At the close of the nineteenth century, Sunday laws experienced something of a revival in America. Beginning in 1864, a lobbying group known as the National Reform Association began in earnest to petition Washington to entrench America’s status as a Christian nation in the U.S. Constitution. When its campaign went nowhere, the group turned its attention to various Sunday laws at the state level—or “blue” laws,1 as they were often called—encouraging renewed adherence to those laws, since most states had not enforced them in many decades.

The idea of legally prohibiting labor on the first day of the week certainly wasn’t new; it had ironically followed some of the early colonists across the Atlantic, who were emigrating to free themselves from state interference with their personal faith. Upon their arrival, a number of prominent communities promptly enforced Sunday observance by law.

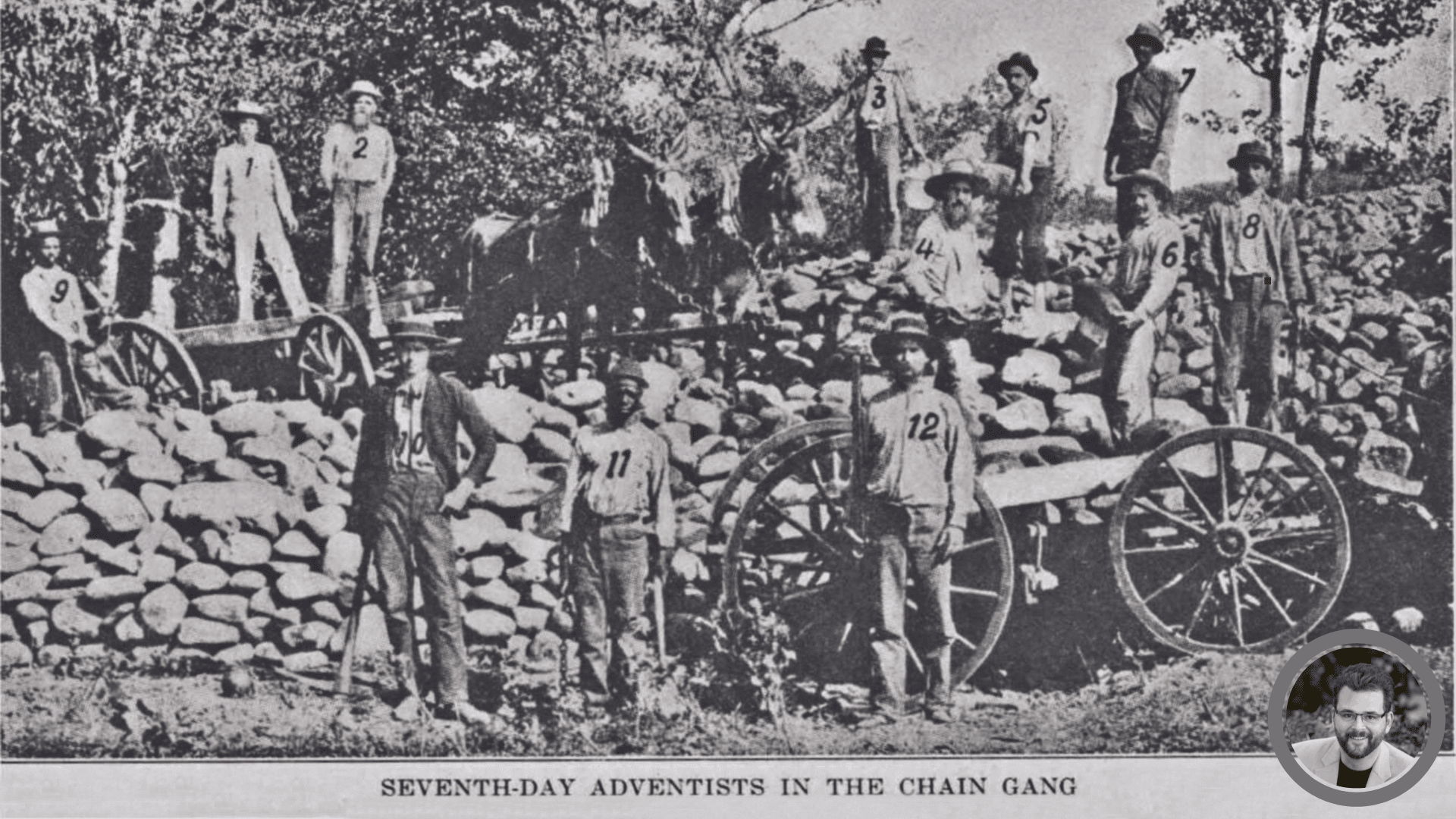

This second state-level attempt by the National Reform Association paid off, and before long it spelled trouble for a number of Seventh-day Adventists, who found themselves being prosecuted for the “crime” of laboring on Sunday. Willie White himself was arrested in 1882 for operating Pacific Press (then in Oakland) on the first day of the week. In other states—most notably Tennessee—Adventists were sentenced to serve on chain gangs for following their conscience.

The church’s warning against Sunday laws was not born out of paranoid fantasy: it was a present reality for many members. According to a statement in the American Sentinel of September 5, 1895, “In both Henry and Rhea counties, Tennessee, the chain-gang had fallen into disuse because it was found to be unprofitable, and it was revived specially for the punishment of Seventh-day Adventists. This is indicative of the temper of the Tennessee authorities.”

Our understanding of prophecy reveals that these sorts of laws, and the religious persecution that accompanied them, were just a warm-up act; we will see them again.2

Given the deeply emotional struggles our pioneers faced, and our understandable wariness of church-state complications, it isn’t surprising that the specter of yesteryear’s chain gangs made an appearance on the floor of the Session in St. Louis Wednesday morning, June 8. The assembled delegates were considering an amendment to the bylaws designed to enable the General Conference Executive Committee to remove members “for cause.” The amendment reads:

