Almost every organized Christian denomination has a set of doctrines and associated practices, which it has corporately agreed to and which distinguishes it from other Christian churches and other religions. The Seventh-day Adventist Church is no different. Where many other Christian denominations adhere to a strict creed, Adventists take a more flexible approach, with what we call our Fundamental Beliefs.

The most famous of the formal creeds date back to the early church and shaped the very concept of what it means to be “Christian” and “heretical.” Seventh-day Adventist doctrinal declarations emerged recently. From where, then, came the “Fundamental Beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists”? This short article provides a brief overview of the development of Adventist doctrinal statements, drawing on recent work by historians of Adventism and research conducted by the General Conference Office of Archives, Statistics, and Research.

1

Even before the Seventh-day Adventist Church was founded, the men and women who would go on to establish it in 1863 were deeply antithetical to creeds. At a conference in Battle Creek, Michigan, in the autumn of 1861, at which foundational measures for the formal organization of the denomination were taken, one of the delegates, John N. Loughborough, declared: “The first step of apostasy is to get up a creed, telling us what we shall believe.”

2 This is often quoted as evidence of Loughborough’s resistance to organization, and his fear that Sabbatarians were taking steps toward creedalism and apostasy. The opposite is true. The point he went on to make was that the steps being proposed at the conference were not like those of the churches that had remained in “Babylon.” Loughborough’s words highlight the opposition to creeds among the new movement’s leaders.

For more than 160 years Seventh-day Adventists have affirmed the language adopted 40 years ago in the official preface to the church’s Fundamental Beliefs: “Seventh-day Adventists accept the

Bible as their only creed.”3

Yet that quotation comes from a lengthy statement of 28 beliefs, approved by a General Conference Session, which alone can amend the text. Seventh-day Adventists have published doctrinal declarations for more than a century. How can the existence of such documents be reconciled with the claim, proudly maintained from even before the denomination’s formal organization, that “Adventists have no creed but the Bible”?

The key to understanding Adventist attitudes historically and today lies in what the denomination’s founders understood a “creed” to be. For the forebears of this church, a creed was a permanent, unchanging statement of faith that cannot be challenged and cannot be amended. It was more than a statement of belief(s). A creed was formal, all-inclusive, inflexible, immutable, and, implicitly at least, coercive, since all members had to subscribe to it.

This, in the eyes of the founders of this church, was an unbiblical and illegitimate restriction on every Christian’s prerogative to search the Word of God and understand it for themselves. The Adventist pioneers were deeply concerned that adopting creeds discouraged people from studying the Bible—that the creed, not the Scriptures, became the final authority. Adventists believed that people of faith should not cease to search diligently for the truth.

As we shall see, the first Seventh-day Adventists

did see a place for summative statements of what they taught, describing who they were, what made them unique, and what Bible truths they had discovered and agreed on up to the time of publication. Such lists of beliefs were not universally binding. Internally, they helped to prevent the proliferation of teachings that were rejected as false and to facilitate their refutation. Externally, they helped Seventh-day Adventists clear themselves of false charges. They were a means to an end, there to serve Adventism, not to be its master.

In sum, the first Seventh-day Adventists rejected creeds as

prescriptive, but did see a place for descriptive statements of beliefs.

