I was plugging away at a routine task on Wednesday, the Adventist Review having graciously allowed me to crew on with them during the GC Session. Between sending copy to the editors and checking my email, I quickly logged into a social media account that I reserve for family and close friends only, and I noticed that it was my friend Preston’s birthday. For once, I thought, I caught someone’s birthday on the actual day, instead of shamefacedly offering belated well-wishes.

“Happy birthday!!!” I posted on his time line, using multiple exclamation points to underline my enthusiasm for his most recent trip around the sun. My good deed for the day completed, I returned to the unfinished tasks on the table in front of me, and moments later a message pinged from my inbox. It was a DM from another good friend.

“You know Preston passed away,” she said.

I did not. I sat stunned, staring at the message, hoping it was a mistake.

Preston and I went to school together at one time, and we had a lot in common. I always liked him. After I left for college we lost touch, until the advent of social media. At first, we had near-meaningless exchanges—niceties, mostly. And then one time he said, “It seems that you and I have taken different paths in life.”

That much was true—at least at that point. I had become a Christian and had entered the ministry. He was a biker whom the local police knew well. He resided on the edge of town in a trailer with his dog, and judging by the comments I heard from others, he was not well-loved in the community. Relationships inevitably fell apart on him. He lived in chronic pain.

When Preston lost his father, it was devastating for him. His dad had bought a motorcycle so he could connect more deeply with his son. Then on one of their first rides, Preston was looking in the rearview mirror and saw a vehicle crash into his father, who then died in his arms.

His mother was already dead. His relationship with his only brother was virtually nonexistent. He was alone in the world.

Reconnecting

One day I realized that a trip I was taking would bring me within a five-hour drive of Preston’s home, so I sent him a note. “Hey, Preston,” I said, “I’m coming to town. Can we meet? I’ll buy you lunch!”

He responded that he couldn’t meet me in town because his license was suspended: too many DUIs. So I suggested a rural gas station with a coffee shop on the highway near his trailer, and he agreed to meet with me. We sat across the table from each other, studying the decades etched on each other’s faces. He was obviously in pain and taking some sort of prescription opioids to manage it. He’d been beaten severely in prison by members of a gang, he told me, and now had to live with a crippled body as a result.

The food arrived. “I’m now in the habit of praying before a meal,” I told him. “I hope you don’t mind.”

“No,” he answered emphatically. “I sure don’t.”

I offered a simple prayer of thanks for the food, and then thanked God for the chance to catch up with an old friend. “Thank you for that,” he said, as a hint of a tear appeared in his eye and then quickly receded.

We ate. We talked. We reminisced about high school, and both of us agreed that we’d hated it. We laughed. We exchanged contact information, and we kept in touch. The conversations were fascinating. Preston was very intelligent and often challenged my thinking. I invited him to Colorado; he reminded me that his criminal record meant he wasn’t allowed to cross the border.

When he quit responding earlier this year, I assumed that—as he sometimes did—he’d pulled into his shell and pushed away the world for a bit. I understand that kind of thinking; I do it sometimes too. To misquote Ellen White’s statement on the X-ray, social media is not the great blessing some suppose it to be. For Preston, watching other people get on with life likely was painful.

Then in the middle of the GC Session, I found out that he was gone.

I’ve been around a lot of death throughout the years, and while it always bothers me, it doesn’t often rattle me. I’m fully aware that I’m also on the conveyer belt that will eventually drop me into a casket at the end, but Preston was in his early fifties. From the Christian perspective, death is never “natural,”but there’s something distinctly unnatural about deaths that happen off schedule: parents who bury children, or those who die from causes other than old age. From what I can gather, he died of a fentanyl overdose, that terrible scourge of the black-market drug trade. Had he done it on purpose? Unfortunately, I suspect he did. The pain—physical and emotional—had finally become too much.

Intellectually, I know there isn’t much I could have done to prevent Preston’s death, but the human heart doesn’t always follow the reasoning of the brain. I find myself wishing I’d tried harder; perhaps if I’d really emphasized that someone out there cared about whether he lived or died, he would still be here. That’s a game you really shouldn’t succumb to when these kinds of things happen, because it’s pointless.

But the thought of someone dying alone bothers me deeply. It shouldn’t happen to anybody. God forbid that I’m alone when the moment comes.

Oddly enough, on Tuesday I’d been talking about Preston with someone sitting near me in the Adventist Review Ministries workroom. Twenty-four hours later, I was in the same place staring at my computer screen in disbelief. He was gone.

