“In August 2005 members of the Huichol ethnic group belonging to the Seventh-day Adventist, Baptist, and Apostolic churches were driven from their homes in the community of Agua Fria, Mezquitic Municipality, Jalisco. Village leaders charged that evangelicals did not follow community bylaws, which require partaking in native religious practices, including the use of liquor and peyote. . . . According to press reports, at least 120 persons fled their homes and sought refuge in the neighboring state of Nayarit.”*

Y PACK WAS HEAVY. I WAS HOT AND thirsty. My tired feet tripped over the stones (beneath which, I knew, lodged scores of scorpions) that littered the path. Ahead of me 6-year-old Brenda trotted along lightly, carrying a fully-loaded Huichol woven bag from her forehead, a gallon jug of grayish drinking water in one hand, and a puppy in the other. No one in a Huichol village shirks work—even the children. We were climbing a mountain path to attend church in a new settlement for 30 Seventh-day Adventists who’d been driven from their ancestral home for having accepted Jesus Christ.

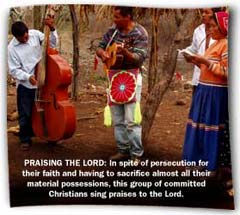

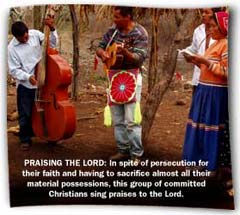

Except it wasn’t much of a settlement. At the crest of a hill six Huichol families live under tarps—old advertising banners Dagoberto Cirilo, an Adventist pastor and mission pilot, scavenged from the recent Mexican presidential election. As these families sleep, 20-foot faces of presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador look down on them. No houses, no fields, no food, no livestock, no school, and no church—only a clearing where we sat on stacks of flat stones to sing hymns and study the Bible.

The Huichol (pronounced hwee-CHOLE) are indigenous Mexicans whose ancestry goes back to the Aztec Empire. When Spanish colonists pushed into central Mexico in the sixteenth century, some of the native people assimilated and converted to Catholicism; a few, though, resisted the new culture and fled into the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains north of Guadalajara, where they adapted to life in the cool high desert. Until relatively recent times, most Huichol didn’t even speak Spanish, but a language descended from ancient Aztec. Because they resist evangelism and Western culture, they’ve changed little. They are animists (nature worshippers), whose central deities are corn, the deer, the peyote cactus, and the eagle, with occasional threads of distorted Catholicism tangled in. Like a few other Native American groups, the Huichol eat hallucinogenic peyote cactus in an attempt to establish mystical contact with their gods. They’ve intrigued the outside world not only for their untouched culture (they’re a favorite of anthropologists) but also for their colorful clothing and craftwork.

But in recent years Protestant Christianity has entered the Sierra Huichol, and with it conflict.

Seventh-day Adventists have been reaching out to the Huichol for more than 50 years. Because Huichol territory is so remote, they can be reached only by air. The heart of the Adventist Church’s ministry to them is the Huichol Flying Clinic, a Cessna 206 with which Pastor Cirilo delivers medical and spiritual care, and takes to the hospital those who are seriously ill.

Seventh-day Adventists have been reaching out to the Huichol for more than 50 years. Because Huichol territory is so remote, they can be reached only by air. The heart of the Adventist Church’s ministry to them is the Huichol Flying Clinic, a Cessna 206 with which Pastor Cirilo delivers medical and spiritual care, and takes to the hospital those who are seriously ill.

While the Huichol accept care from the church, most have not accepted Christ. In the tiny village of Agua Fria a few families were baptized, and though not allowed to build a church, they met quietly in homes.

Their neighbors began to notice a change—and some didn’t like it.

In 2002 the Huichol tribal elders called Adventist church members to a meeting. “You refuse to take peyote and drink the tejuino corn beer,” the elders said. “Do you belong to a different religion?” (The Huichol word for religion is “custom,” implying that to them, joining a new religion was equivalent to ceasing to be Huichol.) The Adventist believers admitted they had become Christians. Then, the elders said, they were no longer of the Huichol tribe.

Because the Huichol consider all land owned by the tribe, the Christians were to leave their ranchos by June 2003. (Other Protestant villagers were being similarly harassed; Roman Catholicism has to some extent synchronized into the native religion, but by refusing to participate in tribal customs the Protestants upset the social order.)

On Sabbath, June 7, 2003, the Huichol leaders again called the Christians before them. By now, Baptist and Apostolic believers were also targeted. The leaders demanded the Christians publicly denounce their beliefs, and prove it by taking peyote and drinking tejuino.

Cirilo, realizing the crisis his congregation faced, had flown in for the meeting, and he now asked permission to address the tribal elders. He explained their threats were illegal because the Mexican government protects freedom of religion. The believers were not uncooperative with the tribe, he said; they wanted only to be excused from using hallucinogens and intoxicants. His words only made them angrier. “Are you willing to die for your faith?” one asked Cirilo threateningly.

“Unquestionably,” Cirilo replied.

“Who gave you permission to come here in the first place?” another challenged.

