ways.

First, a landmark report entitled Unequal Treatment, from the Institute of Medicine in 2003, documented that pervasive discrimination in medical care in the U.S. leads to fewer procedures and poorer quality medical care for Blacks and other minorities compared to Whites. These inequalities in care contribute to racial disparities in the severity and course of disease.

Second, residential segregation by race, a historic legacy of institutional racism, has resulted in most Blacks and Whites in the U.S. living in areas that vary dramatically in neighborhood quality and living conditions. Where one lives in turn affects access to quality education, employment opportunities, and medical care.

Third, minority group members are aware of at least some experiences of discrimination, and such incidents have been shown to lead to increased risk of a broad range of disease outcomes, preclinical indicators of disease (e.g., inflammation, visceral fat), and health risk behaviors.

The Scriptures are clear that God wants His children to enjoy good health (3 John 2). But for many African Americans, other economically disadvantaged and socially stigmatized populations in the U.S., and nondominant racial/ethnic groups in other societies such as Australia, Brazil, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, challenges in terms of health are quite similar.

Moreover, Americans overall are far less healthy than we could or should be. A 2013 Institute of Medicine report indicated that even college-educated Americans with healthy behaviors and health insurance had worse health than their peers in other industrialized countries. The witness of Seventh-day Adventists through the health message that God has been calling His children to live and to share for more than 100 years would be timely just now. Adventists should seriously embrace, practice, and implement those principles of comprehensive health ministry as outlined in Isaiah 58.

It would mean that as we give sustained and appropriate attention to enhancing the physical and mental health of all, we would contribute to reducing the large gaps in health by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

David R. Williams is the Florence Sprague Norman & Laura Smart Norman professor of public health at Harvard University.