The Sabbath of the crucifixion must have been one of the strangest days in history. The whole universe would have held its breath waiting for the next day, wondering if the promised resurrection was possible or whether God’s plan might have come to an unfortunate end.

The disciples, who apparently had little idea what was actually going on, were huddled together behind a locked door. The emotions they were all battling were incredible. The first emotion would probably have been heartbroken grief. Jesus had been their friend and their teacher. After a couple years traveling around the countryside with Him, their simple friendship would have been strong. Now He was dead.

The disciples also had dared to believe that Jesus was the Messiah for whom all the Jews had been waiting. Now that seemed to be all gone. Merely a week previously Jesus had moved toward what they thought would be the exercise of His Messiahship as He was acclaimed by the city of Jerusalem in the triumphal entry. Now He was dead after enduring great agony and shame. This was not quite the end they had expected for their Messiah.

The disciples were scared. They feared that, as Jesus’ closest supporters, they might be in danger of suffering a similar fate to that of their leader. The disciples had all been involved publicly in Jesus’ life and ministry and, to them, it would have appeared quite possible that the Jewish and Roman leaders would want to clean up the last of this prospective uprising by executing the closest of Jesus’ followers. 1

Somewhere in this wave of grief, doubt, and fear, somewhere in the back of the disciples’ minds, there may have been another emotion. With Jesus gone, the disciples would have no option but to return to the patterns of life and work they had been accustomed to before they threw in their lot with the Teacher from Galilee. That meant a cruel turn of the wheel, but at least it promised a future that was predictable and comfortable—and perhaps even relief-filled.

Jesus had had some strange ideas that the disciples had not properly understood and with which He often disturbed their thinking. He had often done things that did not make sense to the disciples. All that had come to an end now. Would they—should they—return to their normal lives?

There comes a point where Jesus must become alive and real to us.

If the disciples could just stay hidden for a few weeks, they could make their way carefully back to Galilee, and things could just go on as before. They might be ridiculed a little by some of their neighbors for wasting those few years, but this too would settle down in time. They could remember Jesus merely as a great friend and a short-lived hope that they had once held. In a few years they might even be able to share fond memories of their days with their traveling preacher friend.

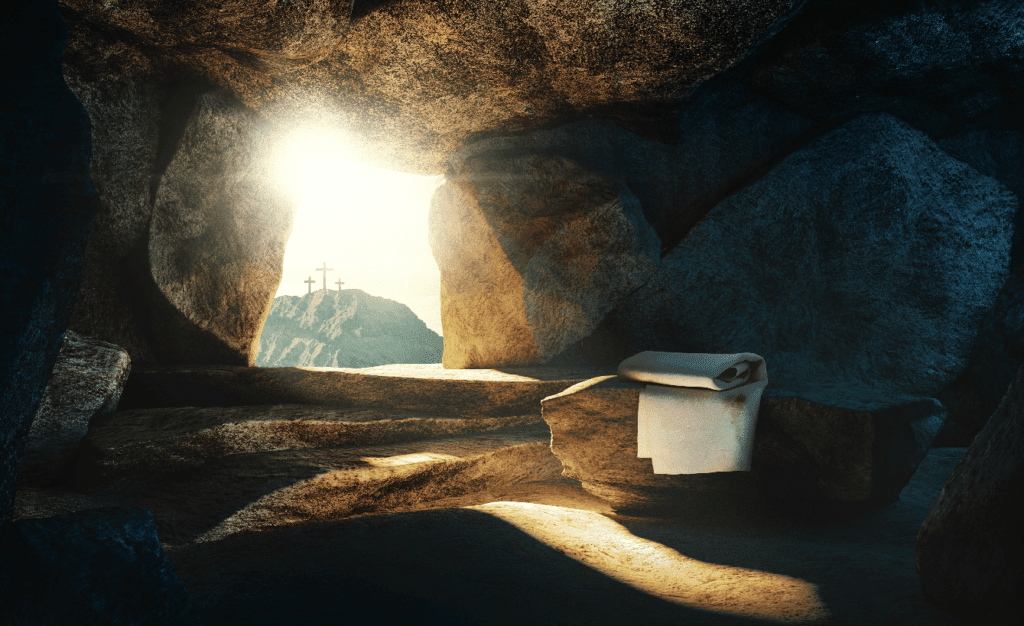

Their emotional maelstrom was intensified by the stories brought to them early on Sunday morning by the women who had been to visit Jesus’ grave. Later that day Jesus appeared to the two travelers on the road to Emmaus, and they shared their excited story with the confused disciples. And then, suddenly, Jesus was there among them—real and living.