The phrase “for cause” when used in connection with removal from an elected or appointed position, or from employment, shall include but not be limited to 1) incompetence; 2) persistent failure to cooperate with duly constituted authority in substantive matters and with relevant employment and denominational policies; 3) actions which may be the subject of discipline under the Seventh-day Adventist Church Manual; 4) failure to maintain regular standing as a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church; 5) theft or embezzlement; or 6) conviction of or guilty plea for a crime.

The proposed amendment passed with a 90-percent majority, but not before it raised a few eyebrows—including mine. Do we really want the civil authorities deciding who is serving on our Executive Committee? I suddenly found myself paying attention, eager to understand what was being recommended.

In reality, the proposal didn’t suggest anything that isn’t already the practice of the church. “The words ‘theft or embezzlement’ have been incorporated into the model constitutions and bylaws and are also in the reasons for discipline of ministers,” general counsel Karnik Doukmetzian said to the assembly when debate over the motion started. “They have been in working policy for a number of years now. This is not something new; we are simply adding this to the General Conference Constitution.”

The strong support for the motion suggested it was not an issue for most people, but it was pointed out from the floor that Christians, including Jesus Himself, have been convicted of crimes of conscience since the beginning of the church. And it’s true: Paul was sentenced to death by the government, and so was Peter. Countless Christian martyrs have been tightly lashed to a stake after being labeled a criminal. What constitutes a “crime” can vary dramatically from place to place, or as history progresses.

Would this amendment require the Executive Committee to remove members who had committed “crimes” of conscience?

There is also the issue of crimes committed in other countries that would not be considered a crime in the United States. Another culture might deem the behavior of one of our church members to be criminal, while we would think nothing of it here. Would this amendment mean we would be bound to remove such people?

Then there is the matter of criminalized speech, an unfortunate reality for many of our brothers and sisters around the world, whose right to free speech is not guaranteed. And here in the West, many are getting the distinct impression that criminalized opinions and speech may land on our doorstep in the very near future. If that happened, as prophecy suggests it eventually will, would that mean nearly every Adventist would be prohibited from sitting on the Executive Committee?

