HILE THE TEN commandments may certainly be viewed as a place to start living a moral existence—a jumping-off point, as described by Angela Ford Baerg on page 14—it is crucial that we do not underestimate the importance of this set of rules, nor the application of them as seen through the Light that illuminates from the New Testament. Ellen White was most specific as she harkens back to Scripture: “Commandment-keeping Adventists occupy a peculiar, exalted position. John viewed them in holy vision and thus described them: ‘Here are they that keep the commandments of God, and the faith of Jesus.’”

1

Not since Charlton Heston’s (Hollywood) Moses favored movie screens in 1956 had there been such fervor over the commandments. We can thank chief justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama Roy Moore (2001-2003) for its resurgence into popular culture. Little did Moore know that the act of hanging a wooden plaque of the commandments behind his courtroom bench, when his circuit judge tenure began, would ignite such controversy. In response to that act, and to Moore’s presession prayers, the American Civil Liberties Union of Alabama filed a lawsuit against Moore in 1995, claiming that the courtroom prayers and commandments display were both unconstitutional. In 1996 Circuit Judge Charles Price issued a ruling declaring the prayers unconstitutional and requiring the plaque to be removed. Moore appealed the decision and defied the ruling. The court never decided in the case, throwing it out for technical reasons in 1998.2

Bigger Is Better?

Centering his campaign on religious issues, Moore won the race for chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court in the fall of 2000. A month after his election, he began making plans for a larger monument of the Ten Commandments for the Alabama Supreme Court building’s central rotunda. He was sworn in on January 15, 2001.

On August 1, 2001, the monument was unveiled with Moore declaring, “Today a cry has gone out across our land for the acknowledgment of that God upon whom this nation and our laws were founded. . . . May this day mark the restoration of the moral foundation of law to our people and the return to the knowledge of God in our land.”3

On October 30, 2001, the ACLU of Alabama, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, and the Southern Poverty Law Center were among the groups that filed suit, asking that the monument be removed because it sent “a message to all who enter the State Judicial Building that the government encourages and endorses the practice of religion in general and Judeo-Christianity in particular.”4

Moore refused to comply, claiming that the commandments are the “moral foundation” of the U.S. law, and that in order to restore this foundation, “we must first recognize the source from which all morality springs.” He acknowledged that the monument “reflects the sovereignty of God over the affairs of men, and God’s overruling power over the affairs of men.”5

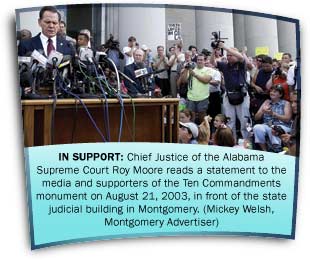

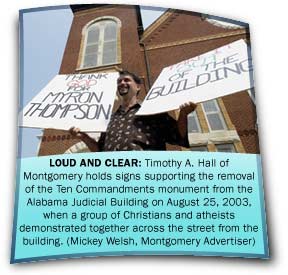

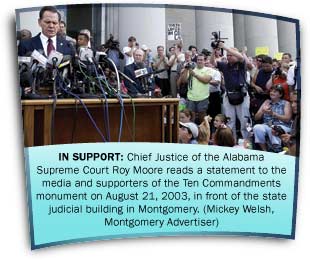

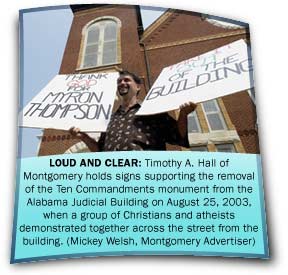

Large rallies (including one rally of about 4,000 on August 14, 2003) in support of Moore and the Ten Commandments monument formed in front of the judicial building. Speakers included Alan Keyes and Jerry Falwell. On August 21 the Alabama Supreme Court unanimously overruled Moore and ordered the monument removed. And while Moore was removed from his office on November 13, 2003, the monument wasn’t seized until July 19, 2004.

