Spoken language was highly important to Jesus: “tears were in His voice as He uttered His scathing rebukes”; and He “exercised the greatest tact, and thoughtful, kind attention in His intercourse with the people.”1 Mark reports that “common people heard Him gladly” (Mark 12:37, NKJV).2 The people of Nazareth wondered “at the gracious words which proceeded out of His mouth” (Luke 4:22, NKJV).

If words themselves count for so much, with what zealous attention should we consider the impact of song, where the symbolic meanings of words are richly enhanced by the emotional power of music and poetic form. Music itself admits of no literal translation into “meaning,” but instead provides an experience to be relished (or despised!). And while it cannot be absolutely reduced to verbal interpretation, it nevertheless carries a message (primarily emotional) by its very nature.

Indeed, research shows that music, even apart from any words that may accompany it, preempts and synchronizes the listener’s brain waves, “entraining” them with an immediacy that overrides mere verbal content. When the musical and verbal messages correlate, the impact is multiplied. If they are not the same, the musical impact consistently prevails over the rhetorical.

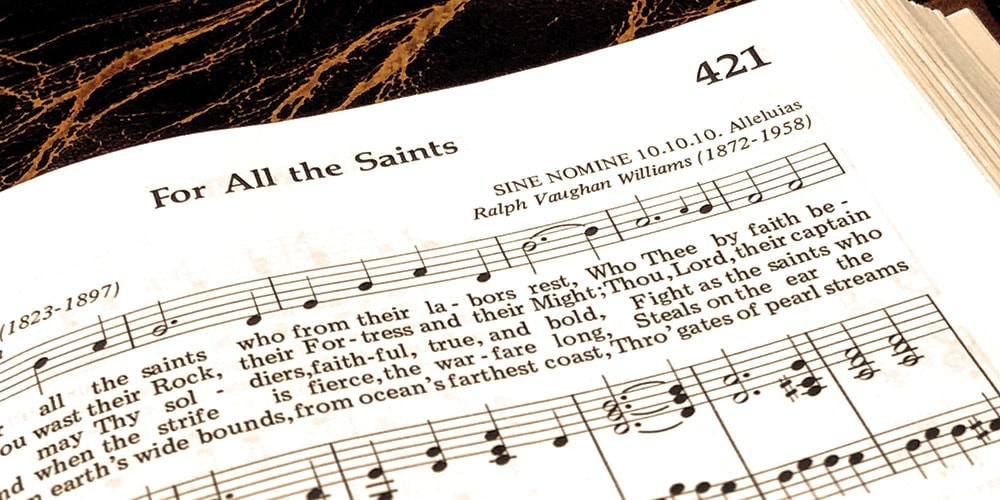

The Seventh-day Adventist Hymnal (SDAH) offers many fine examples of great pairings. The final victory of the redeemed, as William How described it in “For All the Saints,” fairly shouts in Ralph Vaughan-Williams’ vibrant tune, SINE NOMINE (no. 421). James Montgomery’s self-searching in “Go to Dark Gethsemane” finds appropriate expression in Richard Redhead’s GETHSEMANE (no. 157). And John Goss’s LAUDA ANIMA (No. 4) ably and amply supports Henry F. Lyte’s “Praise, My Soul, the King of Heaven.”

Not all possible combinations are as successful. The Church Hymnal, predecessor of SDAH, included three stanzas (out of 14!) that Charles Wesley called “Wrestling Jacob.” They were grossly mismatched with a subdued, funeral-parlor kind of tune—and Jacob’s terror-stricken grappling to survive disappears into thin air!

Good matches make good opportunities for new creative work. I have just arranged “Away in a Manger” for clarinet and cello. When any appropriate pair of artists plays this version, the accompanying words will come to life in many a listener’s mind.

There is always the possibility of creating an entirely new musical context for a hymn. Any hymn that begins with a dramatic “Alas” deserves significantly intense musical support (such as SDAH 163). My new setting, for choral purposes, includes the third and fourth stanzas omitted in SDAH that prepare effectively for the “but” that opens the final stanza.

Whatever the process, the goal is always the same: to enrich worshippers’ vocabulary of praise, of spiritual comfort, of devotion and commitment to the God whose love impels Him to sing over His own (Zeph. 3:17).

J. Bruce Ashton, actively retired from Southern Adventist University, Collegedale, Tennessee, continues to teach, perform, and create for God’s glory.