What’s wrong with Old Testament prophecy? Nothing! In fact, it’s because prophecy is so good that God gives us more of it in the New Testament. It is His heart to give good and perfect gifts (James 1:17).

For many faithful Bible students, prophets and prophecy are somewhat more strongly associated with the Old Testament than with the New Testament.1 But the consistent listing of the gift of prophecy among the church’s spiritual endowments helps us to see it as no less prized in the New Testament church than it was with Old Testament Israel (1 Cor. 12:7-11, noting verse 10). The New Testament church clearly thought that prophecy was a good thing. While comparative lists of spiritual gifts are not a feature of Old Testament Scripture, the location of “prophecy” high up on New Testament lists of spiritual gifts emphasizes the great esteem it enjoyed in the early church; in an ordinal list, prophets are named second to apostles (verse 28); elsewhere, prophecy heads the list in Romans 12:6-8, and is second in Ephesians 4:11.

Prophecy works in the New Testament in the same way that it does in the Old Testament, if we judge by the Bible’s earliest definitions of prophetic function. Enoch, seven generations from the first man, Adam, is the earliest human to receive the identification of “prophet,” though we must credit the New Testament with awarding the honorific (Jude 14, 15). Next labeled in historical lineage, Abraham is so named by God Himself (Gen. 20:7), but without any clear articulation of what prophets do.

Keeping God’s words echoing means much more than merely repeating Egyptian or Hebrew vocables.

The earliest explicit introductions to, and depictions of, a prophet’s work come from Moses as he relates to God’s summons to discharge a specific assignment. God’s effort to extract him from Midian’s desert and return him to service in Egypt as liberator of His people opens up the window to what prophecy is and what prophets do: the God who “is a consuming fire” (Deut. 4:24; Heb. 12:29) confronts Moses with the miraculous spectacle of fire and no consuming (Ex. 3:1-3).

However startling that would have appeared, it seems that God would also have us notice something else. There is present another phenomenon that He would have us recall perhaps even more clearly: not sight, but sound—the sound of words, of echoing words. Prophecy, as definable from this early instance, is words that are echoed. Echoes are what God will not let us forget.

In fact, echoing God may be the supreme prophetic function: Moses will tell Aaron what to say (”put words in his mouth”) once God has told Moses what needs to be said. Aaron will then relay Moses’ words from God to the people of Israel, or whomever God has prepared them for. As God Himself explained to Moses: “I will help both of you speak. . . . He [Aaron] will speak to the people for you [Moses], and it will be as if he were your mouth and as if you were God to him” (Ex. 4:15, 16). What we may call the “prophetic proclamation chain” exhibits a specificity that God deems necessary: Moses will echo God, and Aaron will echo Moses.

Prophets of New Testament times understood and celebrated this specificity just as well as their Old Testament antecedents. The early articulation, “The Lord says thus,” which becomes predictably familiar with Old Testament respondents to God’s call into prophetic service,2 is spoken with no less authoritativeness among New Testament prophets, because they know that their commissioning God means for His spokespersons to utter “His words”—a phrase that we shall clarify—to their audience, rather than words born of their personal genius or some other inspiration.

In Tyre Paul hears from disciples “through the Spirit” that he is not to go to Jerusalem (Acts 21:4). Even if the disciples are not labeled prophets, we are told that it is the Spirit who is the authority of their utterance, the same Spirit who inspires all prophetic utterance (2 Peter 1:21). Agabus is labeled, and he says, “Thus says the Holy Spirit” (verse 11, NKJV).3 Prophecy was authoritative in New Testament times because it conformed to the same divinely imposed requirements of Old Testament times for qualifying as authentic.

At the same time, and importantly so, keeping God’s words echoing means much more than merely repeating Egyptian or Hebrew vocables Moses may have heard God utter. God’s most important Old Testament declaration, Exodus 20:1-17,4 gives good illustration of this truth. The Ten Commandments are twice identified as “10 words,”5 though the fourth of the 10 alone contains either 35 or 56 words, according to two different and well-established methods of counting Hebrew words. The phrase “10 words” allows us to clarify what God means by “His words.” For it is surely not God’s intent that we haggle over consonants and vowels, phonemes and syllables, numerical or numerological traditions. It is His determination that we strive to fathom and apply the particular ideas communicated in His commands.

In the case of the Ten Commandments He wants us to understand and cooperate with Him on ideas about idolatry and blasphemy, respect and obedience, greed and selflessness. The prophetic proclamation chain is no meaningless ritual echoing of sounds. It is meaningful communication of ideas from God to human audiences. It is getting the message out, whether by word or by drama: Old Testament Jeremiah buries and later digs up a linen waistband (Jer. 13:1-11) to dramatize God’s message against the pride of Judah and Jerusalem; New Testament Agabus binds himself with a belt (Acts 21:11) to dramatize his prophecy that Paul will be arrested in Jerusalem.

