The Bible’s first five books are a unit called the Pentateuch. The third of those five has the Hebrew name Wayyiqra (the text’s first word). Its English name, derived from the Greek (Leuitikon), comes to us as a direct transliteration of the Latin Leviticus, and means “Levitical service” or “things about Levites.” So what might a book about Levites have to do with Jesus?

The Levites were descendants of Jacob’s third son, Levi. Jesus was no descendant of Levi. He was a Judahite, something the Gospels of Matthew and Luke explain from the outset. Their genealogies, the New Testament’s most extended, both detail Jesus’ Judahite ancestry. Matthew’s first word establishes Him as David’s and Abraham’s Son (Matt. 1:1). Then, beginning with Abraham, he traces Jesus’ lineage all the way to “Jacob the father of Joseph, the husband of Mary, . . . [who] was the mother of Jesus” (Matt. 1:16).

Was Matthew introducing Jesus as Joseph’s biological son? Of course not. He chose his words to avoid any such misunderstanding: unlike standard genealogical linkage (e.g., Judah is Perez’ father, or Jesse is King David’s father), Joseph is not anybody’s father. He is the husband of Jesus’ mother.

Matthew knew the difference better than others; he got it from an angel of the Lord! The angel told Joseph (speaking of Mary, the baby’s mother), “What is conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit” (verse 20). But Matthew’s Spirit-guided Gospel genealogy served social and supernatural objectives in tracing Jesus through Judah. His genealogy ensures that Mary’s baby will stand forever as the ultimate challenge of all human conception. Mary’s baby is the unfathomable mystery in flesh and blood of the Lion born to Judah’s tribe, who is God’s own sacrificial Lamb slain from the world’s foundation; David’s and his father Jesse’s Root, who is also David’s Offspring; the priest forever, but of Melchizedek’s order; the Maker and Sustainer of all things, visible and invisible, material and logical, who is Creator God, the Word made flesh to save the world.1

When this unfathomable Jesus lived among us, God Incarnate, He sometimes pointed people to Leviticus. Some students of His life find it more hostile to, than supportive of, things about Levites. They may acknowledge that Leviticus includes much besides slit animal throats and roasted grain. It includes ethical teachings consistent with Jesus’ own elevated moral values. But they find the book’s elaborate ritual systems undesirable and dispensable. These scholars read Jesus’ fierce criticism of the ritualists of His day as denouncing everything such people stood for.

Their critique would make them authorities on what may stay in or be cut out of the book. But the location of this book at the heart of the Bible’s foundation unit hardly supports claims of even its partial dispensability or piecemeal application. Instead, its central location suggests its crucial importance to the God who authored the book.

The Israelites were mostly stuck on rituals and void of morals. They needed more lessons on integrity than they did on ritual process.

Abraham’s descendants, the book’s first recipients, were God’s chosen vehicle to channel His salvation history to all humanity, a history that climaxes with the life and passion of Jesus, the seed promised to Abraham who would bless the whole world (Gen. 12:3; Gal. 3:16). Much of God’s original purpose for His people, and about the kind of character He meant for them to develop as individuals and as a nation, is laid out in Leviticus.

One simple way of appreciating that purpose and character is comparing two names given to the five-book grouping to which Leviticus belongs: “Pentateuch” simply means “five scrolls.” “The Torah,” an older identification, states something meaningful about the books: they are “the teaching” or “the instruction.” The Torah is God’s unique instruction manual to His people Israel, provided to them through His genius servant Moses. Leviticus, its central teaching book, instructs on what, how, and who Israel was supposed to be, and why: “Be holy because I, the Lord your God, am holy” (Lev. 19:2). “Be holy, because I am the Lord your God” (Lev. 20:7).