The controversy and attention surrounding the Decalogue didn’t end there. The Alabama case and others that followed from various states (including Texas and Kentucky) forced the issue to the Supreme Court of the United States, and on June 27, 2005, the high court ruled 5-4 in favor of barring exhibits in two Kentucky courthouses while allowing one exhibit at the Texas capital.6 With such a close ruling, the debate that ensued was fierce from both sides. “This is not time to deny the prudence of understanding the Establishment Clause [of the First Amendment] to require the government to stay neutral on religious belief, which is reserved for the conscience of the individual,” wrote Justice David Souter in the majority ruling read from the bench. Justice Antonin Scalia also read from the bench, but it was the dissent, which cited “the interest of the overwhelming majority of religious believers in being able to give God thanks and supplication as a people, and with respect to our national endeavors.”7

The Call Goes Out

The court’s split decision was the catalyst for the Ten Commandments Commission’s emergence in 2005. The TCC is the self-proclaimed “grass root movement whose objective is to have

5 million strong members/supporters and bring the Ten Commandments . . . message to every church and ministry in the nation. . . . The recent Supreme Court ruling regarding the removal of the Ten Commandments from public places gave us a golden opportunity to use this as a unifying cause among a vast number of conservative groups. . . . We maintain that those who care about traditional values cannot passively sit by and watch the removal of the very principles that made this country great. The Ten Commandments are the heart of all moral code and must be restored to the heart of our society.”8

The TCC announced it would promote a nationwide celebration of Ten Commandments Day on May 7, 2006, and went about gathering support from a variety of Judeo-Christian faith groups.

More interested in the court cases about public presentations of the Decalogue, the event was not covered by the major news entities: CNN, Time, MSNBC, etc. There was brief mention of the TCC in Newsweek and USA Today, and the Washington Post printed a feature article in the May 6, 2006, Saturday edition (“Groups Tout Ten Commandments Event,” by Michelle Boorstein, Section B, p. 5). In Boorstein’s article Ron Wexler, TCC founder and Orthodox Jew, explained that the observance of Ten Commandments Day would consist mostly of “a broadcast of speeches on dozens of radio and television stations.”9 The group also called for clergy at churches and synagogues nationwide to preach about the importance of the commandments.

The event was covered by news organs of the Adventist Church—Adventist News Network, Adventist Review, union magazines, and Web sites. And not only did our church give the day press time, Adventist groups and businesses put out their own news releases on how they were participating. Adventist entities joined in the celebration, participating quite heavily in 2006—but in their own way.

Doing It “Our” Way

The satellite TV station Three Angels Broadcasting Network gave away 270,000 copies of the book Ten Commandments Twice Removed on May 4, 2006, and held an event at the D.C. Armory featuring music and sermons about the commandments that aired in its satellite programming—after a blitz of Internet marketing, radio spots, and fliers. Amazing Facts and others partnered with 3ABN to produce broadcasts on May 5 and 6, encouraging viewers and church members to implement May 7 as a powerful witnessing opportunity “with their Christian friends to call them back to the true seventh-day Sabbath.”10 Amazing Facts also launched a new site, www.TenCommandmentFacts.com.

The Adventist Church’s Hope Channel brought special reports to its viewers on the Ten Commandments Day movement in the United States and created a special TV program that featured

Liberty magazine editor Lincoln Steed, evangelist and a vice president of the Adventist world church Mark Finley, and John Graz and Jonathan Gallagher of the Adventist Church’s Public Affairs and Religious Liberty Department. The panel discussed God’s gift of the Ten Commandments and the role they play in a Christian’s life.

11 In addition the Hope Channel aired a segment on “Written in the Heart”—a three-day event that featured special seminars, visits to congressional representatives by church members, and a religious liberty rally on Capitol Hill—as well as a question-and-answer segment with Brad Thorp and Gary Gibbs, president and vice president, respectively, of Hope Channel; and attorney James Standish, director of legislative affairs for the Adventist Church.

Three books were also released in 2006 to coincide with the event: Taking a Stand for the Ten Commandments, by Mark Finley, a booklet published by Pacific Press; The Ten Commandments Under Attack, by 12 prominent Adventist evangelists, developed by Signs of the Times and Pacific Press; and The Ten Commandments: What If We Did It God’s Way? by Loron Wade, published by the Review and Herald.

TCC is not without its political agendas, which is why some groups, including the Adventist Church, have treaded carefully, making the significant distinction that while supporting the Ten Commandments and their importance, they do not support the TCC. Some might even go so far as to wonder if the TCC, with its very prominent sales promotion of Ten Commandment pins, is merely trying to create awareness and support—or make money off commandment supporters.

So how do—or should—Adventists relate? According to the North American Religious Liberty Association and the Seventh-day Adventist Church State Council, “the work of the Ten Commandments Commission also extends to political issues that the Seventh-day Adventist Church does not support. The commission is protesting Supreme Court and lower court decisions regarding the display of the Commandments on Government property. They see these legal battles over the Ten Commandments as part of a war between Christians and secularists over the moral heritage of the nation. Seventh-day Adventists cannot conscientiously join in this culture war.

