As principal of an Adventist elementary school in southern California, I often crossed paths with other school administrators at conferences, meetings, or workshops. After we exchanged routine pleasantries, the most commonly asked question was “So how’s your enrollment this year?”

This question, while casually lobbed, was wielded like a razor-sharp sword, cutting quickly into the heart of one’s efficacy as a principal. My response, I learned, would either cause my colleagues to nod with respect or raise their eyebrows in concern.

I always chafed at this snap judgment and began to feel quite defensive about my student population. Like most Adventist schools in the early 2000s, enrollment concerns dogged us; eighth-grade graduating classes were slowly dwindling; and even smaller kindergarten classes were coming in.

Are we the problem? I often mused to myself. Are we doing something wrong?

Well-meaning parents and school-board members seemed to think we were. “Perhaps if you had a more robust after-school program,” some suggested. “The school down the street is full to overflowing; they just added drama and photography to their curriculum,” noted others.

Was that it? If we changed our course offerings or bought more computers or taught dual-language classes—would our enrollment suddenly increase?

From this context I began my study about Adventist culture and school choice. My experience as a school administrator led me to believe that there was something else involved in parents’ decisions over where to enroll their children. For some Adventist families no sacrifice was too great to send their children to an Adventist school. For other Adventist families the local public school seemed to satisfy all their expectations. What was the difference? What made Adventist education necessary for some and expendable for others?

I hypothesized that Adventist culture played a significant role—that beyond tuition costs and educational offerings, something about one’s identity in the Adventist Church affected school choice. There are instruments that measure church attendance and religious dogma, but I needed something to gauge the knowledge of Rook strategy and haystack-building techniques. That index could then be examined in parallel with K-12 enrollment decisions.

So I started on this path to explore the relationship between culture and school choice. The first step required me to formally establish the existenceof a cohesive culture among Adventists in North America. In order to use it as a variable, I had to find a way to quantify Adventist culture. The world of academia demanded more than just my gut feeling or nostalgic anecdotes about Rook games and academy banquets.

I chose to use cultural consensus analysis, a methodology employed by social scientists and anthropologists, including William Dressler and Francis Dengah. This approach allows researchers to assess the degree of shared knowledge within a community, thereby determining the extent of agreement among its members.

I began by asking a sample of Adventists across North America to free-list characteristics or behaviors that they might see in traditional Seventh-day Adventists who lived according to the prescribed Adventist culture. Answers ranged from a vegetarian diet to Sabbath preparations to modest dress to an interest in music performance. These items were reduced to a cohesive list of 27 traits.

The process next required a second sample for a second task. Again, all were active and involved Seventh-day Adventists from across North America. These participants were asked to rank-order the 27 items that had been derived from the first sample’s responses. I sent them all cards with a trait written on each one and instructed church members to order them from most likely to least likely to be seen in a traditional Seventh-day Adventist.

The results of these two tasks provided the data necessary to run an inverted factor analysis, which produced an eigenvalue ratio of more than three to one. This value gave empirical evidence for a cohesive cultural domain among Seventh-day Adventists in North America. This alone was an achievement worth celebrating, or at least give a moment’s pause.

The ramifications of this discovery should not go unnoticed; that there is indeed statistically established proof of an Adventist culture is hugely significant and can provide a springboard for a multitude of other studies exploring different aspects of Adventist culture and lifestyle choices. (For a more complete explanation of the methodology and findings, see scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/142/ for the entire study.)

Because of my original intent to look at school choice, I took the Adventist cultural scale developed through the cultural-consensus-analysis process and embedded it into a survey instrument along with two additional validated scales: general religiosity and Adventist doctrine. The survey targeted Adventist parents who had K-12 school-aged children and was disseminated digitally in the summer of 2018 through social media, ministerial newsletters, church websites, and online church bulletin announcements. The survey was open for roughly one month, in which time more than 1,000 parents responded.

