BY BILL KNOTT

T LEAST ONCE IN EVERY SUMMER IT HAPPENS--a moment when a crystalline blue sky, hot sun, hotter sand, and the fragrance of pitch pines meld into an irresistible sensory overload.

T LEAST ONCE IN EVERY SUMMER IT HAPPENS--a moment when a crystalline blue sky, hot sun, hotter sand, and the fragrance of pitch pines meld into an irresistible sensory overload.

And I am back at camp again--lying beneath the draped mosquito netting under the tent flaps, wondering if the gneyh-gneyh-gneyh bugs in the treetops will stop singing before I fall asleep. Through the Texas thicket I can hear the sounds of other campers fussing, fighting naptime, teasing their counselors, urgent to be up and out and about on a day so blue, so hot, so pungent in the nostrils . . .

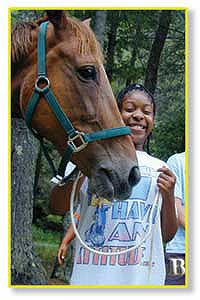

This is the way camp stories almost always begin--a highly personal recollection of earth and wind and water and sky in which somehow, perhaps for the first time, we are the actors. We are the ones--not our parents, not even our peers--smelling the deep earthfreshness of the pines, pulling the canoe paddle in the newly mastered "J" stroke, shambling along a dusty path in a line of old and gentle horses. And for a completely memorable moment, it is our identities that matter, our perceptions of the world that count, our hands getting blistered by the paddle.

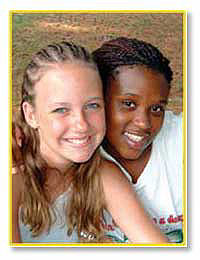

In a world muchly ordered by adults, such moments of awareness are both rare and unforgettable. The 10-month round of school and music lessons, predictable bedtimes, and routinized meals evaporates--dissolves-under the life overload of a week or two at camp. We make friendships in hours and lose them in minutes; try vegeburgers for the first time and witness tearful baptisms; hold snakes about our necks and hold our noses when assigned to clean out the horse stables; swallow lake water at prodigious rates and huddle under blankets as the night wind whips across the campfire bowl. At camp we are, uniquely, persons in our own right, not pale imitations of Mom or Dad, and nothing like those lazy louts in the Maple Cabin. At camp we see, smell, hear, taste, touch our world as only satisfied children can.

In a world muchly ordered by adults, such moments of awareness are both rare and unforgettable. The 10-month round of school and music lessons, predictable bedtimes, and routinized meals evaporates--dissolves-under the life overload of a week or two at camp. We make friendships in hours and lose them in minutes; try vegeburgers for the first time and witness tearful baptisms; hold snakes about our necks and hold our noses when assigned to clean out the horse stables; swallow lake water at prodigious rates and huddle under blankets as the night wind whips across the campfire bowl. At camp we are, uniquely, persons in our own right, not pale imitations of Mom or Dad, and nothing like those lazy louts in the Maple Cabin. At camp we see, smell, hear, taste, touch our world as only satisfied children can.

Summer camp. Ugottaluvit.

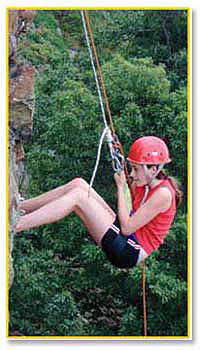

For more than 60,000 Adventist kids and their friends each year, the summer camps operated by the church across North America hold happy and even gracious associations. At more than 60 sites in the U.S. and Canada, kids 6-18 swim, bike, hike, water-ski, race go-carts, go rock-climbing, and study animal tracks in a sun-splashed haze where winning and losing, getting and gaining, are briefly rejoiced in and easily forgotten.

"It was the sense of liking my world that I gained at camp," says one middle-aged pastor who both attended summer camps as a child and worked at them as a teenager. "While the rest of my life often seemed fragmented, summer camp was truly an integrative experience. I want to make sure my kids don't miss that."

Indeed, it is the goal of just such "integrative experience" that causes the denomination to invest millions of dollars annually in its summer camp ministry across North America. Providing Adventist kids and their friends with fun, faith-filled experiences in the natural world has been a priority for the church's leadership since the era when Ellen White more than a century ago urged a more natural, outdoor lifestyle for believers: making that happen on a scale that meets today's much higher expectations for safety, recreational options, and staffing means that the quiet summer camps of yore are now truly "big business" for the church.

The commitment to summer camp ministry for its youth is estimated to be the second largest dollar amount expended each year on the church's youth, following only the sum committed to its large year-round K-12 educational system. Though no aggregate figures exist for the North American Division, sampling suggests that many midsize and large conferences are spending an average of $50-$60 per baptized member each year on their conference camps and centers, of which summer youth camps, ranging from two to 15 weeks a year, get the lion's share.

