Every picture tells a story. Every picture also has a story. Like this one.

It was 1973. I was 18 years old. Having graduated Miami Beach Senior High that spring (and having missed the draft, too), I tramped through Europe for the summer and returned to start at Miami-Dade Community College. I then bought a camera, a Minolta SRT-101, which became an appendage. I had turned my bedroom into a darkroom (made a hole in the window screen to get water from the outside faucet), and for two years my fingers were tinged brownish-yellow from Dektol, a chemical for developing Tri-X film. I probably reeked of it, too.

I also got a job at the Miami Herald. “Copy Boy” was the formal title; it captured the work, perfectly. Besides piddling office stuff, copy boys (and girls) would at times have to do a “run” in the office car, often picking up film from wherever. They once sent me to ask for a photo of a six-year-old girl just murdered. At the front door of her house, when I said, “Miami Herald,” they told me to get lost.

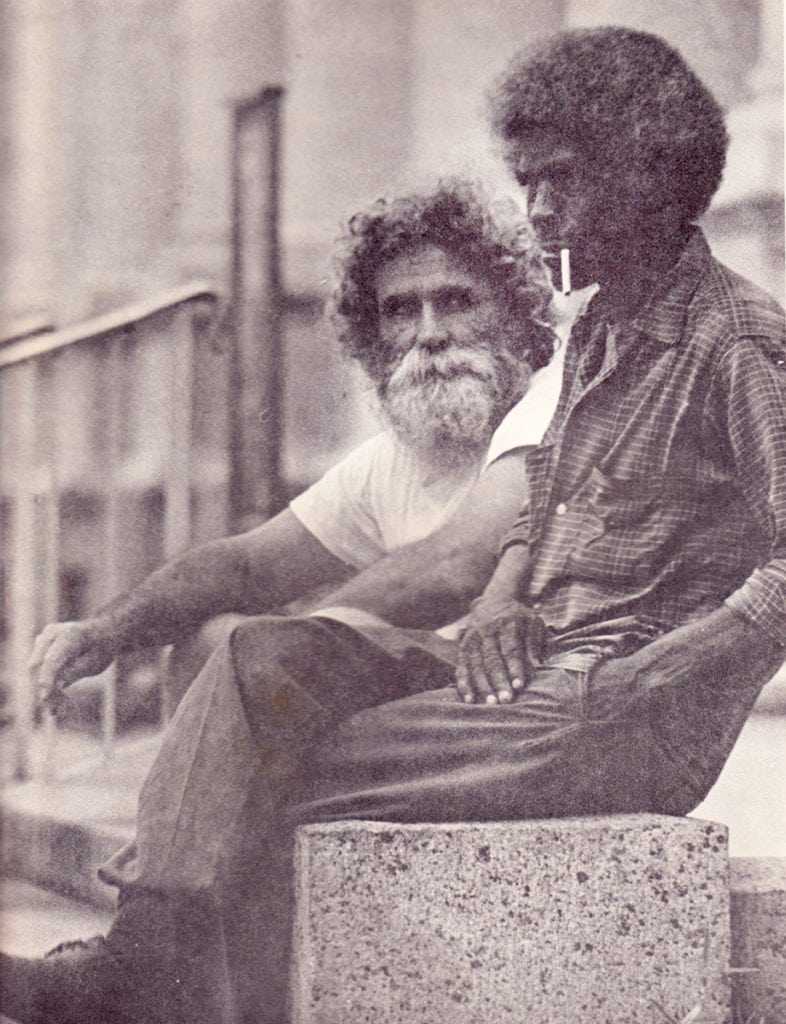

One time, on my way back to the office from a “run” to the bus station in downtown Miami, I saw the men in this photo from a distance. I pulled over, got out, set the camera on the car roof and, using a telephoto lens, snapped two shots, got back in, and forgot about them.

A few days later, in the darkroom, the two negatives came to chemical life, with the composition of one so catching my attention that I printed it. The photo turned out to be probably the best that I had ever taken. Three years later, broke, I sold my cameras and that was that.

Somehow, I don’t know how, or remember how—sitting in Dropbox, in a folder named oldgoldsteinphotos, in a subfolder called Cliff—this long-forgotten picture rematerialized, with “Scan 27.jpeg” as its filename. It instantly brought back the memory, clouded over by half a century, of this lucky shot.

And lucky it was. I didn’t see the first man’s eyes glaring fiercely, intently, as his hand reached in his pocket for (I’m sure) matches. Nor did I see his bearded companion’s sidelong glance. And I didn’t think about how the background would be blurred, making the two figures stand out so dramatically, even gracefully. A second or two later, it would have been another photo completely.

I wonder about these two men, whose humanity, or at least a split second of their humanity, plays out before you. What were they doing there, in this rough part of town dappled with homeless who usually funneled through the bus station before fanning out to hunt and gather in downtown Miami? They’re surely by now dead, flesh decomposed, existences and essences forgotten, even though those massive stone columns behind them are (I would imagine) still standing.

Though this one instant and this one splash of space have been captured together—how many more instants and splashes would have vanished into eternal nothingness but for one slight detail: the existence of Yahweh, whose omniscience and transcendence means that nothing, like these men, is ever forgotten. God retains it all.

Secular writers bemoan an existence, like ours, that always ends in oblivion, which makes an existence, like ours, meaningless. They would be right, but for that same detail again: Yahweh—who not only remembers everyone, like these two, but who, in the person of Christ, poured out His blood on the cross for them, having longed for their souls then as much as He longs for ours now.

This photo, of an instant long gone, should remind us that nothing is long gone, not before God, who knows it all, who remembers it all, and who will one day “bring to light the hidden things of darkness” (1 Corinthians 4:5) and who, through Jesus, will forgive us what we all so desperately need forgiven.

Who were these men whom “Scan 27.jpeg” exhumed from the past? What happened to them? What will happen to them (see Acts 24:15)? I don’t know. But I know that Yahweh does.

Clifford Goldstein is editor of the Adult Bible Study Guide.