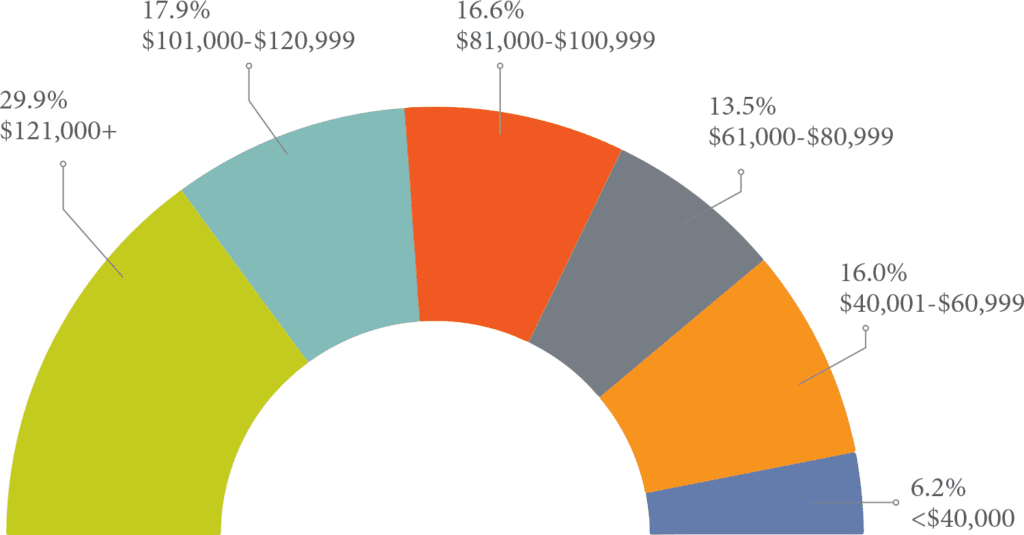

School Choice and Finances.While the bulk of the survey involved questions about religion, doctrine, and culture, the instrument also included basic demographic queries, including ethnicity, zip code, and annual income. Correlating socioeconomic status with school choice had not been the primary research question, but because tuition costs are so often part of discussions about Adventist education, it seemed worthy of time and attention.

The results from this study demonstrated that among Adventist families in North America who make between $40,000 and $120,000, there is no significant correlation between a family’s socioeconomic status and school choice. In fact, based on data from the survey, more families in the $40,000-$60,000 bracket chose Adventist schools than those who earned between $61,000-$80,000! (See Figure 1.)

Simply put, money may still be a factor in school choice. But according to this study, it is certainly not the most significant cause for enrollment decline in K-12 Adventist schools.

School Choice and Culture. The survey instrument had 13 questions that focused specifically on Adventist culture. These questions were developed based on statements taken from the aforementioned initial tasks of cultural consensus analysis. With the use of a Likert scale, respondents were asked to respond on a spectrum of “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” on such statements as:

I make it a priority to keep the Sabbath day holy, both in activity and in worship.

I live healthfully, which includes not eating or drinking harmful things.

In my household we prepare for the start of Sabbath on Friday evenings, both in thought and in activity.

With the data collected, I was able to stratify Adventist culture into roughly three divisions: high culture, medium culture, and low culture. Respondents who fell into the “high culture” category answered very positively in survey questions that

dealt with Adventist culture.

My findings indicated a correlation between the three distinctions of Adventist culture and school choice. Respondents who scored low in Adventist culture tended to put their children in non-Adventist schools. Adventists “in the middle of the road” more often opted to put their children in Adventist schools. Those who had high Adventist culture scores had a greater likelihood of choosing to homeschool their children.

There are profound implications from these empirical results. It could be posited that the sociopolitical climate in North America today has given way to much polarization. The gap between conservative and liberal political parties, for example, appears to only be widening; those on the left are even more staunchly in that camp, while those on the right seem to be firmly entrenched there as well.

I’ve traveled across the country for my work with the Center for Research on K-12 Adventist Education, and my perception is that this polarization is mirrored in the religious landscape, including our own Seventh-day Adventist faith community. Churches abound that speak out strongly against women’s ordination and alternative lifestyles, in much the same way churches that meet in warehouses and serve coffee at the bar before services are thriving.

Without turning this into a political discussion, I suggest that Seventh-day Adventist church members are indeed leaning more into either side today—more intentionally, more vocally, and more adamantly—than they were 50 years ago. Our schools, therefore, are too Adventist for those in the “low culture” bracket and not Adventist enough for those in the “high culture” bracket.

Furthermore, as members position themselves more strongly with the right or left, the population in the middle inevitably shrinks. And if—as results from this study show—church members in that middle window are the ones who consistently choose Adventist education for their children, then it certainly provides one explanation for why enrollment in our schools has shrunk over the past couple decades.

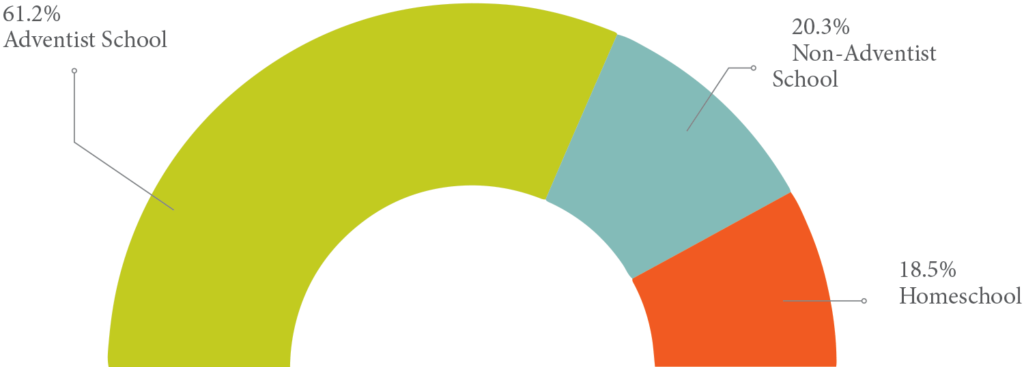

School Choice and Community.A large part of the Adventist culture is the community to which we belong. We are indeed card-carrying members of a people separated from one another by just two or three degrees. We all have heard stories or have our own personal anecdotes of visiting a new church and realizing that you attended academy with the pastor’s spouse or finding out that your son’s third-grade teacher was your own former junior high student. The Adventist Church is made up of a tight-knit community. And this study indicates that those social ties are strongly correlated to school choice.