Many Moons Ago

Early Adventist summer camps were frequently small-scale and locally funded. As the Boy Scout/Girl Scout phenomenon swept North America in the early years of the twentieth century, local church youth leaders and concerned parents planned similar camping and outdoors experiences for Adventist kids at area parks or rural property made available by friends or church members. In 1926 the first conference youth camp was held in Townline Lake, Michigan--but for boys only. Three years later, in 1929, the granddaddy of Adventist summer camps--Camp Wawona in Central California--began operation.1

When the church's Pathfinder program emerged in the 1940s, the year-round operation of both congregational and conference Pathfinder structures spurred the acquisition of properties to host the fairs, camporees, and camping adventures. Many of the camps across the division began with property purchases in the 1940s and 50s; almost all have acquired significantly more property since then as both church leaders and lay members have embraced the vision of a vibrant youth ministry that extends well beyond Pathfindering.

When the church's Pathfinder program emerged in the 1940s, the year-round operation of both congregational and conference Pathfinder structures spurred the acquisition of properties to host the fairs, camporees, and camping adventures. Many of the camps across the division began with property purchases in the 1940s and 50s; almost all have acquired significantly more property since then as both church leaders and lay members have embraced the vision of a vibrant youth ministry that extends well beyond Pathfindering.

Not to Be Traded For

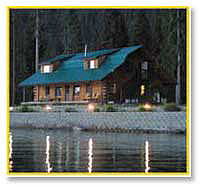

Today the denomination holds title to nearly 15,000 acres of rural and wilderness land across North America--or an area, if taken all together, about the size of the island of Manhattan. Several conferences (Florida, Michigan, Rocky Mountain, Alaska) have at least two locations. Camps range from the tiny (17 acres for Hawaii's Camp Waianae at the base of Mount Ka'ala on the island of Oahu) to the gigantic (Texas Conference's Nameless Valley Ranch boasts "nearly 1,000 acres").2 One camp-Wawona-is entirely inside Yosemite National Park; others, such as the Southern California Conference's Camp Cedar Falls and the New York Conference's Camp Cherokee, are located inside national forest territory. Some, such as Alaska's Camp Polaris, give a new depth to the definition of remote. The printed directions to the camp read, "Fly to Dillingham, drive to Aleknigik, and boat 12 miles up Lake Aleknigik."3

Despite the frequent association, not all summer camps are sited on lakes. Several border large rivers that can be used for boating, sailing, and skiing. Others have nearby road or trail access to manmade or natural bodies of water. One, Camp Pugwash in the Maritime Conference of Canada, boasts oceanfront property in the strait between Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Few Moccasin Prints

Most Adventist summer camps consciously seek to link campers to the land and to the heritage of Native Americans, whose cultures, traditions, and stories are frequently referenced in campfire programs and camp architecture. Nearly one fifth of Adventist camps have names that directly or indirectly evoke the Indian past. Almost all build on that heritage through the use of drama, outpost camps, building names, and special camper privileges. (Particularly "good"--that is, neat and on-time--cabins may get to spend a night in the large Sioux-looking tepee set up on one edge of the camp.)

Curiously, though, little effort has been expended in some places to make the evocation of the Native American past accurate or appropriate. Camp Cherokee, in New York's Adirondack Mountains, is nearly 1,000 miles away from the original homelands of the tribe whose name it bears. Southern New England's Camp Winnekeag (a name that requires repeated explanations for teetotaling Adventists) incongruously named its cabins Apache, Comanche, Dakota, Navajo, Winnebago, Cheyenne, Pawnee, Sioux, etc., while ignoring the names of the native tribes that once inhabited the very region in which the camp now operates (Massachuset, Abenaki, Mohegan, Pequot, Mohawk).

Curiously, though, little effort has been expended in some places to make the evocation of the Native American past accurate or appropriate. Camp Cherokee, in New York's Adirondack Mountains, is nearly 1,000 miles away from the original homelands of the tribe whose name it bears. Southern New England's Camp Winnekeag (a name that requires repeated explanations for teetotaling Adventists) incongruously named its cabins Apache, Comanche, Dakota, Navajo, Winnebago, Cheyenne, Pawnee, Sioux, etc., while ignoring the names of the native tribes that once inhabited the very region in which the camp now operates (Massachuset, Abenaki, Mohegan, Pequot, Mohawk).

Their Tribe Is Increasing

Those 60,000 Adventist kids and their friends who attend summer camps each year are served--and yes, that's the right word--by a battalion of high school and college-age Adventist youth who work as counselors, cafeteria helpers, teachers, water safety instructors, and maintenance personnel. More than 3,500 such youth served in the most recent year for which records are available, and almost all did so to earn scholarships for Adventist secondary and collegiate institutions. Through the decades a unique partnership has emerged between the denomination's educational and youth ministries that produces an estimated $9 million a year in school tuition and living expenses for teenagers and young adults employed at summer camps.

The summer camp experience of working with and for children is frequently intense and sometimes painful. Old images of simply "hanging out by the pool" as a summer camp employee have nearly vanished in an age when nearly half the kids arriving at camp are children of divorce or children who live in single-parent homes. Kids come to summer camp today with a wider range of personal and social issues than ever before: substance abuse and inter-ethnic rivalries are not all left behind in their urban or suburban streets. In addition to supplying the emotional support traditionally expected of a camp counselor--for loneliness, problems making friends, homesickness--employees must now be trained to spot situations of abuse and neglect and to alert camp authorities to situations that may require intervention.