The answer to all of these questions is no. The amendment doesn’t bind the church to respond to every criminal conviction indiscriminately, regardless of the nature of the member’s crime. The committee has discretion; a two-thirds majority vote (of 345 members) is required to invoke the amendment and remove someone. It seems highly unlikely that we would remove a member for having broken their own nation’s blue laws, or some other legal restriction on the free exercise of religion. Honestly, it would seem more likely that someone who had been prosecuted over the fourth commandment would receive an ovation.

“Here’s the thing,” Doukmetzian explained, when I asked him to sit down with me and help me navigate the reasoning behind the amendment. “First of all, the Executive Committee has discretion on whether it moves on someone or not.”

In other words, they don’t have to do it, but they can if the need arises.

But if the amendment already reflects current practice throughout the church, why do we need it? It’s because there hasn’t been a mechanism in place that enables the GC Executive Committee to remove members in the event that their employer—or the body who appointed them—has failed to deal with their criminal conviction.

“What changed was, it can now apply to the Executive Committee,” Doukmetzian elaborated. “It always applied to elected and appointed individuals. That was the problem. From an employment side, General Conference HR and the various committees can deal with everybody except those who are appointed and elected, because only that group that elected or appointed them can deal with their employment, termination, removal from office . . . whatever it happens to be. The provision—because it does say ‘elected or appointed’—could be taken to apply to members of the Executive Committee as well. But we wanted to be clear on that—that specifically, it does apply to members of the Executive Committee.”

If other levels of church governance fail to deal with a problematic individual, the GC Executive Committee would have been essentially powerless to deal with it. This amendment grants the committee the ability to police itself.

Would this mean that the General Conference Executive Committee doesn’t trust the other levels of church government? When a delegate asked that question, chair Ella Simmons responded, “It is so very important that we operate within the church family from a logic of confidence. And yet we have to take a global view—a global perspective on everything we do. And while most of us would be faithful and reliable just as you have described, it is unfortunate that there are possibilities and perhaps . . . there could be instances in which the church has come under scrutiny and challenge as a result of a person in a position to take action who did not.”

The church is, after all, made up of very fallible humans, and when faced with the unpleasant task of dealing with problematic individuals, some people occasionally flounder and choose not to deal with the turmoil and confrontational heartache that go along with it. Fortunately, it doesn’t happen often, but it does happen. So it certainly doesn’t hurt to have another level of accountability.

Caution, of course, is wise, especially given our history with (and anticipation of) the criminalization of our belief and practice. There is, however, another side to this coin that is equally important: Christian organizations have unfortunately earned a reputation for sweeping criminal behavior under the rug, hiding it from the public and pretending it never happened. How many stories have appeared in the headlines featuring denominations that ignored criminal abuse? With the ratification of this amendment, we have a degree of certainty that the Executive Committee doesn’t intend to be among those who turn a blind eye to such things.

Could a policy like this be abused or misapplied? Sure. That’s true of any working policy, which is why the decision hasn’t been left with a single individual. A substantial majority of the body that represents all of us must make the call, which makes it unlikely that it will be misused.

Could this create a problem for us with governments in the future? I’m not convinced, because it doesn’t bind the church to action over any and all perceived “crimes.” It’s not as if the state can swoop in and demand that we shut down operations and dismiss everybody because we’re holding a meeting on Sunday because they have declared us criminals. (I mean, sure, they could hypothetically do that, but not based on our policies.)

And when the scenarios predicted in the latter half of Revelation 13 finally come into play? It doesn’t seem likely that the GC Executive Committee would still be meeting at that point.

____________________________

1. Some believe they were termed “blue laws” because they were first printed on blue paper in the state of Connecticut, which is likely an urban legend, since not one copy on blue paper has ever been discovered.

2. Interestingly enough, there is something of a legal precedent for treating Sunday differently from other days of the week buried in Article I, Section 17 of the American Constitution, which gives the President “ten days (Sunday excepted)” to return a law to Congress.