Figure 2 shows that if parents attended a K-12 Adventist school for at least some of their educational experience, they are almost three times as likely to enroll their child in an Adventist school as they are a non-Adventist school. There is clearly a connection of history and legacy here; memories of academy banquets and music tours and vespers seem to linger at least long enough so that one generation desires to pass it down to the next generation.

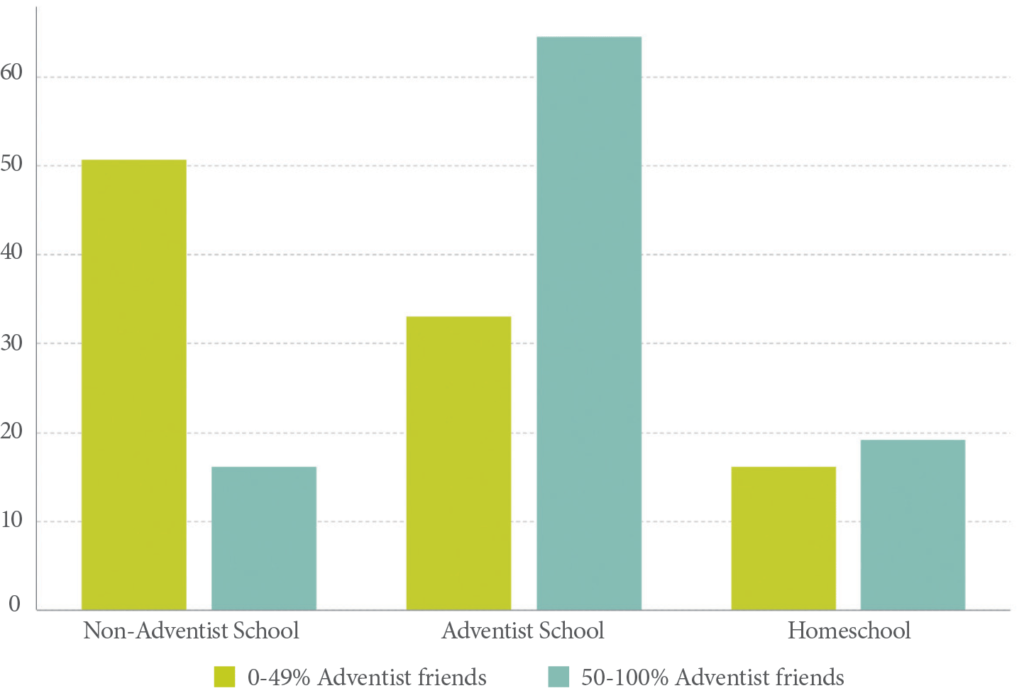

Another finding that speaks to the strength of community context was derived from a question about social network: “What percentage of your friends are Adventist?”

Looking at Figure 3, one can clearly see the ramifications of community on school choice. If parents are surrounded by like-minded people, if 50 to 100 percent of their friends are Adventist, they are twice as likely to choose an Adventist education for their children. Conversely, those whose social circles are made up of fewer Adventist friends have a greater likelihood of choosing non-Adventist schools for their children.

Common sentiment has been that enrollment numbers are tightly linked to the school itself—its offerings, its standards, its quality. If Adventist parents aren’t choosing Adventist schools for their children, there must be something wrong with the school, which, by extension, means that the solution can be found only in creating a fix for the school system.

The original premise for this study, though, was that trends in enrollment are not solely, or even largely, tied to the pros and cons of a single educational institution, but rather that these patterns could also be attributed to those who do the choosing—parents. Moreover, parents’ decisions are possibly complicated by a host of internal factors, including their own educational context and demographics, as well as the religious and cultural norms that they espouse based on the strength of their identity with the church.

The results of this study, therefore, pose interesting questions for church and school leaders. What is at the heart of Adventist education? For that matter, what is at the core of the Adventist Church? How much is our culture tied into doctrine and matters of salvation? Are these cultural norms that we know so well an integral, necessary part of our community, or do they instead act as an insular wall and unnecessarily separate those who speak the jargon and know the unspoken rules from those who don’t?

Should we, as a school system, perhaps take a more inclusive approach to education with the hopes of drawing in those from the “low culture” sector and appeal more broadly to the general public? Or should we even more strongly champion the cultural norms that have persevered from the days of our grandparents and great-grandparents and keep us intact as a community?

By holding Adventist culture up to an objective, concrete measure, this study managed to connect dots that had previously been held together by only anecdotal threads. It provides empirical evidence to suggest that not only is Adventist culture a real and tangible thing—it is also something that has an incredibly significant impact on the choices we make and the lifestyle we lead.

Leaders of our church should be encouraged to consider the ramifications of culture on the direction, mission, and goals of Adventist education for the future.

Aimee Leukert is a professor of education at La Sierra University.