The summer camp experience of working with and for children is frequently intense and sometimes painful. Old images of simply "hanging out by the pool" as a summer camp employee have nearly vanished in an age when nearly half the kids arriving at camp are children of divorce or children who live in single-parent homes. Kids come to summer camp today with a wider range of personal and social issues than ever before: substance abuse and inter-ethnic rivalries are not all left behind in their urban or suburban streets. In addition to supplying the emotional support traditionally expected of a camp counselor--for loneliness, problems making friends, homesickness--employees must now be trained to spot situations of abuse and neglect and to alert camp authorities to situations that may require intervention.

Many camp staff report very high satisfaction with their work, however, despite the challenges of 24/7 ministry to a spiritually and emotionally needy population. For many the experience of leading cabin devotions, participating in worship leadership, and hours of one-on-one conversation with children and fellow staff needing spiritual support elicits a desire to serve in a ministry as a life's work. Teachers, pastors, health-care workers, child-care professionals, counselors--all are formed in the crucible of summer camp ministry.

"If we didn't have summer camp ministry to help us see those whom God has gifted for special ministries, we'd have to invent it," says one church administrator. "It's one of the most important places where Adventist youth and young adults are proving and improving their skills to serve God's remnant church."

Best numbers from the North American Division Youth Department indicate that more than 20,000 children and youth make decisions for Christ each year during their time at camp. Nearly 40 percent of these--8,000 kids--go on to request baptism and church membership.4 Other than the ongoing ministry of the church's educational system, no other youth ministry of the church yields larger growth for the denomination than summer camp ministry.

Without Reservations

The organization now known as National Camps for Blind Children (a ministry of Christian Record Services) began sponsoring blind and visually impaired children of all religious backgrounds at Adventist camps in the summer of 1967. Tens of thousands have now attended one or more weeks at camp; thousands have accepted Christ as Savior, and many of these have found a spiritual home in the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

NCBC campers participate in the full range of summer camp programs, sometimes with the help of special equipment, but often with only the addition of pluck and courage lacking in their sighted companions. Waterskiing, archery, hiking, rock climbing-all are successfully accomplished through the tenacity of the campers and the patience of supportive camp staffs.

Children with multiple challenges, including hearing impairment and motor skill impairment, have also been welcomed at Adventist summer camps, some of which have made adaptations in equipment, programs, and accessibility to accommodate these special campers.

The Growing Village

The junior camps of the 1950s and '60s that served mainly 8- to 16-year-olds have been replaced by a wider range of camping choices across a greater span of ages. Children as young as 6 now attend camp "on their own;" older teens and young adults also have designated weeks in many conference summer camp schedules. Since the 1970s "family camps"--often less-structured, relaxing vacation weeks in which whole families stay together as a unit--have become increasingly popular.

Sports camps, featuring basketball and baseball, have appeared in several regions. Specialty camps for waterskiing, horsemanship, mountainbiking, and wilderness camping have become regular placeholders in the summer schedule.

Sports camps, featuring basketball and baseball, have appeared in several regions. Specialty camps for waterskiing, horsemanship, mountainbiking, and wilderness camping have become regular placeholders in the summer schedule.

The intensive summertime use of the camps has been augmented by an increasingly year-round calendar at many conference camps, especially those in temperate climates. Some of the larger camps literally operate every week of the year, hosting conventions, church retreats, youth leadership and prayer conferences, and school outdoor education adventures.

As overall use of camp facilities has escalated, conference financial investment has also increased. The latest statistics suggest that approximately one in three North American Seventh-day Adventists visited or stayed at a conference camp in 2001. Only worship services in 4,500 local congregations draw a larger number of Adventists from their homes in any given year.

The Memories of Our People

The gneyh-gneyh-gneyh bugs in the pin oak trees have long since stopped their singing. A late-afternoon breeze from up near Amarillo has swept over the camp, chilling the beginners practicing the crawl in the swimming area, blowing more than one novice sailor into the reedy end of the lake. The day has changed. The shadows grow.

A dozen evening tasks commence: tying up the wayward boats, stacking firewood in the campfire bowl, slicing watermelon for dessert, practicing the sturdy wagon train skit. Somewhere the camp pastor muses to himself, "What story shall I tell tonight?"

That all of this--this magical concentration of wind and water, earth and sky, people and programs, fun and faith--should be for us, the kids who live on Sycamore Street and Prairie Lane, seems too good, too wonderful, to be true. We will remember this day, we tell ourselves, as we spit the watermelon seeds among the uncaring catfish in the lake. No chance of forgetting this.

Summer camp. Ugottaluvit.

_________________________

1 "Your Guide to Adventist Christian Camps of North America" (brochure produced by the North American Division of the Seventh-day Adventist Church Camp Ministries and the Association of Adventist Camping Professionals), 2003.

2 North American Division Camp Ministries 2003 Membership Directory, p. 115.

3 Ibid., p. 80.

4 "Your Guide."

_________________________

Bill Knott is an associate editor of the Adventist Review.