On Sunday the disciples’ emotions underwent another radical shift. “The news of Christ’s resurrection was so different from what they had anticipated that they could not believe it.”2 All thoughts of a return to “normal” life were swept away. The two disciples, as they headed back home down the road to Emmaus, possibly to homes and jobs, were abruptly turned around— back to Jerusalem and back to the adventure of living and working for Christ as His followers—and a return to normal life was out of the question.3

The disciples must have struggled to come to terms with the reality of the resurrected Christ. For seven of the disciples, at Peter’s suggestion, there was even a brief return to the old days as fishermen, but again, Jesus interrupted their halfhearted attempts to return to normal life.4 Mingled with the joy that morning on the beach, Peter especially must have felt some trepidation in the wake of his denial just prior to the Crucifixion. Jesus took special care to allay Peter’s fears.

As they spent time with Jesus during the six weeks after the Resurrection, the disciples’ grief and fear evaporated—so did their “comfort zone.” The glorious certainty of the resurrected Messiah banished all thought of returning to normal life. Jesus worked with the disciples: He took time to explain His death and resurrection on the road to Emmaus; He diffused the specific doubts of Mary, Thomas, and Peter; and He answered many of the unspoken fears and questions that pressed upon the disciples.

Jesus had had some strange ideas that the disciples had not properly understood and with which He often disturbed their thinking.

In the wake of Jesus’ compassionate guidance, the disciples were left with no space to doubt and no other options—not even the tiny shred of “disappointment” they may have felt at first. Jesus now had even larger claims, and they had to do something about these claims. As Jesus talked with them, the disciples were compelled to believe, and their responsibilities were made plain. A return to “normalcy” was replaced with determination to change the entire world with the message of Jesus as the Christ. Instead of retreating from their shaky ideas and beliefs held prior to the Crucifixion, the disciples embraced these beliefs ever more fully and truly.

As Christians, “in a real sense we live on Saturday, the day with no name.”5 Living in a world in which God too often seems remote, it is easy to feel that God is of little consequence to our everyday lives. We can live with God a long way off, as if it is Easter Saturday. We may have known God, but He might not bother us anymore. At times we might feel some distress at our distance from God, but there is also some sense of relief.

Milan Kundera suggests that “the Christian believes in God in the full certainty that He will remain “invisible” and that there is a certain “kind of terror a Christian might feel on receiving a telephone call from God, announcing that He was coming over for dinner.”6 As humans, we think we are most happy when we are left to ourselves. Except in our most desperate circumstances, a respectful distance between God and us is comforting.

The disciples must have struggled to come to terms with the reality of the resurrected Christ.

There comes a point where Jesus must become alive and real to us. This can be a process of working through the realities behind the claims Jesus made. This can be something akin to the disciples’ experience during the weeks after that remarkable Sunday. While we might be searching for hope, the hope Jesus presents to us does not necessarily fit within our expectations, and there may be some measure of disappointment.

However, when Jesus does become real to us, we are called to live differently. We are called to live beyond ourselves in the certainty of Jesus’ death, resurrection, and love for us. The reality of Christ’s resurrection in our lives must make a difference. “The disciples who lived through both days, Friday and Sunday, never doubted God again.”7 The change that was worked in the lives of the 11 disciples confirms the glorious truth of the resurrection. It is such a change that must be effected in our lives.

In the wake of Jesus’ compassionate guidance, the disciples were left with no space to doubt and no other options.

As one writer put it: “True Christianity calls us to live on a cold and windy mountaintop, not on the flattened plain of reasonable, middle-of- the-road religion.” The only way in which the “challenge” of the resurrection of Christ can change us is to view it in the light of God’s great love. We must cling to that which causes the most discomfort to us as sinful people. We will then find Christ’s resurrection to be the source of ultimate comfort and hope and will be able to truly rejoice in the triumph of the Resurrection on that Sunday morning.

This article was first published on April 20, 2000, in the Adventist Review. At the time of writing, Nathan Brown was living in Queensland, Australia. He is now an editor at SIGNS publishing in Warburton, Victoria, Australia.

1 John 20:19

2 Ellen G. White, The Desire of Ages, p. 793.

3 Luke 24:13-35.

4 John 21.

5 Philip Yancey, The Jesus I Never Knew (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1995), p. 275.

6 Milan Kundera, The Farewell Party (London: Penguin Books, 1976), p. 113.

7 Yancey, p. 274.