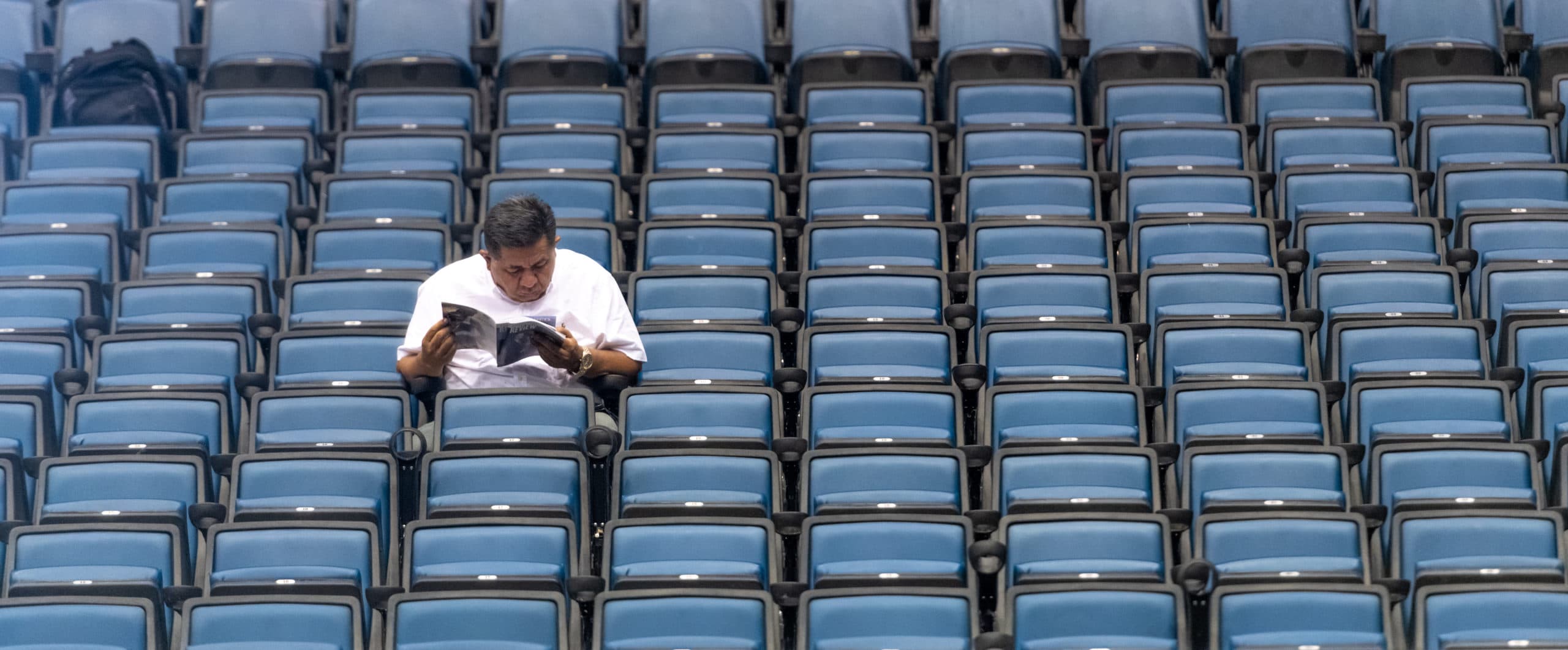

What our church does at Session is of vital importance; the work of a global church requiresthat we meet like this to fine-tune and retrofit the machine that makes mission effective. When you’re watching the proceedings courtside, it can look mundane and tedious. It’s easy for countless hours of policy minutiae to seem pointless. But Preston underlines why this is so important. The machine we tinker with is there to ensure that people don’t have to die meaningless, lonely deaths in a trailer on the edge of town. The world is a brutal place for most of us, but envision facing it without hope.

I’ve grown to understand why Jesus sometimes had to take a break from the press of the crowd. Imagine watching the brutality of human suffering from the perspective of the Creator, and you suddenly catch a glimpse of why the church is the object of His supreme regard.

Yes, we’re broken. Yes, like the disciples of old we continue to bicker. Yes, we can become self-absorbed and lose sight of the one and only thing Jesus has asked us to do: to seek and to save the lost. But still, we know that Christ prizes His church because it is that body of people who have heard the voice of Christ and who no longer believe that living is pointless.

* Name changed to protect identity.