God selected the Levites to lead out in His drama of holy being. There was hardly a thing they weren’t running: Moses—unique leader; Miriam—prophet and celebration leader; Aaron and his descendants—the priests; Kohath, Gershom, Merari, and their families—managing transport of the portable church called the tabernacle (mishkan), or sanctuary (miqdash). Church, work, peace, and even war: it was Levites all the way.2 The tribe’s link to all of Israel’s sacred rituals bestowed on them yet another honor: they are the only one of Israel’s 12 tribes to give its name to one of the Bible’s 66 books, namely, Leviticus, “things about Levites.”

Leviticus includes a lot of description of Levites’ work, which some have attempted to use, as mentioned before, to set the book against itself: setting ritual material against ethical material—chapters 1-16, more or less, against chapters 17-26. But the opposition of ritual to ethics makes a loser of both: ritual that is ethically void is no more rewarding than ethics that is practically irrelevant. The book of Leviticus includes both didactic rituals and practical ethics: witness, supremely, the life, ministry, and passion of their original Lawgiver, Jesus Himself, a fact worth emphasizing. For “it was He [Christ] who gave the law to Israel.”3

He who presented the instructions of Leviticus to Moses during a month of lectures at their meeting tent later came to Earth to magnify those teachings.4 Through 33 and a half years of love and inexhaustible service, sacrifice and singular passion, life and undeserving death, resurrection from hell and guarantee of soon return, Jesus, Author of Israel’s teaching, fulfilled its potential infinitely—surprising, delighting, dismaying, frustrating the eyes and ears, hearts, and minds that were privileged to witness His incarnation of Torah meaning.

As often as He could, He pointed to Leviticus to validate His actions and arguments, drawing as much on Levitical ritual systems as He did on Levitical ethics. Altogether, the four Gospels contain 40 references that produce 44 evocations of the book5—some brief, some extended—that connect Jesus’ life and teaching with words, ideas, rituals, and morals from Leviticus. In 23 of those 44 instances, Jesus actually quotes Leviticus. He needed to go back there for the sake of His people who had lost their way and needed His help in redirecting their steps through repairing their thinking.

The book itself never leaves any doubt as to the gloriously exalted status God intended for His people. Having extracted them from the clutches of their slave masters, He settled them in around the base of a desert mountain for a yearlong tête-à-tête, giving them some space to appreciate how much He cared about them; to reflect on what had just happened; to understand how, and why: “You yourselves have seen what I did . . . , and how I carried you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself” (Ex. 19:4).

He shared with them what He was about to do for them: “Out of all nations you will be my treasured possession” (verse 5). This was the beginning of their training toward unimprovable ends: “You will be for me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (verse 6). He would maintain the same level of interest and effort He had already invested to see them through to stellar success.

Everything depended on their willingness: “if you obey me fully and keep my cove

nant” (verse 5). God was interested in their perspective, in cooperation and mutuality; nothing would be by force or intimidation.

Recently liberated slaves found it hard to believe, but their God was insistent. Even before He gave Moses the material contained in Leviticus, He described their splendid future: “Youwill be for me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (verse 6). He was giving them the gospel: “The gospel is given in precept in Leviticus.”6

But it hadn’t quite worked out. They had become convinced that their best option would be mimicking their neighbors. They lodged a petition with their God-appointed leader: permission to mimic their neighbors (see 1 Sam. 8:4, 5). Something better than the gospel. By the time Jesus arrived, being like the neighbors had dragged them back into subjugation, so that their overriding fantasy was of a Moses who would liberate them again, and restore their independence and status (Matt. 20:20, 21). Jesus had come about an exodus too (Luke 9:28-31); He was the fulfillment of a prophecy Moses had given them (Deut. 18:15). But it wasn’t one that caught the leaders’ interests.