New Testament prophecy, like its Old Testament antecedent, communicates content, data from heaven, be it on contemporary issues or events in the near or distant future: Moses warned Egypt’s pharaoh of imminent judgment;6 Peter warns his contemporaries, and generations since, of final judgment (2 Peter 3:10). Old Testament prophetic voices demanded moral living (Isa. 55:1-3; Micah 6:8); New Testament prophets also declare God’s will for His people’s everyday living (Rom. 12:9-21; 2 Peter 3:11).

Often enough, New Testament prophecy takes up (echoes) an issue already addressed in the Old Testament, either in reiteration, expansion, or fulfillment of its Old Testament predictions: Every chapter ofthe Revelation of Jesus Christ, the final New Testament book, is better understood through studying the Old Testament book of Daniel: the book of Revelation connects to and significantly expands upon Daniel’s explanations of world history, and notably, his end-of-time sanctuary and judgment message.7

At other times, a New Testament prophetic statement highlights the typical function of a historical Old Testament event—Noah’s times and the days of Sodom and Gomorrah are types of the end-times (Matt. 24:37-39; Luke 17:26-37). Sheer familiarity with the scope of Jesus’ teachings may keep secular minds and even believers from realizing how consummately prophetic He is. His statements about His future return to earth include brief parables, longer sermons, responses to hostile queries about His kingdom or royalty, or sympathetic questions inspired by admiration of Herod’s temple,8 with the varied literary genres involved not mutually exclusive.

At other times, a New Testament prophetic statement highlights the typical function of a historical Old Testament event—Noah’s times and the days of Sodom and Gomorrah are types of the end-times (Matt. 24:37-39; Luke 17:26-37). Sheer familiarity with the scope of Jesus’ teachings may keep secular minds and even believers from realizing how consummately prophetic He is. His statements about His future return to earth include brief parables, longer sermons, responses to hostile queries about His kingdom or royalty, or sympathetic questions inspired by admiration of Herod’s temple,8 with the varied literary genres involved not mutually exclusive.

Apart from these climactic presentations, His predictions involve a variety of grand happenings treated tersely and unpretentiously: Nathanael will see greater things than he has so far (John 1:50, 51); the centurion will find his servant healed when he gets home (Matt. 8:13); some of the disciples will soon experience a glimpse of the glory of His future kingdom (Matt. 16:28; Mark 9:1; Luke 9:27); the temple and the city of Jerusalem will fall (Matt. 24:2; Luke 21:20-24); He will be glorified as a result of Lazarus’ illness (John 11:1-4); Lazarus will come back from the grave (verse 23); He [Jesus] will give His followers eternal life (John 6:27); believers in Him will never hunger, thirst, or die (John 4:14; 6:35, 50, 51; 11:25, 26); they will go free in the judgment (John 3:14-18); He will resurrect His followers at the end of the age (John 6:40, 44); there will actually be two resurrections at the end of the age, one for life and one for punishment (John 5:28, 29); His enemies will eventually arrest Him (Luke 13:31-33); they will arrest Him today—the hour “has come” (John 16:32); His disciples will all be undone (“offended”) that night (Matt. 26:31; Mark 14:27; Luke 13:27); one of His disciples will prove a traitor (John 6:70, 71; 13:21, 26); Peter will deny Him (John 13:38); He [Jesus] will be crucified (John 12:32, 33); He will die for the sake of His followers (John 6:51; 10:11-18); He will spend three days and nights “in the heart of the earth” (Matt. 12:40); He will raise Himself from the grave (John 2:19); He will return to heaven (John 7:33, 34); people will see it (John 6:62); He will be gone only for a little while (John 16:17-23); His followers will be hated (Luke 21:17), maltreated (Matt. 23:34; Luke 21:12), even martyred (Luke 11:49; John 16:2-4); He and the Father will send the Holy Spirit (John 14:26; 15:26); the Spirit will convict people of their guilt and lead them to truth (John 16:8-15); some urban dwellers (from Bethsaida, Capernaum) will fare worse than others (from Sodom and Gomorrah, Tyre and Sidon) in the final judgment (John 10:14, 15; 11:21-24)—a monumentally incredible remark if by any being but God Himself.

After Jesus’ return to heaven, the Holy Spirit continued selecting people to be prophets, a job that is His unique responsibility, depending on spiritual rather than technical or academic considerations. God’s Word then echoes through the prophets’ ministry: they speak as He moves them (2 Peter 1:21). As in the Old Testament, some of them produced Bible books—the four Gospel writers, Peter and Paul, etc. Others, such as Agabus and the evangelist Philip’s daughters (Acts 21:8-10) did not. And because prophetic qualifications are wholly a divine determination, Christians throughout history have always needed to depend on God’s guidance in deciding whether or not to accept a given individual’s prophetic claims.