. . . Seventh-day Adventists have long championed the new covenant promise of God to write His law upon the human heart, and in the mind, . . . Adventists encourage all who seek to honor God’s law, and to turn attention to the importance of obedience to God. . . .We can support the work of the [TCC] in urging Americans to honor the Ten Commandments, and to recover its value for their own lives.”12

A New Day

That was last year. And while one cannot argue with the truth found in the above statement, there forms a question. This past May 6 was Ten Commandments Day. Where was the fervor from the past year? Sure, 3ABN presented a 17-hour marathon of specials and live broadcasts, and the TCC claimed that thousands of citizens celebrated the day (they signed the proclamation, at least). But there was nary a peep or squawk to be heard on the TV networks, in the papers, or in cyberspace. Why? Have the commandments become less marketable? Less en vogue? Less important? If Mollie Ziegler Hemingway’s editorial on “Houses of Worship: The Decline of the Sabbath”13 is any indication, many Americans (including Adventists?) toss the Sabbath commandment in favor of personal interests and pursuits. In society, have the other commandments really fared much better?

Perhaps it is wise not to tie ourselves to an organization we cannot fully support. Perhaps using the commandments as a moral compass relates to something inside us, rather than perched upon a wall or etched in a monument. And perhaps we should not focus all our soul-winning efforts on one day—or on one piece of the gospel pie. After all, the greatest commandment of all is: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind” (Matt. 22:37). Perhaps we should tout that. Anyone for that celebration?

______________________

1Testimonies for the Church, vol. 2, p. 450.

3Ibid.

4Ibid.

5Ibid.

7Ibid.

13From www.wsj.com, the OpinionJournal of The Wall Street Journal editorial page.

_______________________________________

Kimberly Luste Maran is an assistant editor of the Adventist Review.

HILE THE TEN commandments may certainly be viewed as a place to start living a moral existence—a jumping-off point, as described by Angela Ford Baerg on page 14—it is crucial that we do not underestimate the importance of this set of rules, nor the application of them as seen through the Light that illuminates from the New Testament. Ellen White was most specific as she harkens back to Scripture: “Commandment-keeping Adventists occupy a peculiar, exalted position. John viewed them in holy vision and thus described them: ‘Here are they that keep the commandments of God, and the faith of Jesus.’”1

HILE THE TEN commandments may certainly be viewed as a place to start living a moral existence—a jumping-off point, as described by Angela Ford Baerg on page 14—it is crucial that we do not underestimate the importance of this set of rules, nor the application of them as seen through the Light that illuminates from the New Testament. Ellen White was most specific as she harkens back to Scripture: “Commandment-keeping Adventists occupy a peculiar, exalted position. John viewed them in holy vision and thus described them: ‘Here are they that keep the commandments of God, and the faith of Jesus.’”1

Large rallies (including one rally of about 4,000 on August 14, 2003) in support of Moore and the Ten Commandments monument formed in front of the judicial building. Speakers included Alan Keyes and Jerry Falwell. On August 21 the Alabama Supreme Court unanimously overruled Moore and ordered the monument removed. And while Moore was removed from his office on November 13, 2003, the monument wasn’t seized until July 19, 2004.

Large rallies (including one rally of about 4,000 on August 14, 2003) in support of Moore and the Ten Commandments monument formed in front of the judicial building. Speakers included Alan Keyes and Jerry Falwell. On August 21 the Alabama Supreme Court unanimously overruled Moore and ordered the monument removed. And while Moore was removed from his office on November 13, 2003, the monument wasn’t seized until July 19, 2004. The Adventist Church’s Hope Channel brought special reports to its viewers on the Ten Commandments Day movement in the United States and created a special TV program that featured Liberty magazine editor Lincoln Steed, evangelist and a vice president of the Adventist world church Mark Finley, and John Graz and Jonathan Gallagher of the Adventist Church’s Public Affairs and Religious Liberty Department. The panel discussed God’s gift of the Ten Commandments and the role they play in a Christian’s life.11

The Adventist Church’s Hope Channel brought special reports to its viewers on the Ten Commandments Day movement in the United States and created a special TV program that featured Liberty magazine editor Lincoln Steed, evangelist and a vice president of the Adventist world church Mark Finley, and John Graz and Jonathan Gallagher of the Adventist Church’s Public Affairs and Religious Liberty Department. The panel discussed God’s gift of the Ten Commandments and the role they play in a Christian’s life.11