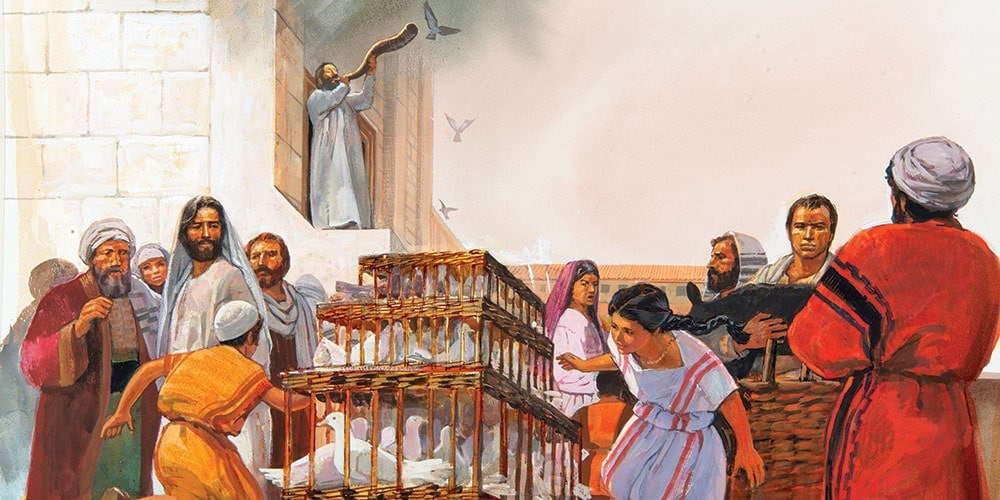

They were mostly stuck on rituals and void of morals. They needed more lessons on integrity than they did on ritual process. They must have known how to reinstate lepers to society once the skin disease that had shut them out of society had disappeared. So Jesus sent them lepers He healed, respecting procedures He had set up with Moses a millennium and a half before: “Show yourself to the priest and offer the sacrifices that Moses commanded for your cleansing, as a testimony to them” (Mark 1:44; see also Luke 17:14).

The ritual of cleansing mattered. He Himself had prescribed it. But its lessons about purity were always supposed to have gone beyond the surface and skin diseases. Jesus could teach, as no one else ever could, about the depth of cleansing available beyond skin deep, cleansing He Himself could provide, and only He, the “washing of rebirth” (Titus 3:5), the new start, the truly clean and flawless life that ritual systems could graphically symbolize but never actually accomplish, because, though “it is impossible for the blood of bulls and goats to take away sins,” nothing is impossible with God (Heb. 10:4; Matt. 19:26): His touch gave life and healing to the untouchable, but never brought defilement to Himself, because even becoming sin itself does not taint His righteousness (Mark 6:56; Luke 5:13; 2 Cor. 5:17). Indeed, it is only because of His sinlessness, while numbered with the transgressors, that He may intercede for us transgressors (Isa. 53:12).

God did not mind “sacrifices and offerings, burnt offerings and sin offerings”; after all, “they were offered in accordance with the law” (Heb. 10:8). But they were not enough (verses 1-5). The sacrifices taught the horrible carnage sin causes. The instructions for lepers taught the repugnance to God that sin provokes. And the sacrifices taught humanity’s need for help from beyond ourselves: “all our righteous acts are like filthy rags” (Isa. 64:6). More expensive sacrifices make no difference; nor does roasting adorable babies (Micah 6:7)—this is neither show and tell, nor pity party extraordinaire. Leviticus taught our need for a substitute that is perfect.

On the other hand, Levitical ethics was too much: Jesus’ exegesis of Mosaic ethical positions was both noble and overboard: “Love your neighbor as yourself” was Levitical, all right (Lev. 19:18). But would you do it the way your Father in heaven does it? That’s your reference point; or as Jesus put it just before His passion, would you love as I love you (John 13:34)? It seems, in the end, that everything about Leviticus, from sacrifice to ethical pronouncement, leads to the same conclusion: the book is fine, after all. Why? Because it teaches our true need.

The book “about Levites” says we need more than an Aaron or Moses, or a Levitical priesthood: we need one to intercede for us, “not on the basis of a regulation as to his ancestry but on the basis of the power of an indestructible life” (Heb. 7:16). We need Jesus.

Lael Caesar is an associate editor at Adventist Review Ministries.