Through the centuries individuals have claimed to possess the prophetic gift, and followers of Jesus have had to determine the validity of their claim. The Bible gives sound instruction on how this is to be done: the witness of true prophets will be in accordance with God’s law and with the work of earlier prophets of God (Isa. 8:20; Rev. 19:10). Even accurate predictions of future events do not count if a prophet’s teaching contradicts the principles of God’s law (Deut. 13:1-5). Jesus warned of the critical role of false prophets in Satan’s commitment to deceiving as many as possible (Matt. 24:5, 11).

Through the centuries various men and women from Asia to America have claimed the gift: Montanus, as well as Priscilla and Maximilla, in the second century after Christ; Mary Baker Eddy and Edgar Cayce in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the United States. Second-century Montanus believed that the church’s access to spiritual gifts is to be continuous through time. Though his case continued to be debated for centuries after his time, he is to be admired for his yearning after the simple godliness and spiritual anointing of the Apostolic Era.

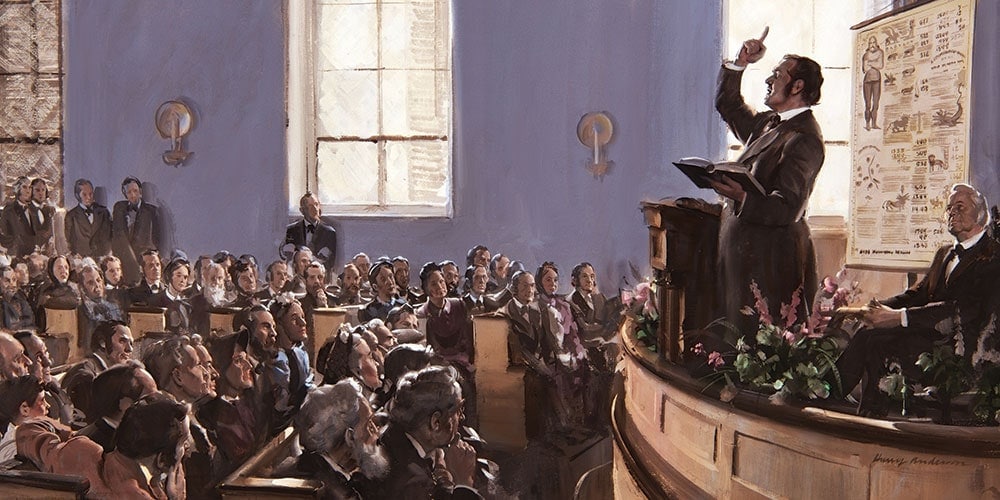

That yearning for holiness was a character trait of a nineteenth-century child, Ellen Gould White (née Harmon), from the time she was 11 years old. With others who were many years older, White passed through what came to be known as the Great Disappointment of October 22, 1844: on that day Bible students in many parts of the world expected Jesus to return to earth. When He did not appear, they were profoundly disappointed.

In the New England region of the United States three different groups emerged from the Disappointment: one group consisted of people who rejected the Bible as a source of reliable predictions; a second group persistently set new dates for Jesus’ return, each one passing unceremoniously; a third group reviewed the biblical evidence to determine where they had blundered in interpretation. Continued study clarified their error and deepened their conviction on the reliability of Jesus and of God’s Word. It also led them to other significant Bible truths: death as a completely unconscious state; the second and investigative phase of God’s salvation program, equivalent to the once yearly, Day of Atonement rituals connected with the Most Holy segment of the sanctuary service. That new phase of God’s thoroughly organized program involves a review of cases, an “examination of character, of determining who are prepared for the kingdom of God.”9

On August 30, 1846, Ellen married James White. Along with retired sea captain Joseph Bates, the Whites are recognized as the principal nineteenth-century founders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Over a period of almost 70 years, from 1844 until her death in 1915 at the age of 87, White received more than 2,000 visions and produced more than 100,000 written pages of work.

The development of the Adventist Church is inextricably bound up with her ministry. Her individual, familial, and personal life as woman, wife, and mother; her professional life as author, gospel preacher, educator, Bible student, and theological thinker; her agitation for social justice, Christian education, temperance, and, more broadly, the practical necessity and spiritual profits of healthful living: all of these, through the testimony of her peers and the study of her writings, continue to be available for public and academic scrutiny by anyone interested in investigating the claim that she represents a nineteenth- to twentieth-century manifestation of the spiritual gift of prophecy. Adventists believe that her life and body of work amply validate the New Testament prediction that spiritual gifts, prophecy included, will be present to work in Christ’s church “until we all reach unity in the faith and in the knowledge of the Son of God and become mature, attaining to the whole measure of the fullness of Christ” (Eph. 4:13).

That day is near. Praise God.

Lael Caesar is an associate editor of the Adventist Review.