“There are at least five people here tonight whose lives have been saved because our flying clinic has been here,” he countered.

The leaders began speaking in Huichol so Cirilo couldn’t understand them. If any Huichol tried to translate, the elders taunted them: “You really don’t belong here if you won’t even speak your own language!” After conferring, the elders ordered the Flying Clinic to leave the area and not return.

“Thank you for the chance to serve you for 11 years,” Cirilo said. “And if you ever have an emergency, just send word, and I’ll come.”

When Cirilo reported these events to the Mexican authorities, they temporarily halted the tribe’s proceedings against the Christians. But threats continued. Cirilo was falsely accused of destroying Huichol shrines. Others tried to create trouble for the Christians by planting marijuana, a common but illegal crop, on their land. Some Christians found valuable livestock killed. School authorities discriminated against Christian students, and tribal authorities refused them government benefits and food.

When Cirilo reported these events to the Mexican authorities, they temporarily halted the tribe’s proceedings against the Christians. But threats continued. Cirilo was falsely accused of destroying Huichol shrines. Others tried to create trouble for the Christians by planting marijuana, a common but illegal crop, on their land. Some Christians found valuable livestock killed. School authorities discriminated against Christian students, and tribal authorities refused them government benefits and food.

Then in February 2004, the threats turned to violence: Adventist member Hermelinda Vasquez’s home was burned by an angry villager. The roof collapsed on her, causing horrible burns over much of her body.

Again Huichol authorities called a meeting. They told the Christians they would have to leave by August 20, 2005. The accusers publicly jeered at them.

“What Dagoberto Cirilo has taught you about the resurrection when Christ returns is untrue, for we Huichol know that death is the end!” one shouted.

The Mexican government was of little help; representatives of Mexico’s National Commission for Human Rights listened impassively. The attorney general for the Bureau of Indian Affairs commented unhelpfully that if the Christians would just agree to follow Huichol traditions with regard to peyote and tejuino, everything would be quickly settled.

With only a few days before the deadline, Cirilo sadly told his parishioners that the risk to their lives had become too great, and it would be best for them to leave. The village elders allowed each family two bags of clothes, bedding and cooking utensils, plus a corn mill. They left behind land, houses, crops, fences, and fruit trees—the labors of a lifetime.

The Adventist families spent several weeks camping behind an Apostolic church, and several more at an Adventist camp meeting grounds. But they needed a place of their own.

In mid-2006 (through the mediation of Cirilo) another Huichol community, one more accepting of Western ways, granted them a small, undeveloped tract on the edge of the Aguas Milpas hydroelectric reservoir in the state of Nayarit. Other Huichol Christians have also been relocated to this area.

People who’d spent their entire lives in a desert now can leave their village only by a motorboat ride. Though far from their home in the Sierra Madre, the Adventist believers named their new village Agua Fria, in memory of the place from which they were driven. These 30 Adventists are the remnant believers who stood for their faith in the face of persecution.

As I worshipped with the Huichol Adventist believers, I reflected on the temporariness of human homes. The people of Agua Fria have left everything to follow Jesus. One of the hymns in worship that day was the old Spanish favorite “Más Allá Del Sol”—“Far beyond the sun, up there is my home, my home, blessed home, far beyond the sun.”

Never has the promise of that hymn seemed more meaningful, or more precious!

_________________

*From the U.S. Department of State Web site: Mexico: International Religious Freedom Report 200 (www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2006/71467.htm).

______________________________________

Loren Seibold is pastor of the Worthington, Ohio, Seventh-day Adventist Church. He has been working on behalf of the Huichol people for almost 20 years, and is a member of the executive board of Amistad International.

Seventh-day Adventists have been reaching out to the Huichol for more than 50 years. Because Huichol territory is so remote, they can be reached only by air. The heart of the Adventist Church’s ministry to them is the Huichol Flying Clinic, a Cessna 206 with which Pastor Cirilo delivers medical and spiritual care, and takes to the hospital those who are seriously ill.

Seventh-day Adventists have been reaching out to the Huichol for more than 50 years. Because Huichol territory is so remote, they can be reached only by air. The heart of the Adventist Church’s ministry to them is the Huichol Flying Clinic, a Cessna 206 with which Pastor Cirilo delivers medical and spiritual care, and takes to the hospital those who are seriously ill. When Cirilo reported these events to the Mexican authorities, they temporarily halted the tribe’s proceedings against the Christians. But threats continued. Cirilo was falsely accused of destroying Huichol shrines. Others tried to create trouble for the Christians by planting marijuana, a common but illegal crop, on their land. Some Christians found valuable livestock killed. School authorities discriminated against Christian students, and tribal authorities refused them government benefits and food.

When Cirilo reported these events to the Mexican authorities, they temporarily halted the tribe’s proceedings against the Christians. But threats continued. Cirilo was falsely accused of destroying Huichol shrines. Others tried to create trouble for the Christians by planting marijuana, a common but illegal crop, on their land. Some Christians found valuable livestock killed. School authorities discriminated against Christian students, and tribal authorities refused them government benefits and food.