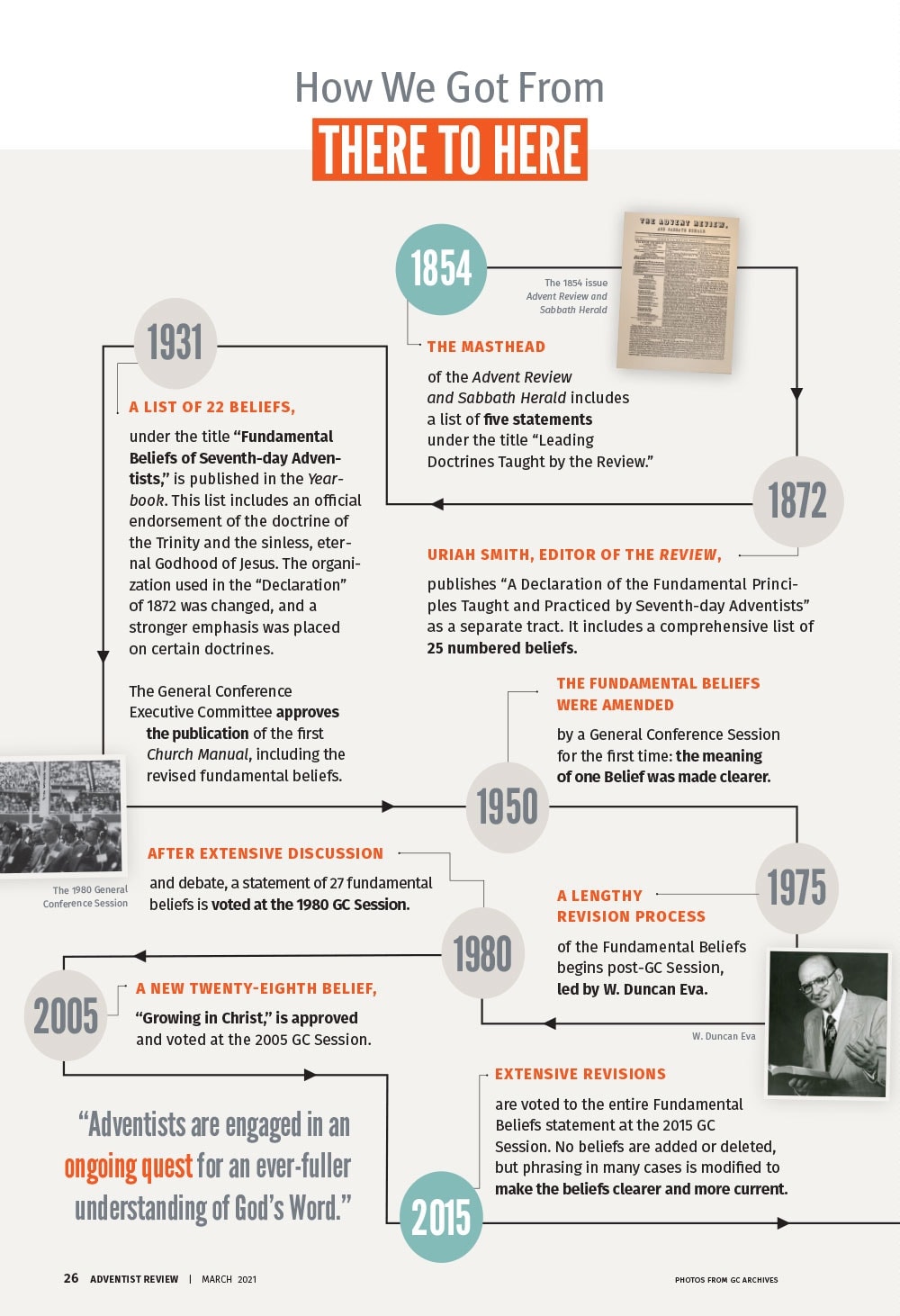

The oldest statement of doctrinal positions held by Sabbatarian Adventists predates the founding of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. For several months from the summer of 1854,

The Advent Review and Sabbath Herald (the journal that bound together the scattered and often isolated adherents of the embryonic movement, and that today is called Adventist Review) included under the masthead on the first page of each issue the heading “Leading Doctrines Taught by the Review.”4 There were only five (unnumbered), and the first was anti-creedal: “The Bible and the Bible alone [was] the rule of faith and duty.” The others concerned the enduring character of “The Law of God” and how the Second Coming and state of the dead were understood.

The experiment was relatively short-lived, but 18 years later came what can be seen as the first Seventh-day Adventist statement of beliefs: “A Declaration of the Fundamental Principles Taught and Practiced by Seventh-day Adventists.”

5 Written anonymously by Uriah Smith (editor of the Review) and published in 1872 as a separate tract by the church’s publishing house in Battle Creek, it comprised 25 numbered beliefs and was fairly comprehensive. Smith wrote in 1874 that “in presenting to the public this synopsis of our faith, we wish to have it distinctly understood that we have no articles of faith, creed, or discipline, aside from the Bible.” It was, he went on, no more than “a brief statement of what is, and has been, with great unanimity,” held by “our people.”6 Smith hoped to give the wider public a better understanding of the Seventh-day Adventist faith. The declaration was also intended to help identify and restrict the influence of people who, while claiming to be Seventh-day Adventists, sought to undermine doctrinal positions upheld by the denomination as a whole. Soon after the publication of Smith’s tract, James White (church cofounder) proposed that the newly established Battle Creek College (today’s Andrews University) offer “a thorough course of instruction in the fundamental principles . . . of Seventh-day Adventists.”7

The next major milestone came in 1931 with the adoption of 22 “Fundamental Beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists.” A major motivation for the preparation of this entirely new statement was, again, giving the public a frame of reference for understanding what Adventists believed.

One of the most notable changes from the previous version was official endorsement of the doctrine of the Trinity and the sinless, eternal Godhood of Jesus (beliefs 2 and 3). Other differences resulted from differences in how the document was organized—such as adding to the traditional understanding of Christ’s ministry in the heavenly sanctuary a stronger emphasis on His earthly ministry. The 1931 statement was commissioned by General Conference president Charles Watson, drafted by a small committee at the church’s world headquarters, and initially was not formally approved by a larger or more representative body of church leaders, at least not directly. It

was, however, approved for inclusion in the new Church Manual, which was first published in 1932, by mandate of the General Conference Executive Committee. The Statement appeared in both the Church Manual and the Seventh-day Adventist Yearbook thereafter.8 The text of the Church Manual was approved by General Conference Sessions from 1946 onwards, meaning that the text did receive official sanction (for example, in 1950, Belief 19 was amended by that year’s Session).⁹

The 1931 statement was apparently designed to articulate the basic tenets of Adventism for non-Adventists and thus to address key points of difference between Seventh-day Adventists and non-Adventists. It did not go into detail on other matters, except where church leaders sensed divisions among their church members and wanted to gently guide toward harmony. This was true, for example, of the statement about the Godhead.

More than 40 years later a revising of the 1931 statement was required for an official response to issues increasingly debated within the Seventh-day Adventist Church. There had been no belief statements dedicated to the creation of the world or to inspiration. In the 1920s and 1930s these had just not been matters on which there was any disagreement within Adventism. In the light of controversies emerging in the 1970s, some Adventists, particularly leaders at the General Conference, wanted the statement to clarify and rectify glaring omissions. This was the pronounced view of General Conference president Robert Pierson. Other leaders, such as Bernard Seton, associate secretary of the General Conference, were keenly aware that the 1931 “Fundamental Beliefs” had literary inadequacies, and lobbied for a redraft.

A lengthy process of revision began after the 1975 General Conference Session and was led by Vice President W. Duncan Eva, an experienced and diplomatic church leader who had served in leadership on three continents. Eva ensured that the church’s biblical scholars and theologians were fully involved in the process of drafting, which lasted more than three years, with multiple drafts, redrafts, reviews by church leaders around the world, and reviews by scholars. Eva chaired a series of committees that carried on the work of revision and updating and eventually proposed an entirely new statement. In 1979 the preliminary draft was presented to the General Conference officers, division presidents, and union presidents in North America.

10

The new draft statement had substantial changes, such as doubling the length of the doctrine of the Trinity, while entire new sections included beliefs about Creation, the Fall, the church, unity, the Lord’s Supper, Christian marriage, and the home. After more meetings involving church leaders and seminary professors, a version comprising 27 Fundamental Beliefs was put to the 1980 General Conference Session. After extensive discussion and debate, the statement was officially approved on the final day of the 1980 session.

At the 2005 GC Session, a new twenty-eighth Belief entitled “Growing in Christ” was added, in order to address the spiritual struggles faced by Christians, especially in parts of the world in which demonic power was a live issue. The new belief related such struggles to Jesus’ own victories during His earthly ministry, encouraging believers to stand firm in their faith and continue their growth in Christ.

At the 2015 GC Session, the statement as a whole underwent sweeping revisions in its phrasing. There were no changes or additions in the beliefs themselves; however, a comprehensive updating of the language was undertaken to make it clearer and more modern. This is not an option for the classic creeds of Christian tradition, such as the Nicene Creed and others.

While Seventh-day Adventists since 1860 have understood creeds to be unchangeable, they saw statements of fundamental beliefs as being acceptable, partly because they were open to revision. They wanted the freedom to modify their confessional statement so as to reflect more accurately progressive biblical revelation. When the denomination became convinced that one of its beliefs was in error (such as the semi-Arian understanding of the Godhead), Adventists collectively discerned it appropriate to amend their doctrine of God.

That said, it is important to note that the distinctive Seventh-day Adventist doctrines (what the denomination’s cofounder Ellen G. White called the Adventist “pillars,” or “landmark” doctrines), have never been substantially modified. Again, we have not always emphasized the same doctrines to the same extent. For instance, there was no need to include a statement about Creation in the 1932 statement, since there was no uncertainty about that doctrine. By the 1970s that was changing, and by 2015 it had changed again; and as a corporate church, we adapted how we explained and nuanced an unchanging doctrine.

Adventists are engaged in an ongoing quest for an ever fuller understanding of God’s Word. That quest reflects a truth widely recognized by Christian scholars: “Creeds become authoritative when they become the commonsense wisdom, the consensus of the Christian community.”

11 Creeds as classically conceived have little room for common sense and demand more than mere consensus. On the other hand, creedal-type statements, such as those adopted by Adventists over the years, give the community of believers the opportunity to respond to the continued prompting of the Holy Spirit.

The longstanding Adventist claim not to have a formal creed means that we do not have an inflexible statement that

defines Seventh-day Adventist beliefs and that cannot be altered, even in minor ways. What we do have are the Fundamental Beliefs, which describe what Seventh-day Adventists have agreed they believe, and which, while they have had the same core throughout Adventism’s history, have taken on different forms, have grown in number, and have been expressed in different ways.

We do not have a straitjacket that constrains Bible study, impeding the attainment of a deeper understanding of divine truth. Neither, to extend the metaphor, do we wear a motley, ill-fitting collection of multifarious theological rags. We have a made-to-measure yet flexible garment, well sewn, carefully and lovingly mended over many decades, that helps to protect us from the icy winds of doctrinal incoherence.

The “Fundamental Beliefs of Seventh-day Adventists” would be described by some as creed-like, but it is not a creed in the sense that we have historically understood the term. It is still the case that Adventists’ only creed is the Bible.

Historian

David J. B. Trim serves as director of the Office of Archives, Statistics, and Research at the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists, Silver Spring, Maryland, United States.